| The

seventh century A. D. is considered as a landmark in the history

of Buddhism in Tibet. Through the introduction of Buddhism into

the land it witnessed a social and cultural advance. From the

seventh century onwards while extensive literary activity in

terms of translation from Sanskrit to Tibetan and composition

of Tibetan literature was in progress, a corresponding development

in art also took place. Many beautiful monasteries and temples

decorated with frescos and paintings, cast images and ritual

objects, were set up.

Tibet

in those days was open to foreign influences. It had continuous

contact with India, Nepal, China and the countries of Central

Asia, and hence was well disposed to receive all forms of art

and culture.

Hence,

there can be no doubt that the first artists who painted frescos

and modelled the figures of gods and goddesses of the Tibetan

Buddhist pantheon, were not Tibetan, but Indians, Nepalese and

Chinese. This is indicated by the account given of the construction

of the monastery bSam-yas according to which the lower part

was done in the Tibetan manner, the middle with a Chinese roof

and the upper part with an Indian roof. The same tradition also

claims that a castle built south-east of bSam-yas had nine turrets

and three floors: the ground floor, Tibetan; the two-roofed

first floor was built in the style of Khotan, the second in

Chinese style and the third in the Indian style.1

Foremost

among this influx of artistic culture from abroad was the importation

of art forms and styles from India. From the seventh century

onwards for several hundred years, cultural relations between

India and Tibet were at their peak. It was during these centuries

that countless Buddhist monks and their associates, including

artists and craftsmen, must have gone to Tibet and Nepal carrying

manuscripts, paintings and small portable icons in metal and

stone. These images and paintings probably served to illustrate

the preaching of the Dharma and they constituted the most important

examples of Buddhist iconography. Moreover, the images and the

illustrative materials served as models and inspiration for

the artistic development in the country. On the other hand,

many enthusiastic Tibetan monks undertook strenuous journeys

to India in search of knowledge in the field of religion as

well as in other secular subjects like medicine, logic, grammar,

astrology, and art. In the course of time, they mastered Buddhist

art, went back to their homeland to apply their newly acquired

knowledge in the field of art.

The

Indian styles which had a profound influence upon the early

development of Tibetan Buddhist art, were notably those of Gandhara,

Kashmir and Bengal. The styles of Gandhara and Kashmir distinguished

by Hellenistic motifs such as the Corinthian type of pillar

capital, the frequent occurrence of the Midas theme and the

use of elaborate floral and other motifs for filling up empty

spaces in murals and frescos found ready acceptance in the school

of Gu-ge centred in the west of Tibet. Concrete evidence of

the movement of these stylistic elements from Kashmir to Tibet

is provided by the murals at Alchi in Ladakh which are said

to have been executed by artists who accompanied the translator

Rin-chen-bzan-po on his return to Tibet from Kashmir.2

The

Pala style of Bengal characterised by the lightness of figures

and delicacy of treatment found its way to Tibet via Nepal.

These stylistic elements along with the richly ornamented thrones

and halos characteristic of Nepalese art are common in the Beri

school which became prominent in southern Tibet.

In

the development of Tibetan art, Nepal played a significant role.

Nepal acted as a meeting place between India on the one hand

and Tibet and China on the other. Nepal, by accepting the art

and iconography of Indian Buddhism together with its theory

and technique, rendered a great service to the growth of Tibetan

Buddhist art. The matrimonial alliance between Tibet and Nepal

concluded in the seventh century brought these two countries

into close contact. The Nepalese princess is said to have brought

to Tibet the images of Aksobhya,

Maitreya

and Tara.3

The images and paintings of Nepal definitely served as a source

of inspiration which developed the conception of aesthetic beauty

in the minds of the Tibetans.

The

art of Nepal continued to play a role in Tibet even much later

through the activities of skilled Nepalese artists. At the instance

of Kublai Khan, a wonderful artist from Nepal skilled in both

stone and metallic executions, named Aniko, with his eighty

companions, were invited by the abbot of Sakya, Chos-gyal

Phags-pa, to erect a golden stupa in Tibet.4

It is said that Aniko with his assistants decorated the monasteries

of Tibet and China. The style of Aniko became the guideline

for the Imperial Chinese art. The Nepalese influence can be

traced in those Tibetan Buddhist icons and paintings in which

we notice an increasing hieratic stylization of forms. The figures

become more and more loaded with a profusion of jewellery and

ornamentation. The Pala art of Bengal continued to develop in

Nepal which in its turn contributed its stylized version to

the development of Tibetan Buddhist art.

Beside

this Indo-Nepalese influence from the South, Tibet was also

in touch with the countries of Central Asia including Chinese

Turkistan. The destruction of Buddhist communities in Central

Asia by the Muslims forced Buddhist monks to take shelter in

the monasteries of Tibet. The various protectors of the Dharma

with their warlike following all clad in armour and typical

Central Asian attire in Tibetan Buddhist art can be considered

an importation from the North.

The

first influence of Chinese art from the Tang period became evident

as the result of the friendly - relations with China sealed

by the wedding of Sron-btsan-sgam-po

with the Chinese princess.

When

the foundations of Tibetan Buddhist art were being created,

certain influences were left by the temporary Tibetan rule in

the ninth century over Chinese Turkistan and the oasis of Tunhuang

in Kansu province famous for its rock temples. Again, in the

seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Chinese art exercised

a considerable influence over Tibetan art causing sudden changes

in the old traditions mainly in painting and architecture. New

monasteries were founded and old ones renovated.5

The

Chinese element in Tibetan art can be seen in the openness of

backgrounds, the use of

landscapes and the figures of animals and the diagonal action

of the figures as well as in the use of delicate pastels.

The

primary symbols which are to be found in Tibetan Buddhist Tantric

iconography range from those of universal and archetypal character

to those which may be referred to a limited cultural context.

Among the former we may count such symbols as the union of male

and female so prevalent in Tantric iconography and the image

of the tree

of enlightenment. These symbols are clearly not restricted to

any particular culture and have appeared many times in a variety

of religious and literary contexts.

In

addition, there are numerous symbols which are drawn from the

Indian mythological heritage and which are adopted and modified

to express Tantric concepts. Among these, perhaps the most notable

are the Vajra and the Padma.

The

Vajra, initially well-known as the sceptre of Indra, expressed

his mastery over the world. It came to assume tremendous importance

in Tantric philosophy and symbolism. While the original symbolic

significance remained relevant, because the Vajra wielded by

Buddhist Tantric dieties may be taken as expressing their mastery

over the world of existence, the Vajra came to symbolize a great

deal more in Buddhist iconography. It seems the primary significance

of the Vajra in Buddhist Tantric thought is as a symbol of the

indestructible nature of the ultimate truth. In this sense,

the term Vajra is often explained as synonymous with emptiness

(sunyata) which is indestructible.6

The Vajra is said to be superior to all things in that while

it is capable of destroying anything with which it comes into

contact, it, like a diamond, remains unaffected. It may well

be that this explanation of the significance of the term Vajra

led to the employment of the term Vajrayana as designation of

Tantric Buddhism in general. The connection may become clearer

if it is recalled that through Tantric methodology situations

and emotions normally injurious to spiritual progress can be

appropriated and turned to a religious purpose without in any

way adversely affecting the Tantric practitioner. Again, in

other contexts such as when it is found in association with

the Vajraghanta as in the case of Vajra-sattva, the Vajra represents

skilful means, the active component of the ultimate attainment

of Buddhahood, while the Vajra-ghanta or bell represents wisdom. The

Vajra, initially well-known as the sceptre of Indra, expressed

his mastery over the world. It came to assume tremendous importance

in Tantric philosophy and symbolism. While the original symbolic

significance remained relevant, because the Vajra wielded by

Buddhist Tantric dieties may be taken as expressing their mastery

over the world of existence, the Vajra came to symbolize a great

deal more in Buddhist iconography. It seems the primary significance

of the Vajra in Buddhist Tantric thought is as a symbol of the

indestructible nature of the ultimate truth. In this sense,

the term Vajra is often explained as synonymous with emptiness

(sunyata) which is indestructible.6

The Vajra is said to be superior to all things in that while

it is capable of destroying anything with which it comes into

contact, it, like a diamond, remains unaffected. It may well

be that this explanation of the significance of the term Vajra

led to the employment of the term Vajrayana as designation of

Tantric Buddhism in general. The connection may become clearer

if it is recalled that through Tantric methodology situations

and emotions normally injurious to spiritual progress can be

appropriated and turned to a religious purpose without in any

way adversely affecting the Tantric practitioner. Again, in

other contexts such as when it is found in association with

the Vajraghanta as in the case of Vajra-sattva, the Vajra represents

skilful means, the active component of the ultimate attainment

of Buddhahood, while the Vajra-ghanta or bell represents wisdom.

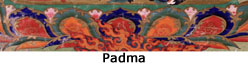

While

the significance of the Vajra underwent extensive development

and modification within the Buddhist Tantric  tradition,

the significance of the Padma or lotus seems to have remained

largely unaltered. The symbol of the Padma commonly found in

Indian spiritual iconography as representing the transformation

from an impure condition to a pure one which is the goal of

spiritual discipline, retained by and large the same significance

in Buddhist Tantric iconography. The Padma which is born in

the mud nonetheless rises above it and unfolds the flower of

spiritual excellence. The fact that nearly all Buddhist Tantric

deities of any consequence are pictured seated upon lotus thrones

indicates the purified condition of their being. tradition,

the significance of the Padma or lotus seems to have remained

largely unaltered. The symbol of the Padma commonly found in

Indian spiritual iconography as representing the transformation

from an impure condition to a pure one which is the goal of

spiritual discipline, retained by and large the same significance

in Buddhist Tantric iconography. The Padma which is born in

the mud nonetheless rises above it and unfolds the flower of

spiritual excellence. The fact that nearly all Buddhist Tantric

deities of any consequence are pictured seated upon lotus thrones

indicates the purified condition of their being.

Another

symbol which is often met with in both Mahayana and Tantric

iconography

is that of the sword or Vajra knife. The sword is best known

in Mahayana iconography as the weapon of the Bodhisattva Manjusri.

This Bodhisattva is usually pictured holding the sword in the

right hand and a holy text in the left. The sword is a symbol

of the wisdom of discrimination which cuts through the net of

erroneous views and ignorance while the text of the Perfection

of Wisdom represents the purified knowledge which replaces the

mistaken notions of the ego and the like which are responsible

for the presence of suffering. iconography

is that of the sword or Vajra knife. The sword is best known

in Mahayana iconography as the weapon of the Bodhisattva Manjusri.

This Bodhisattva is usually pictured holding the sword in the

right hand and a holy text in the left. The sword is a symbol

of the wisdom of discrimination which cuts through the net of

erroneous views and ignorance while the text of the Perfection

of Wisdom represents the purified knowledge which replaces the

mistaken notions of the ego and the like which are responsible

for the presence of suffering.

The

Vajra knife which is characteristic of Tantric iconography possesses

essentially the same significance as the sword. Such curved

knives are found wielded by large numbers of Tantric deities,

both major and minor. Vajrayogini holds such a knife as does

Mahakala in some representations.

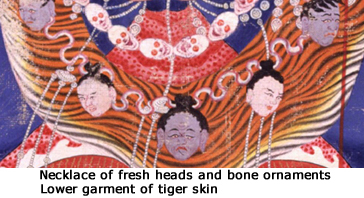

Moreover,

the many ornaments which adorn the figures of Tantric deities

have a wide range of significance ,

both general and specific. Professor Tucci has discussed exhaustively

the role played by the symbolism of royalty in Tantric iconography

as represented by the conception of the celestial mansion and

certain specific ornaments such as the crown which adorn the

head of Ratnasambhava.7 The

bone ornaments which are very striking features of Tantric iconography

as well as the garments of animal skins and the like can be

said to parallel the costumes of demons of Indian mythology.

Their assumption by the deities of the Buddhist Tantric pantheon

represents the defeat of the demonic forces by the Tantric deities.

Further, the symbolism of demonic costumes serves to reinforce

the Tantric conception that obstacles and passions may be transformed

and so used for spiritual ends. ,

both general and specific. Professor Tucci has discussed exhaustively

the role played by the symbolism of royalty in Tantric iconography

as represented by the conception of the celestial mansion and

certain specific ornaments such as the crown which adorn the

head of Ratnasambhava.7 The

bone ornaments which are very striking features of Tantric iconography

as well as the garments of animal skins and the like can be

said to parallel the costumes of demons of Indian mythology.

Their assumption by the deities of the Buddhist Tantric pantheon

represents the defeat of the demonic forces by the Tantric deities.

Further, the symbolism of demonic costumes serves to reinforce

the Tantric conception that obstacles and passions may be transformed

and so used for spiritual ends.

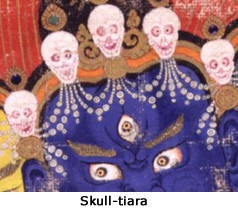

This

is not to say, however, that the complicated adornments which

decorate the figures of Tantric deities have only a general

and amorphous significance. They also admit of specific interpretations,

as expressing elements of Buddhist and Tantric philosophy. While

skull cups and ornaments of bone obviously express the consciousness

of impermanence which is so fundamental to Buddhist thought,

they have more specific references as well. For instance, the

crowns of five skulls which adorn the heads of a large number

of Tantric deities are explained in commentaries as representing

the five transcendent wisdoms 8

associated with the five Dhyani Buddhas. Again, the six

ornaments of bone, i.e.the skull-tiara, the armlets, the bracelets,

the anklets, the bone-bead apron This

is not to say, however, that the complicated adornments which

decorate the figures of Tantric deities have only a general

and amorphous significance. They also admit of specific interpretations,

as expressing elements of Buddhist and Tantric philosophy. While

skull cups and ornaments of bone obviously express the consciousness

of impermanence which is so fundamental to Buddhist thought,

they have more specific references as well. For instance, the

crowns of five skulls which adorn the heads of a large number

of Tantric deities are explained in commentaries as representing

the five transcendent wisdoms 8

associated with the five Dhyani Buddhas. Again, the six

ornaments of bone, i.e.the skull-tiara, the armlets, the bracelets,

the anklets, the bone-bead apron  and

waist-band combined with the double line of bone beads extending

over the shoulders onto the breast which adorn important Tantric

deities are explained as representations of the six perfections:

generosity, morality, patience, energy, concentration, and wisdom. and

waist-band combined with the double line of bone beads extending

over the shoulders onto the breast which adorn important Tantric

deities are explained as representations of the six perfections:

generosity, morality, patience, energy, concentration, and wisdom.

In

a survey of the symbols of Tantric iconography, one cannot overlook

the significance of the colours employed in thankas and murals.

Five primary colours are associated with the five Buddhas of

the basic mandala. Thus, they represent symbolically the quality

associated with each of the five Buddhas.

For

example, the Ratna family of Ratnasambhava

is associated with the element of earth and the defilement of

pride. The defilement of pride in its purified aspect takes

the form of transcendental wisdom of equality. The colour of

this family is yellow, the colour of earth. Yellow functions

as a symbol of putrescent pride while alternatively it symbolizes

the richness of gold which expresses the all-embracing equanimity

of transcendental wisdom.

The

Padma family of Amitabha

is associated with the defilement of passion and the element

of fire. In its impure state passion seeks to consume like fire

everything with which it comes into contact. In its purified

state, it is the transcendental wisdom of discrimination which

appreciates and apprehends precisely all situations with compassion.

The colour associated with this family is red. The brillance

and heat of red symbolizes passion which excludes everything

in its fascination with the object of desire. Alternatively,

the vividness and the brilliance of red symbolizes the all-embracing

compassion of the transcendental wisdom of discrimination.

In

addition, we find that many of the Tantric deities are black

in colour. Black symbolizes immutability, i.e. the quality of

remaining unaffected and impervious to any external influences.

Thus black symbolizes the inconquerable and secure nature of

the accomplished state.

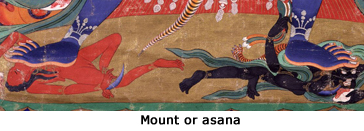

The

mounts or asanas upon which the Tantric deities are pictured

also have important philosophical  significance.

Thus it is that the corpse upon which Mahakala stands in some

representations is said to symbolize the ego and the triumph

of the deity over it. Yamantaka, the wrathful emanation of Manjusri

tramples upon the head of Yama which expresses his triumph over

death. Again, Vajrakila

is depicted trampling upon Siva and Uma who in this case symbolizes

his triumph over the extremes of eternalism and nihilism. significance.

Thus it is that the corpse upon which Mahakala stands in some

representations is said to symbolize the ego and the triumph

of the deity over it. Yamantaka, the wrathful emanation of Manjusri

tramples upon the head of Yama which expresses his triumph over

death. Again, Vajrakila

is depicted trampling upon Siva and Uma who in this case symbolizes

his triumph over the extremes of eternalism and nihilism.

The

objects which the various Tantric deities hold in their hands

also have specific significance. Vajrayogini,

for instance, holds in her right hand a vajra knife which symbolizes

the cutting off of naive ignorance. In her left hand, she holds

a skull cup filled with blood from which she drinks. This symbolizes

her consumption of the defilements which give rise to suffering.

Thus

the detailed description of the Tantric deities including colour,

ornaments, hand objects and mount found in the appropriate texts

and represented in paintings and images is capable of individual

and specific interpretation of all its elements. Therefore,

it is evident that the intricate symbolism of Buddhist Tantric

iconography includes a wide variety of symbols drawn from a

number of sources. The interpretations of the significance of

Tantric symbolism is all the more difficult, because the symbols

may be interpreted on a variety of levels which makes it impossible

to fix upon any one interpretation as exclusively correct. Nonetheless,

far from being a haphazard conglomeration of horrific forms

and macabre paraphernalia, Tantric iconography is a carefully

constructed system of psychological symbolism calculated to

express succinctly and pictorially the whole of Buddhist religion

and Tantric philosophy. It functions as skilful means by which

the Tantric adept is assisted in his appropriation and realization

of the divine vision. Thus, Tantric iconography is an integral

part of the process of liberation and enlightenment.

NOTES

1.

Steine, R. A., Tibetan Civilization, London, 1972, p. 283. [back]

2.

Gu-ge-Khri-tan ye-ses-dpal, Collected Biographical Material

About Lo-chen-Rin-chen-bzari-po and his Subsequent Reembodiments,

pp. 51 - 128. [back]

3.

Obermiller, E., History of Buddhism, Heidelberg 1931, p. 184

and Chattopadhyaya, A., Atisa and Tibet, Calcutta, India, 1967,

p. 186. [back]

4.

Ray, A., Art of Nepal, New Delhi, India, 1973. p.9. [back]

5.

Jisl, Lumir, Tibetan Art, p. 12. [back]

6.

Bhattacharyya, B., An Introduction -to Indian Buddhist Iconography,

Calcutta, India, 1968, Introduction. [back]

7.

Tucci, G., Theory and Practice of the Mandala, Roma, 1949, pp.

44 - 45. [back]

8.

Ibid., p. 70. [back]

-----by

the Same Author

1) The

Vajrayana: Myth and Symbolism

2) The

Tree of Enlightenment: An Introduction to the Major Traditions

of Buddhism

|