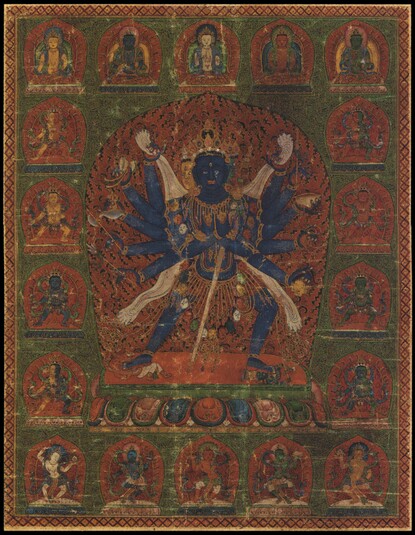

Item: Chakrasamvara (Buddhist Deity) - (Ghantapada Tradition)

| Origin Location | China |

|---|---|

| Date Range | 1500 - 1599 |

| Lineages | Buddhist |

| Material | Ground Mineral Pigment on Cotton |

| Collection | Private |

Classification: Deity

Appearance: Semi-Peaceful

Gender: Male

Chakrasamvara with four faces, twelve hands, and two legs. This depiction of the deity is solitary and does not present the red coloured consort Vajrayogini.

Based on the colour and placement of the faces this form of Chakrasamvara is identified as belonging to the mahasiddha Ghantapa Tradition. However, this cannot be taken as definitive as there are so many different colour configurations for the four faces of Chakrasamvara. (See Chakrasamvara Four Faces).

Standing on either side of the central figure are two vertical rows of four dakini retinue deities. Four figures have two-toned coloured bodies and occupy the intermediate directions of the of the outer corners of the palace of the mandala of Chakrasamvara: Yamadahi, Yamadhuti, Yamadamstri, and Yamamathani. The colours are yellow-red, red-green, blue-green, and yellow-blue. The colors relate to the four directions: east blue, south yellow, west red and north green.

The remaining four figures form the inner circle of deities of the mandala have bodies of solid colours: blue Dakini, green Lama, red Khandarohe, and yellow Rupini. The colours instruct and determine their placement in the mandala.

The form, colours and ornamentation of the figures in the composition follow an Indian Tantric Buddhist iconographic program. The background elements, floral and vine work designs follow a Tibetan borrowing of Nepalese stylized paintings. It is worth noting that Chinese Buddhist paintings from this general time period do not provide a lot of distinction between male and female forms.

"...Shri Chakrasamvara with a body blue in colour, four faces and twelve hands. The main face is blue, left face red, back face yellow and right face white. Each face has three eyes and four bared fangs. The first two hands hold a vajra and bell embracing the mother. The lower two hold an elephant skin out-stretched; third right a damaru, fourth an axe, fifth a trident, sixth a curved knife. The third left holds a katvanga marked with a vajra; fourth a vajra lasso, fifth a blood filled skullcup, sixth carries the four-faced head of Brahma. The right leg is straight and presses on the breast of red Kalaratri; left bent and pressing on the head of black Yama. The hair is tied in a topknot on the crown of the head; on the crest a wish-fulfilling jewel ornament and crescent moon. The soft spot at the top of the head is marked with a vishvavajra. Each head has a crown of five dry human skulls; a necklace of fifty fresh heads and six bone ornaments; wearing a lower garment of tiger skin; possessed of the nine emotions of dancing; grace, fearlessness and ugliness; laughter, ferocity and frightfulness; compassion, fury and peacefulness." (Written by Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo (1820-1892). The Collected Works of the Great Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo, vol.7, fol.215-226. Gyud de Kun Tus, vol.25, folios 11-19. [Translated October 14, 1989]).

Chakrasamvara Lineage, Abisheka, Root Tantra and Commentary: Vajradhara, Vajrapani, Maha Brahmin Saraha, Acharya Nagarjuna, The Protector Shavari, Luipa, Darikapa, Vajra Ghantapa, Kumarapada, Jalandharapa, Krishnacharya, Guhyapa, Nampar Gyalwai Shap, The Acharya Barmai Lobpon, Tilopa, Naropa, Pamtingpa Kuche Nyi, Lama Lokkya Sherab Tseg, Lama Mal Lotsawa, The Lord of Dharma Sakyapa (Sachen Kunga Nyingpo 1092-1158).

The Gantapada Lineage of Three Cycles, together with its Branches: Vajradhara, Vajravarahi, Vajra Ghantapada, (etc., continuing from Ghantapa in the previous lineage).

At the top of the composition, starting at the left side, are the Five Symbolic Buddhas: yellow Ratnasambhava, blue Akshobhya, white Vairochana, red Amitabha and green Amoghasiddhi. At the bottom of the composition are the five Offering Goddesses of the senses: sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch.

Jeff Watt 8-2020

Chakrasamvara by Laura A. Weinstein. July, 2020

Chakrasamvara is depicted here as described in Sanskrit and Tibetan ritual texts, with a “blue-black” body, an additional three heads of red, green and yellow to see in each direction, and twelve arms, each bearing its own tantric implement. The symbolism behind Chakrasamvara’s iconography is manifold: his vajra and bell symbolize his mastery of method and wisdom; his elephant hide represents the destruction of illusion; his damaru and khatvanga represent the aspiration for enlightenment; his curved knife and skull cup symbolize utter egolessness; he cuts off the six defects with his ax and harnesses wisdom with his lasso; his trident marks his triumph over the threefold world; and, finally, the severed head of Brahma hanging from his lower right hand represents his supreme wisdom, penetrating all worldly illusions. He tramples Bhairava and Kalarati beneath his right and left feet, respectively, demonstrating his higher status than the Hindu gods.

In the context of Tibetan Buddhism, Chakrasamvara, Korlo Demchog (Tibetan), or ‘Wheel of Bliss’, arises out of Tibetan translations of a fifty-one chapter root tantra and several explanatory tantras with Sanskrit originals. The Chakrasamvara Tantra is the principal tantra of the Anuttarayoga or ‘Unexcelled Yoga’ classification of the Vajrayana Buddhist tradition, providing the greatest detail on how to experience the four stages of bliss within the central channel of the body. Visualizations of Chakrasamvara can ultimately enable one to reach the most subtle level of mental activity and, eventually, to enlightenment. Chakrasamvara is depicted here without his consort, Vajrayogini, which is quite unusual. However, it is not this detail, but rather the arrangement of his four faces that tell us this form likely belongs to the mahasiddha Ghantapa’s tradition, as the meditations and rituals he passed forward describes the four colored-heads as depicted in the present painting. The eight dakini retinue figures that occupy the vertical space on either side of the central figure are common to all Chakrasamvara traditions but are notably depicted with two arms rather than four here--another mark of its connection to the Ghantapa tradition. The solid-colored dakini occupy the main cardinal directions surrounding the Chakrasamvara at the center of the mandala while the dual-colored dakini occupy the intermediate directions. They can be identified in clockwise fashion as Yamadhuti, Khandarohe, Lama, Yamadamstri, Yamamathani, Dakini, Rupini, and Yamadahi. At the bottom of the composition are the Five Offering Goddesses of the senses: sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch. Yellow Ratnasambahva of the South, blue Akshobhya of the East, white Vairochana of the central direction, red Amitabha of the West, and green Amoghasiddhi of the North float on lotus thrones along the top register.

Twentieth-century scholarship might lead one to catalogue this painting as Nepalese for the employment of registers, its copious use of the vegetal scrollwork motif, and the deep jewel-toned color palette dominated by red. In a way, the present painting is actually a continuation of the Nepalo-Chinese style of the Yuan period (1279-1368) which began with an important connection formed at the imperial court between the renowned Kathmandu-Valley artist Anige and the Tibetan Sakya lama Phakpa Lodro Gyeltsen (1235-1280) who served as Kublai Khan’s first Imperial Preceptor. The present painting gives away its Chinese origin, however, in its presentation of female retinue figures as genderless and by omitting Chakrasamvara’s consort with whom he is traditionally depicted in sexual embrace. Such is representative of Chinese court sensibilities about Tantra.

When this painting was previously sold in 2001 it was accurately described as representative of the culmination of the Tibeto-Chinese style in the second half of the fifteenth century. The first Ming Emperor, Taizu, pledged to continue imperial patronage of and engagement with Tibetan Buddhism in order to maintain political legitimacy with the ruling Chinggisid surrounding the Ming Empire after the fall of the Yuan. Ming Emperor Yongle made this relationship even more central to his rule, marking the height of Tibetan Buddhist patronage during the Ming period. While successive emperors continued this relationship, Emperor Chengua (r. 1465-1487), once again, placed a more notable emphasis on patronizing the tradition and the present painting is a product of that period.

In 2001 the present painting was, however, inaccurately described as “likely originated from the Da longshan huguo si monastery in northwest Beijing.” At the time of the sale, three Zhengde-period paintings were repeatedly used by scholars as the key for identifying the provenance of the Chenghua group of which the present painting is a part. The key Zhengde-period thangka is a painting of Simhamukha published in Tucci’s Painted Scrolls (1949, pl. 205), which names a “Da Huguo” monastery and a patron “Daqing Fawang Rinchen Palden”, which Hugh Richardson was able to identify as Emperor Zhengde’s Tibetan Buddhist name.

The many stylistic similarities between Tucci’s Zhengde-period Simhamukha and an associated group (see Marsha Weidner, “Beyond Yongle: Tibeto-Chinese Thangkas for the Mid-Ming Court” for the other Zhengde examples) with the present painting explain this earlier association with Da Huguo Monastery. Like the Zhengde-period Simhamukha, the present Chenghua-period Chakrasamvara as well as a Chenghua-period Simhamukha and a Four-armed Mahakala at the Victoria and Albert Museum (IS.14-1969 and IS.15-1969) share a deep palette of red, green, and blue, highly ornate decorative patterns that fill the backgrounds, and a painted red border patterned with gold visvavajra or crossed dorje symbols enclosed in black-outlined rhombuses, imitating brocade. The inscriptions on all of these paintings lie within these lozenges on the bottom register of the composition, with one character within each lozenge.

The inscription on the present painting, however, differs from that of the Tucci thangka as well as other Zhengde-period examples in its content and in that it reads right to left (as do the other Chenghua-period paintings mentioned above). This painting is dated to the 2nd day of the 11th month of the 13th year of Chenghua (1477 AD)--the Emperor Chenghua’s birthday. The V&A Simhamukha (IS.14-1969) bears the same date as does a painting of the same style depicting Hevajra at the Musee Guimet, just three years earlier. Thus, we know that these thangkas were commissioned for ceremonial use surrounding Emperor Chenghua’s birthday and were almost certainly made in a court workshop. Where they hung, however, is entirely speculation.

Exhibited:

“The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art”, Los Angeles County Museum of Art: October 05, 2003–January 04, 2004; Columbus Museum of Art: February 06–May 09, 2004.

Literature:

“The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art,” online at https://huntingtonarchive.org/Exhibitions/circleOfBlissExhibit.php, no. 83.

Marsha Weidner, “Beyond Yongle: Tibeto-Chinese Thangkas for the Mid-Ming Court,” Artibus Asiae, vol. 69, no. 1, 2009, pp. 7–37, fig. 14.

Himalayan Art Resources, himalayanart.org, item no. 20645

Buddhist Deity: Chakrasamvara Main Page

Painting Style: Ming Period Style (1368 to 1644)

Buddhist Deity: Chakrasamvara (Mandala Deity Assembly)

Collection: Christie's, New York (Painting & Sculpture. 2020)

Collection: Christie's, New York (Painting & Sculpture. September, 2020)

Buddhist Deity: Chakrasamvara (Early Figurative Painting)

Collection: Christie's, Painting (Sept, 2001; NY)

Buddhist Deity: Chakrasamvara (Solitary Complex)