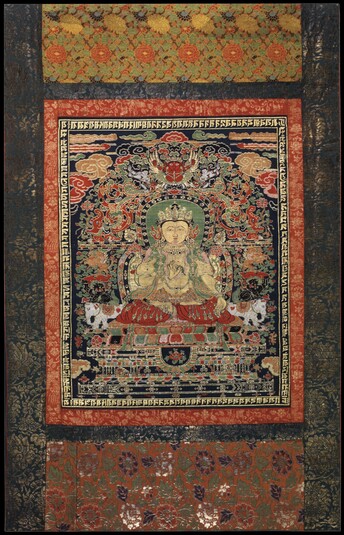

Item: Avalokiteshvara (Bodhisattva & Buddhist Deity) - Bodhisattva

| Origin Location | China |

|---|---|

| Date Range | 1400 - 1499 |

| Lineages | Gelug and Buddhist |

| Size | 72.40x57.10cm (28.50x22.48in) |

| Material | Ground: Textile Image, Kesi |

| Collection | Private |

Alternate Names: Lokeshvara Avalokita Lokanata Lokanatha Mahakarunika

Classification: Deity

Appearance: Peaceful

Gender: Male

Avalokiteshvara with one face and two arms seated in vajra posture - a tentative identification. (Note: this is a reversed weaving).

The identification of this textile representation as Avalokita is based on similar sculptural examples of the deity along with the elimination of other popular figures such as Maitreya, Manjushri or Vajrapani. The issue of identification arises because of the lack of any attributes accompanying the figure as well as not having any inscriptions other than the Lantsa script dharani decorating the four sides of the composition. The textile is a rare example of a reversed weaving. Typically objects such as this would be destroyed at the time of discovering the mistake. (See Avalokiteshvara Vajra Posture Sculpture).

Best Examples: - Yongle Period: HAR #10596 - Kangxi Period: HAR #3256

Throne Back Elements (Torana): - Garuda - Nagas - Makaras - Sharabhas - Lions - Elephants

Jeff Watt 8-2023

The bodhisattva is shown seated in dhyanasana on a multitiered lotus throne with right hand in vitarkamudra and left hand in varadamudra, both holding the stems of large lotus flowers that flank the shoulders. The figure wears a long green shawl draped over the shoulders and arms, a red dhoti secured by a jeweled tassel-hung girdle at the hips, as well as other jewelry, including necklaces, large earrings and a five-point crown. The figure is backed by an aureole surrounded by foliate scroll incorporating white elephants, lions, qilin, makaras and apsaras flanking a Garuda at the top below multicolored clouds, all within an outer border of a continuous Lantsa inscription in gold. The thangka is finely woven in rich shades of red, orange, yellow, green, pink, white and black, with outlines and highlights in brilliant gold against a deep blue ground. The thangka is surrounded by borders of Ming and Qing date.

Thangka 28½ x 22½ in. (72.4 x 57.1 cm.)

The result of RCD Radio Carbon Dating test number RCD-6767 is consistent with the dating of this lot.

Christie's Catalogue Entry, 3-2014

AN IMPORTANT IMPERIAL SILK BROCADE THANGKA OF PADMAPANI

This sumptuous textile is a masterly example of complex drawloom weaving that arose as a technique during the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) and continued into the very early Ming dynasty period of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The supplemental weft-patterned satin features brocaded colored silk and gold-leaf-on-paper strip designs on a navy blue ground. It is in near mint condition. Thus, we are afforded a rare glimpse of the dazzling effect of early Ming luxury fabrics for religious use.

Four other examples of this design are known: one in the collection of the Hong Kong Museum of Art (1), two in the Chris Hall Collection Trust (2) and a fourth in a private collection in the United Kingdom (3). All share the same loom tie up that has produced identical minor errors in some of the gold-leaf-on-paper strip details, particularly noticeable just inside the Lantsa script borders along each side. The width dimension of these thangkas is within a centimeter and a half of each other, suggesting all are from the same warp and are a product of a unique drawloom tie up. A related thangka with a different primary image, but with identical borders, aureole and background, and worked only in gold-leaf-on-paper strip, shares the same loom width. This example is also in the Hong Kong Museum of Art Collection.(4)

One of the more interesting aspects of the Padmapani group has to do with the manner in which they were produced. Two of the images, including the current example, are mirror images of the other three. This resulted when the weaver reversed the draw order controlling the pattern warps as the weaving progressed in the vertical direction along the entire length of the warp. The weaver started weaving from the bottom of the image and when he completed the top he adopted a time-saving maneuver not to have to re-sort all of the pattern pulling cords. Rather, he simply reversed the call order of raising the pattern warps and proceeded to weave from the top of the image to the bottom only to repeat the process. The resulting alternate images are themselves reversed. From unit to unit there have been color changes for some elements of the design, including icon figures, haloes, flowers and elements of the throne.

The configuration of varada (giving) mudra for the hand of the extended arm and the hand of the flexed arm in vitarka (teaching) mudra are proscribed for images of Padmapani. Both hold a trailing stem of the full-blown lotuses that are displayed at either shoulder. Although variation can be documented on sculpture and some paintings, the arrangement in this thangka is essentially backwards iconographically. The Lantsa script, on the other hand, becomes unreadable. This eleventh-century script developed for writing the Newari language in Nepal was used in Tibet for some original texts in Sanskrit, but more often decoratively as headers or on objects employed in worship. It was not universally intelligible and may not have been seen as a problem for the recipients of these splendid fabrics.

Iconographic errors abound in woven Buddhist representations dating from the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. Previously, such images had been painted or printed. As those images moved into the realm of textile production, non-Buddhists would not necessarily have recognized the proscribed attributes for figures that were immediately apparent to Buddhist initiates. It is likely that some of the weaving families responsible for these luxury textiles were descendants of the accomplished weavers and goldsmiths forcibly relocated from Muslim western Central Asia by the khans of the Yuan dynasty. Some members of these weaving families, who settled in Beijing and Sichuan, may have remained Muslim. However, by the early fifteenth century the ateliers producing luxury textiles for the imperial court were managed by exacting supervisors. As a result, we see only perfectly realized Buddhist textiles, such as the monumental, brocaded satin Mahakala thangka with a six-character Yongle mark woven into the design (5). It should be noted that all the very best quality Yuan-dynasty thangkas were woven in silk tapestry, or kesi technique, which made it easier for a weaver to control the rendering of complex images as he copied a picture supported behind the warp. During the early Ming period kesi weaving was actually forbidden, resulting in the reversion to time-honored methods of brocade and embroidery.

The practice of outlining each design element of a textile design in gold, a technique that developed during the Tang dynasty (618-907) and continued until the end of dynastic China, has the effect of making the color pop off the ground, adding to the sumptuous effect the designer of this pattern intended. It was a favored feature of textiles made for imperial use or for imperial gifts. The color scheme on this thangka largely continues to honor the classical Chinese use of five colors for imperial textiles. Red, white, black, blue/green and yellow, represented the wuxing, or five elements that categorize the directions and planets, as well as phases of creation and decay. In the Padmapani thangka we see some additional tones of pink, orange and light blue on some of the clouds and details of the aureole and throne. Shading in several tones of a color would become a hallmark of imperial textiles during the Yongle period (1403-1425).

Historical information, as well as the technical and stylistic characteristics of this Padmapani thangka, reinforces the radiocarbon test data that support a late fourteenth-century date. Such a complex weaving, with such an emphasis on the lavish use of gold, indicates it was the product of imperial workshops, probably made as a diplomatic gift to Tibet. The technical challenges of producing large scale Buddhist figural drawloom weaving were not overcome until the fifteenth century, when the Yongle Emperor, a fanatical Buddhist, demanded uncompromised perfection from imperial weaving ateliers. The transition of such ateliers from Yuan imperial control to Ming control, after 1368, may have contributed to the production challenges of this group of Padmapani thangkas.

John E. Vollmer, New York, 2 February 2014

(1) Hong Kong, Oriental Ceramic Society of Hong Kong, Liaoning Sheng bo wu guan, and Hong Kong Museum of Art. 1995. Heavens' embroidered cloths: one-thousand years of Chinese textiles. Hong Kong: The Council. No. #28, accession no. C1993.0018, pp. 136-37.

(2) Ibid. No. 30, pp. 140-41. Christie' New York, Fine Chinese Ceramics, Bronzes, and Works of Art, 25 March 1998, lot 418 "A Rare Silk Brocade Thangka of Tathagata Ratnasambhava [sic]."

(3) Offered by A&J Speelman, London, www.ajspeelman.co.uk/details.php?sid=167

(4) Hong Kong, Oriental Ceramic Society of Hong Kong, Liaoning Sheng bo wu guan, and Hong Kong Museum of Art. 1995. Heavens' embroidered cloths: one-thousand years of Chinese textiles. Hong Kong: The Council. No. #29, accession no. C1993.0020, pp. 138-39.

(5) Ibid., No. 26, pp. 132 - 33; Christie's New York, Fine Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art, 29 March 2006, lot 275, "A Very Rare and Exceptionally Large Imperial Silk Brocade Thangka."

Collection of Zhiguan (Painting & Textile)

Collection: Christie's, Painting (March, 2014; NY)

Textile: Early Ming Woven Set

Textile: Main Page

Buddhist Deity: Maitreya Main Page

Textile: Woven Artwork Main Page

Buddhist Deity: Maitreya Bodhisattva (Seated)