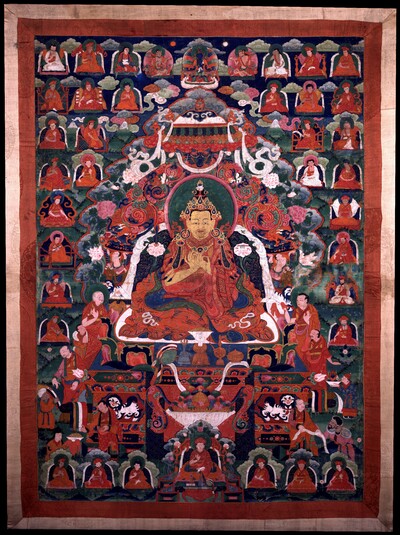

Item: Teacher (Lama) - Gotsangpa Gonpo Dorje

| Origin Location | Bhutan |

|---|---|

| Date Range | 1800 - 1899 |

| Lineages | Drukpa (Kagyu, Bhutan) |

| Material | Ground Mineral Pigment on Cotton |

| Collection | Rubin Museum of Art |

Classification: Person

TBRC: bdr:P2090

Gotsangpa Gonpo Dorje (1189-1258).

Gotsangpa Gonpo Dorje (1189-1258)

Centuries before Shakespeare wrote As You Like It with those famous words "All the world's a stage," Gotsangpa "transformed all phenomenal appearances into music" (snang ba rol mor bsgyur). From the very beginning he was fond of music and dance. His middle teens he lived as the kind of performance artist known in those days as a pagshi (pag shi). Carrying oiled red scepters and wearing 'bird-horn' (bya ru) hats that looked rather like Viking helmets or, perhaps more to the point, jesters' caps, his company would tour the countryside performing instrumental music, songs and dances in the open areas of villages and towns. A handsome and gifted young man, when he performed people would forget all their problems, and not just human beings. Even inhabitants of the spirit worlds would be drawn into the audience against their will.

In those days he was known by his stage name Dondrub Sengge (don grub seng ge). People were so impressed they said he must have been a god in his previous life. As a teenager he was known as Pagshi Dondrup Sengge (pag shi don grub seng ge). In pre-Mongol times pagshi meant a traveling performer, which might involve acting, juggling, acrobatics, story telling, dancing and singing. In the later Mongol Empire the same word, usually written bakshi, would come to mean a religious teacher.

As we know, the life of the star performer is not always without its problems. Living in Lhodrag (lho brag) in southernmost Tibet, by the time his mother gave birth to him, both of his older siblings had already died. His childhood name was Gonpo Pal (mgon po dpal). As a young child his parents separated in a dispute about their shrinking finances. His mother eloped with a wealthy doctor and left him under his father's care. With only thirty goats and sheep, and fields that refused to yield a good harvest, his father contracted a 'dark phlegm' disease that made him vomit blood, and soon after that he died. For some time the young boy was able to earn his own way as a reader. Payment for such services usually meant little more than a meal. A few years later, at age ten, he was able to visit his estranged mother. She sprang on him the revelation that he was not in fact his father's child, but the child of the doctor she had married. This might have been just a white lie because she wanted to persuade him to come and help out with the chores around the house. Anyway, he rejected his mother's story and refused to accept a newly discovered biological father.

By the age of sixteen, in part inspired by devotional activities he witnessed during his visits to Lhasa, Gotsangpa felt an aversion to worldly affairs along with a desire to study Buddhism. He studied texts and received teachings from a number of teachers, primarily in the traditions of Kadam, Shije and Kagyu. Not certain which one he would follow, he received his answer in a dream, and then heard a minstrel of Tsang Province sing these words:

In Ralung Monastery is the one name Tsangpa Gyarepa. He holds the key to happiness in this life and the next. Shall we two friends go to him or not? Shall we go to him for teachings from the heart or not?

The words of the song opened Gotsangpa's eyes and inspired a deep veneration. When he reached Ralung (rwa lung) he was almost immediately received by Tsangpa Gyarepa who greeted him with a smile and said, "So have you made your appearance then? Splendid!" That same year he took novice vows along with the new name Gonpo Dorje (mgon po rdo rje), the same name as the famous hunter converted by Milarepa.

Once during his first months in Ralung a mouse chewed up his flour sack and his robe. His first response was to curse the mouse, but he soon composed his thoughts and reflected that, according to the Hinayana, we ought to practice non-harm, according to the Mahayana we ought to consider all beings as our mothers, and according to Vajrayana each being has to be seen as the divine form of high aspiration, the yidam. This perspective would hold him in good stead during the coming years of solitary meditation in remote places, where he excelled in withstanding extreme discomfort and sickness. He refused to accept obstacles as obstacles. While staying at Ralung his chief delight was to drink in all of Tsangpa Gyarepa's teachings, from the most exoteric to the most secret. Although the teacher-disciple relationship has often seemed a stormy one in Kagyu history, in their case there was never a single word of disagreement, scolding or complaint. When he wanted to go and study with other teachers, particularly at Drigung, he went with his teacher's blessing, given without hesitation.

When Tsangpa Gyarepa died, Gotsangpa resolved to fulfill the words of his teacher's last will and testament, which said simply, "Give up concerns of the present life. Stay in mountain retreats." After three years of meditation in Kharchu (mkhar chu) where Tsangpa Gyarepa had once meditated, he was inspired to visit Mt. Kailash (ti se) in part because of its association with Milarepa. But at the same time, age twenty-five, he was thinking about going to Jalandhara, a city now in Himachal Pradesh. Although it is today a rather small town, not far from Dharamsala where the Dalai Lama resides in exile, it was once an important center for Buddhists, Hindus and Jains. It was the site of the Third Council held by Kanishka according to Buddhist history. Gotsangpa went there because it is one of the twety-four Places of the Vajra Body of Heruka listed in Cakrasamvara Tantras. Tibetans believe that two of them are actually located in Tibet, at Mt. Kailash in western Tibet, and Tsari in the east, although of course most of them are in India.

Well into his journey, in Lahaul (gar zha), he met a Tibetan translator named Gar Lotsawa (mgar lo tsA ba) and told him of his plan to visit Jalandhara.

Gar Lotsawa dismissed the idea, "You won't reach it. Food is hard to get. You don't know the language. The road is infested with death-happy bandits. On the one-in-an-hundred chance you do make it there, you will be blocked by the non-human spirits in the cemeteries."

But Gotsangpa was so determined to go that Gar decided to go with him, which at least solved the problem of not knowing the language. The passes that both join and separate Lahaul and Chamba would have proven impassible if it were not for the good fortune of meeting some local porters he called Monpas (mon pa). With pickaxes and ropes tied around their waists they helped them by making footholds in the mirror-smooth rock faces. Gotsangpa said about these Monpas that they had nothing to wear but deerskins and nothing to eat but buckwheat chaff. Meanwhile the two Tibetans had nothing at all to eat and were constantly passing out from hunger. After a twelve-day trek, thrilled to see just how green forests can be, and catching a first glimpse of the Indian plains "as smooth as the palm of the hand" stretching out beneath them, they found themselves in the capital of the Chamba king.

Gar sat himself down inside the fort and started playing his double-headed drum called the damaru, which brought the whole fort and village out to have a look at the curious strangers. Even the king, who was evidently a Muslim, came out on his veranda and called out in Persian, "Pir! Pir!" the word used for Sufi masters, although it literally means 'elder.' Several days later, when they reached Jalandhara, the people must have been mainly Hindu, since they shouted out "Guru! Guru!" After visiting the temple of Jwalamukhi (the name means 'Flaming Mouth'), which is still today famous for its eternal flames emerging from the rock, they came to the town of Jalandhara itself.

Jalandhara is one of the twenty-four Places of the Vajra Body, according to the Cakrasamvara system. As an external pilgrimage spot for yogis it corresponds to a part of the inner Vajra Body made up of channels and drops, what is known as the 'Body Mandala.' Because they were practicing Completion Stage yogas, they experienced the Holy Place through a constant buzz of inner meditative experiences. Their bliss was so great they scarcely noticed when some of the town people cursed the strange foreigners, or when the children showered them with dirt clods. But the temple and town were not the main goal of their visit. There were five cemeteries in the area where they intended to meditate. During their months of meditation they survived like the other religious mendicants by once a day visiting doorsteps in the villages just after the women had finished preparing the morning rice. Hearing the damarus the women would come and place a mouthful worth of rice inside each of their gourd begging bowls. But the village women were not always willing to give food to the foreign yogis, and in any case the food was not what Tibetans were accustomed to eating. Eventually they returned to Lahaul by way of Kulu Valley, and yet another Place of the Vajra Body called Kuluta. Back in a Buddhist land, they received offerings of new monastic robes, recovered from their illnesses, and spent the summer meditating at Mt. Gondhola, a place still associated with Gotsangpa's name in the minds of modern Lahaulis.

After returning to Ralung, Onre Darma Sengge, who was then the abbot, advised him to meditate at Pom Lhakhab (phom lha khab), so he went to practice there for three years in a hut. Once the nearby lake overflowed and flooded his hut, but he remained in meditation with his body half submerged, living on nothing but water. It was only then that he took complete ordination from the abbot of Ralung. Later on he became quite well known for the devoted service he provided to the hermits in Tsari in the eastern part of Tibet, inside the great bend of the Tsangpo River. To support the meditating hermits in their scattered caves he carried roasted barley flour on his back until the blisters broke, which earned him the affectionate nickname, Yellow Donkey. Getting Onre's permission, he went to meditate at a place not far from the border with Nepal called Gotsang (rgod tshang), where he remained for seven years. It appears that by this time he had become quite famous, which is why he would forever after be known as Gotsangpa, 'the man of Gotsang.'

Gotsangpa spent the last years of his life founding a number of monasteries, initiating the tradition of the Drugpa Kagyu known as Upper Drug (stod 'brug). In each of the monasteries some thousands of practitioners gathered. Among his last instructions before his death, he requested that no dues be collected among his followers and that rather than collecting offerings for constructing images and the like they should devote themselves to solitary meditation. Among his main disciples the best known are Yanggonpa (yang dgon pa), Orgyenpa Rinchen Pal (o rgyan pa rin chen dpal), Madunpa (ma bdun pa), and Bari Chilkarwa (ba ri spyil dkar ba).

Sources:

Roerich, George, trans. 1996. The Blue Annals. 2nd ed. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas, pp. 680-87.

Tucci, Giuseppe. 1971. "Travels of Tibetan Pilgrims in the Swat Valley." In Opera Minora. Rome: Giovanni Bardi, pp. 373-83.

See TBRC for a long list of Tibetan biographies of Gotsangpa

Dan Martin, 2009

[Extracted from the Treasury of Lives, Tibetan lineages website. Edited and formatted for inclusion on the Himalayan Art Resources website. November 2009].

Front of Painting

Wylie Transliteration of Inscription: rgyal ba rgod tshang ba mgon po rdo rje 'chang la na mo.

Subject: Black Hats & Blue Hats Main Page

Region: Bhutan, Main Page

Collection of Rubin Museum of Art (RMA): Main Page

Region: Bhutan, Paintings

Region: Bhutan, Teachers

Collection of Rubin Museum of Art: Bhutan

Exhibition: Big!

Subject: Lineage Composition (Greyscale)

Region: Bhutan: Painting & Textile Masterworks

Teacher: Gotsangpa Gonpo Dorje

Collection of RMA: Bhutan Masterworks

Biographical Details

Biographical Details