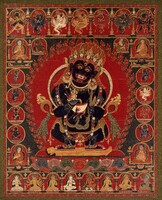

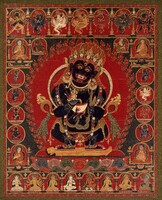

Panjaranata Mahakala is the protector for the Shri Hevajra cycle of Tantras. The iconography and rituals are found in the 18th chapter of the Vajra Panjara Tantra (canopy, or pavilion), a Sanskrit language text from India, and an exclusive 'explanatory tantra' to the Hevajra Tantra itself. It is from the name of this tantra that this specific form of Mahakala is known. 'Vajra Panjara' means the vajra enclosure, egg shaped, created from vajra scepters large and small - all sizes, completely surrounding a Tantric Buddhist mandala. The name of the Tantra is Vajra Panjara and the name of the form of Mahakala taught in this Tantra is also Vajra Panjara. The full name for the protector is Vajra Panjara Nata Mahakala.

Western scholars, such as Laurence Austine Waddell and Albert Grunwedel, in the 19th and early 20th century believed that the meaning of the name was 'tent' and that this Mahakala was a special protector of the Tibetan and Mongolian nomads who lived in tents. They even went so far as to say that the wooden staff held across the forearms of Panjarnata was a tent pole. The confusion for Western scholars arises from the fact that the early Tibetans translated the Sanskrit word 'panjara' with the Tibetan word 'gur'. The word 'gur' in Tibetan can mean tent, canopy, enclosure, dome, etc. This academically erroneous belief that Mahakala was 'of the tent' was however supported by Mongolian folk belief where they believed that Panjara Mahakala, originally introduced to Mongolia by Chogyal Pagpa in the 13th century, was indeed special for them based on the Chogyal Pagpa and Kublai Khan relationship. Panjara Mahakala was also popular for the Mongolian nobility and used as a war standard during the time of Kublai Khan.

Western scholars, such as Laurence Austine Waddell and Albert Grunwedel, in the 19th and early 20th century believed that the meaning of the name was 'tent' and that this Mahakala was a special protector of the Tibetan and Mongolian nomads who lived in tents. They even went so far as to say that the wooden staff held across the forearms of Panjarnata was a tent pole. The confusion for Western scholars arises from the fact that the early Tibetans translated the Sanskrit word 'panjara' with the Tibetan word 'gur'. The word 'gur' in Tibetan can mean tent, canopy, enclosure, dome, etc. This academically erroneous belief that Mahakala was 'of the tent' was however supported by Mongolian folk belief where they believed that Panjara Mahakala, originally introduced to Mongolia by Chogyal Pagpa in the 13th century, was indeed special for them based on the Chogyal Pagpa and Kublai Khan relationship. Panjara Mahakala was also popular for the Mongolian nobility and used as a war standard during the time of Kublai Khan.

The 'Vajra Pavilion' when represented in mandala paintings or for three-dimensional mandalas is known as the 'Vajra Circle' (Sanskrit: vajravali): inside of the outer ring of a two-dimensional mandala, painting or textile, is a circle of fire and then a vajra circle. This vajra circle is often difficult to see and easy to dismiss as simply decorative. The circle is a series of gold or yellow vajras, painted against a dark blue or black background, lined up end to end and circling around the entire mandala, deity and palace. The vajra circle is not envisioned as flat or horizontal like the lotus circle. The vajras are seen as a three dimensional pavilion, without doors or windows, completely enclosing the mandala. It is made entirely of vajras, small and large with all of the openings filled with ever smaller vajras. It is a three-dimensional structure and impenetrable. Envisioned as a three-dimensional object it is called the Vajra Pavilion and according to function it is called the Outer Protection Chakra.

The 'Vajra Pavilion' when represented in mandala paintings or for three-dimensional mandalas is known as the 'Vajra Circle' (Sanskrit: vajravali): inside of the outer ring of a two-dimensional mandala, painting or textile, is a circle of fire and then a vajra circle. This vajra circle is often difficult to see and easy to dismiss as simply decorative. The circle is a series of gold or yellow vajras, painted against a dark blue or black background, lined up end to end and circling around the entire mandala, deity and palace. The vajra circle is not envisioned as flat or horizontal like the lotus circle. The vajras are seen as a three dimensional pavilion, without doors or windows, completely enclosing the mandala. It is made entirely of vajras, small and large with all of the openings filled with ever smaller vajras. It is a three-dimensional structure and impenetrable. Envisioned as a three-dimensional object it is called the Vajra Pavilion and according to function it is called the Outer Protection Chakra.

Translating the Sanskrit word 'Panjara' as 'tent' is neither descriptive for Panjarnata Mahakala, accurate of the intended meaning, nor helpful in any way to understand this very important subject well represented in major art collections around the world. For more on this subject see the publication Demonic Divine by Rob Linrothe and Jeff Watt, Rubin Museum of Art, New York, 2004.

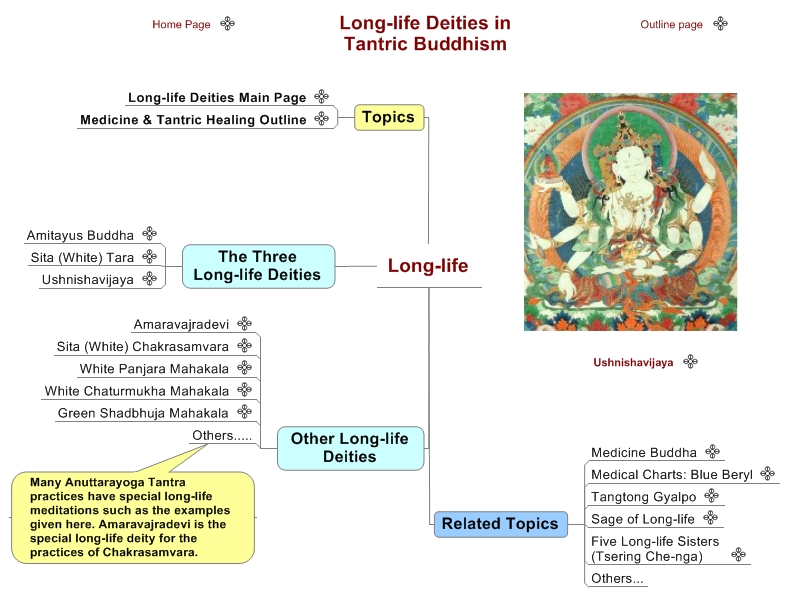

Long-life Deities are a sub-class of deities in Tantric Buddhism. The three principle and well known subjects are Amitayus Buddha, White Tara and Ushnishavijaya. Collectively they are simply known as the 'tse lha nam sum' - Three Long-life Deities. There are a number of other less known deities such as Amaravajradevi, forms of White Chakrasamvara, and all of the specialized forms of the important cycles of Mahakala such as Panjaranata, Chaturmukha, Shadbhuja, and others too numerous and specialized to discuss here. Many of the more specialized forms do not have any painted images or sculptural representations.

Long-life Deities are a sub-class of deities in Tantric Buddhism. The three principle and well known subjects are Amitayus Buddha, White Tara and Ushnishavijaya. Collectively they are simply known as the 'tse lha nam sum' - Three Long-life Deities. There are a number of other less known deities such as Amaravajradevi, forms of White Chakrasamvara, and all of the specialized forms of the important cycles of Mahakala such as Panjaranata, Chaturmukha, Shadbhuja, and others too numerous and specialized to discuss here. Many of the more specialized forms do not have any painted images or sculptural representations.