Jinasagara Avalokiteshvara Outline Page - Updated

The Jinasagara Outline Page has been updated with additional links.

The Jinasagara Outline Page has been updated with additional links.

The Jinasagara Outline Page has been updated with additional links.

The Jinasagara Outline Page has been updated with additional links.

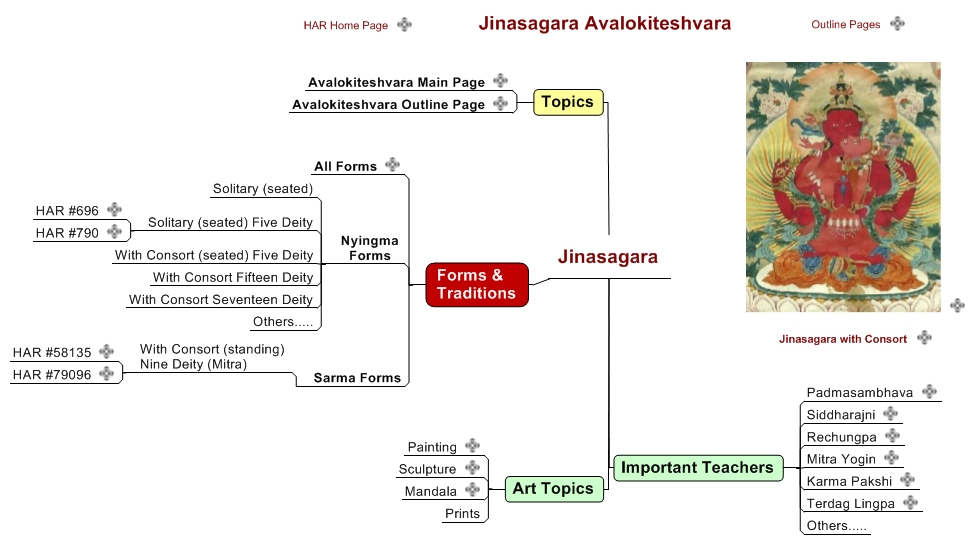

From amongst the many different forms of Avalokiteshvara as a Tantric Deity, the form known as Jinasagara 'Ocean of Conquerors' also has many varieties of forms. There are three main iconographic features that distinguish the different forms of Jinasagara. First, Jinasagara is either in a (1) solitary appearance or he is embracing a consort, and second, (2) posture, he is either standing or seated, and then third (3) relates to the number of retinue figures that are depicted in the mandala. (See Jinasagara Outline Page).

Depending on the various lineages and traditions of practice, new and old, there can be minor differences in the hand objects of both Jinasagara and the consort. The number of arms depicted for the consort may either be two or four. Many of these slight differences are related to the late 'terma' discoveries in the Nyingma Tradition of Tibetan Buddhism in the last three hundred years.

The early forms of the deity are basically distinguished by (1) consort, (2) posture and (3) number of retinue figures in the mandala. The HAR website has two paintings depicting the Five Deity Jinasagara, both have been updated: HAR #696 with Iconographic Program and HAR #790 with Iconographic Program and Figures Numbered & Listed.

Text below from the Tibetan Review:

(TibetanReview.net, Jul14, 2010) A research group cataloging ancient Tibetan books had recently discovered in a Tibetan-inhabited area in Longnan, Gansu province, more than 500 handwritten Bon religious scriptures written in the old Tibetan “language”, reported China’s online Tibet news service eng.tibet.cn Jul 13, citing Gansu Daily. The report called it “an extremely rare and significant discovery”.

The scriptures were reported to contain prayers that monks said when performing religious ceremonies and accounts of life and customs of ancient Tibetans. They are said to be rare and precious materials for studying the medieval Tibetan language, religious beliefs, medicine, astronomy and calligraphy.

The report said that after a few books of the Bon religion had been found in Dunhuang in the early 20th century, this was the first time so many well-protected Bon religious scriptures were discovered in Gansu.

The report said the scriptures were written in abbreviated old Tibetan “language”. It said, “The characters are as clear as (if) they were written yesterday, the illustrations are still colorful and the pages are elegant with classic simplicity.”

The books are believed to have been written between the 9th and 11th century, given the “writing style, choices of words, paper materials and other aspects”.

'Art Depicted in Art' has been updated with twenty more examples added to the group of works making a total of forty (40) paintings. The earliest example on the HAR website is of a 'tangka' painting depicted in a mural from the Par Cave in Western Tibet.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art has a small but great collection of Himalayan style art. The strength is in the large number of good, and early, Tibetan and Nepalese paintings. See the Masterpieces of the Collection, Nepalese Treasures and the Sakya Tradition Masterpieces. Nearly 100 new pieces were added yesterday. There is still more work to be done in cataloguing the collection.

What an uplifting article in yesterdays New York Times (NYT) - Seeking the 'Eye' for Art'.

Have you ever thought to yourself about how some Himalayan style paintings look better than others, that some sculpture are better formed, or more naturalistic? The Himalayan Art Resources Team (HAR) have been working very hard over these many years to exhibit as much art as possible, as many collections as possible, institutional and private. We also believe very strongly in accurate iconographic identifications, tradition and lineage affiliations, and use of original textual sources in cataloguing. Also, recognizing a need in the past few years, many new pages have been added to the HAR site which deal with connoisseurship and the actual looking at art (preferrably real art rather than just an image on a screen, but an image on a screen is at least a start and available to all). See the Masterworks Pages on HAR: Chakrasamvara Masterworks, Panjarnata Mahakala Masterworks, Karmapa Masterworks, etc.

As for the NYT article, we also agree that in the field of Himalayan and Tibetan art studies, the art has been hijacked by other academic disciplines such as Religious Studies (and the study of iconography), Anthropology and Ethnography. The art itself has become relagated to being mere data and props for the discussion of ideas and theories. As the NYT article says "data versus connoisseurship". This article is a wake up call, timely and refreshing.

(See post on the Tricycle Magazine Blog site).

'Art Depicted in Art' collects together all, or as many as found, of the paintings that depict 'art objects' in the composition. Sometimes the process of painting is highlighted in a narrative vignette, or sculpture arranged on a shrine, or sculpture in a small temple. This page is about two-dimensional and three dimensional art represented and depicted in paintings. Sometimes it is difficult to find the vignette, or visual scene, where the art object is depicted. Look carefully and the art within the art will be found.

The painting of the 16th Karmapa is painting following photography. The painting was done from a black and white photograph. Another painting, this time of the 13th Karmapa is painting following sculpture. The image at the top center of the composition is a depiction of a famous metal cast sculpture by the 10th Karmapa, Choying Dorje.

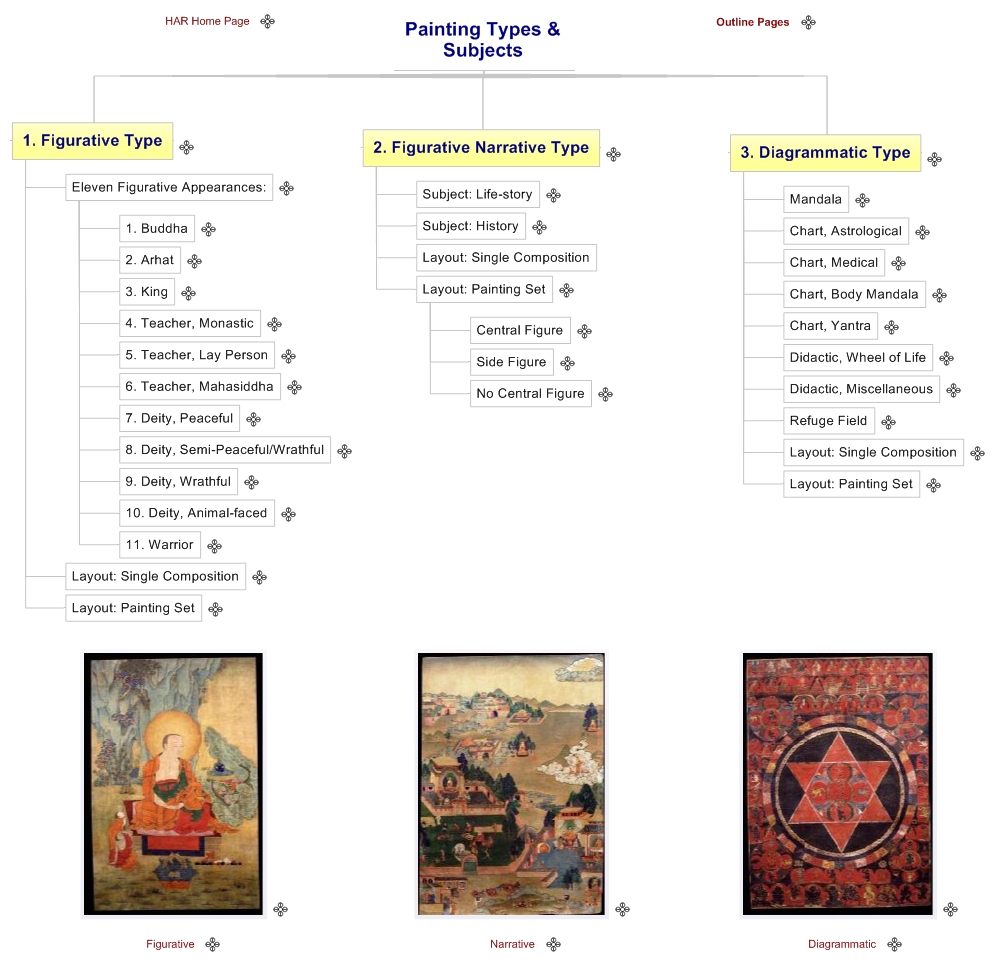

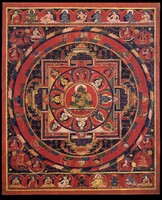

There are Three Main Painting Subjects and Compositional Types in Himalayan Art. The first is Figurative art with depictions of people and deities. The second is Diagrammatic represented by Mandalas, Charts, Refuge Fields and Wheel of Life paintings. The third is the Narrative type which can either have a central figure or no central figure. This last type over-laps with Figurative art.

There are Three Main Painting Subjects and Compositional Types in Himalayan Art. The first is Figurative art with depictions of people and deities. The second is Diagrammatic represented by Mandalas, Charts, Refuge Fields and Wheel of Life paintings. The third is the Narrative type which can either have a central figure or no central figure. This last type over-laps with Figurative art.

Tara, Mother of All Activity: according to Vajrayana Buddhism Tara is a completely enlightened Buddha that typically appears in the form of a beautiful youthful woman sixteen years of age. She made a promise in the distant past that after reaching complete enlightenment she would always appear in the form of a female for the benefit of all beings. She especially protects from the eight and sixteen fears and has taken on many of the early functions originally associated with the deities Avalokiteshvara and Amoghapasha. Practiced in all Schools of Tibetan Buddhism Tara, amongst all of the different deity forms, is likely second in popularity only to Avalokiteshvara. Meditational practices and visual descriptions for Tara are found in all classes of Buddhist tantra, both Nyingma and Sarma (Sakya, Kagyu, Gelug).

The most common forms of Tara are the Green which is considered special for all types of activities, White for longevity and Red for power. The different forms of Tara come in all colours, numbers of faces, arms and legs, peaceful, semi-peaceful and wrathful. There are simple meditational forms representing a single figure and then there are complex forms with large numbers of retinue figures filling all types of mandalas.

Postures in the Iconography of Himalayan art often follow standard descriptions of deities found in the original Sanskrit and Prakrit texts of the Indian sub-continent. Many of these source texts will describe a commonly depicted posture but rather than using the same name consistently will use a different name for that same posture. This naming issue has also continued into the translated Tibetan texts and other languages of the Himalayan regions. The postures and the names are not overly complicated. For the most part the names are simply descriptive of the posture described in the ritual texts and relatively easy to follow in the visual forms depicted in Himalayan paintings and sculpture.

Hand Gestures & Mudras lists the principal buddhas, deities and Indian mahasiddhas and their unique gestures. The list is followed by an alphabetized version with the gestures listed by name.

Depictions of Tibetan and Himalayan teachers are generally depicted using the gestures of Shakyamuni Buddha or one of the Five Symbolic Buddhas. For example Vairochana Buddha is depicted with the hand gesture of Teaching the Dharma. This same gesture is used as the iconic gesture for the famous teachers such as Sakya Pandita, Buton Tamche Kyenpa, Bodong Panchen Chogle Namgyal, Tsongkapa, Ngorchen Kunga Zangpo and a number of Karmapas.

Ninety-nine percent (99%) of all gestures found in Himalayan and Tibetan art are represented in the examples found here which, for the most part, are the original source deities, or subjects, for all of these various gestures and for all subsequent uses and depictions in art.

Hand Drum (Skt.: damaru): a double-sided drum made of wood played in the right hand by twisting the wrist and causing the two strikers to beat against the stretched drum skins usually made of hide or snake skin. The damaru is a common ritual object of India. In Tantric Buddhism the drum is often placed next to the two principal ritual objects, the vajra and bell. The dissipating sound of the drum represents emptiness. The drum is generally made of wood although ivory is popular with wealthy teachers and the nobility. Sometimes two human skullcaps are fashioned into a drum exclusively for wrathful Tantric practices. A larger wooden version, round in shape, of the double-sided hand drum is used in the uniquely Tibetan Buddhist practice known as Cutting (Tib. Chod) popularized by the famous female Tantric practitioner Machig Labdron.

An even larger drum is used in temple rituals and dance performances. This drum (Tibetan: nga) is held with the left hand by a long handle and in the right hand a striker is wielded to produce the sound. For permanent installations this drum can be fastened in a wooden frame or suspended by rope from above.

This beautiful painting of Rakta Yamari, in an Eastern Tibetan Palpung Monastery painting style, has been updated with iconographic information for each of the figures. The most unusual figure is probaby the Vajra Sarasvati - top right corner - not commonly depicted in painting or sculpture. She is associated with the Yamari class of deities and found in the Yamari Tantras.

![]() Himalayan and Tibetan art is primarily focussed on three subjects: Religious Studies, Iconography and Art History. The first of these, religion, is by far the most researched and studied. The second, iconography has come a long way especially with the seminal works of individuals such as Raghu Vira and Lokesh Chandra. Trailing at some distance behind is the study of the actual physical work of art and approaching it from the side of Art History.

Himalayan and Tibetan art is primarily focussed on three subjects: Religious Studies, Iconography and Art History. The first of these, religion, is by far the most researched and studied. The second, iconography has come a long way especially with the seminal works of individuals such as Raghu Vira and Lokesh Chandra. Trailing at some distance behind is the study of the actual physical work of art and approaching it from the side of Art History.

What is it we are actually seeing in a painted composition? What is dictated by religious texts? How much freedom does the artist actually have?

Presented here is a sampling of two translations from the Tibetan language, 11th and 13th century, describing the iconographic appearance of Avalokiteshvara with four arms. These short works also follow closely with the older and original Sanskrit texts. Accompanying the texts are ten examples of Tibetan paintings which would be based either directly on these two texts, or on other similar texts of the time and from the various religious traditions - modelled on the same Sanskrit texts.

Look at these examples, comparing with the translated iconographic descriptions, and note the differences in composition, use of space, colour balancing, variations in ornamentation, body proportions, types and styles of textiles, integration of foreground with background, over-all balance, harmony and symmetry.

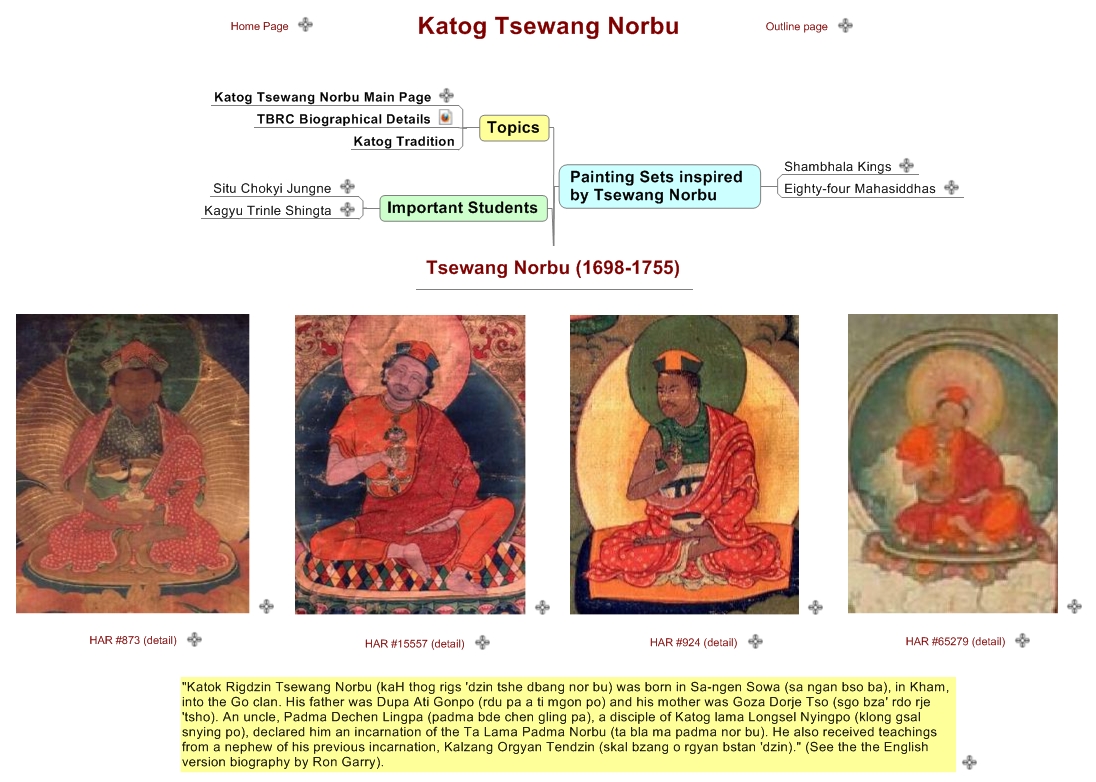

Although one of the most important teachers of 18th century Tibet, Tsewang Norbu is not well represented in painting and sculpture. The HAR website contains one image where Tsewang Norbu is depicted as the large central subject and three other images of paintings where he is portrayed as a secondary figure. It is likely that more images of this important author, teacher and diplomat will turn up in the near future now that we are on the look out for his distinctive iconographic appearance.

Although one of the most important teachers of 18th century Tibet, Tsewang Norbu is not well represented in painting and sculpture. The HAR website contains one image where Tsewang Norbu is depicted as the large central subject and three other images of paintings where he is portrayed as a secondary figure. It is likely that more images of this important author, teacher and diplomat will turn up in the near future now that we are on the look out for his distinctive iconographic appearance.

The Ashmolean Museum of Oxford, England, has re-opened after conducting a major face fift over the last five years. The Himalayan and Tibetan section is expanded with numerous objects on display - mostly sculpture - along with three Tibetan paintings. Additional images from the museum will be added to the Ashmolean section of the HAR website over the next few weeks and broken links will be repaired where possible.

The Ashmolean Museum of Oxford, England, has re-opened after conducting a major face fift over the last five years. The Himalayan and Tibetan section is expanded with numerous objects on display - mostly sculpture - along with three Tibetan paintings. Additional images from the museum will be added to the Ashmolean section of the HAR website over the next few weeks and broken links will be repaired where possible.

Probably one of the most famous Tibetan contemporary artists of his time was the 10th Karmapa, Choying Dorje (1604-1674). It is said that he was trained in a traditional Menri Style and then later studied in a Kashmiri style. What is obviously apparent is that the examples of his work that have come down to us today are in a unique style - the style of Choying Dorje. The three images of paintings below are by the 10th Karmapa Choying Dorje).

See other works of art by Choying Dorje.

For the multi-faced and armed deity, note the gate-like halo surrounding the main figure. It is created to appear as if water, manipulated and suspended. Also see the throne beneath the central subject, rendered with the same treatment, and added figures supporting the pink lotus.

Probably the most unique set of paintings created by Choying Dorje is the life story of Shakyamuni Buddha. No explanation should be required, all that one need to do is look to see how special it is. Look at the colours, the forms, the composition, the rendering of the human figures, animals and birds.

The 10th Karmapa was also famous for his depictions of animals and birds. Notice in this painting of a yellow goddess how the sow and piglets beneath the deity figure are rendered far more life-like with a richness of detail than the yellow deity herself.

A capital 'C' contemporary artist, although sometimes trained traditionally, is often somebody that breaks the rules and is innovative. Sometimes the artist is copied by other artists and a new style is created from that, and at other times no one can follow where that artist has gone.

Choying Dorje is an example of a contemporary artist that was not followed by other artists. It also can't really be said that he was a traditional Tibetan artist either - he was an innovative contemporary artist of his time. I believe that he had a love of art, and of animals - clearly shown in his paintings and biography - and I believe that he created art for art's sake.

A new addition has been added to the Gelug Refuge Field Page. The added painting is very unusual as it seems to present the Buddha with the One Thousand Buddhas of this Age, the Dharma and Sangha as the principal focus. The Guru and Ishtadevata are represented at the top center by Vajrasattva, Tsongkapa and Vajrabhairava. Two Wealth Deities, both forms of Jambhala, are placed to the right and left sides of the Eight Great Bodhisattvas (Sangha) in the bottom tier of the of the composition - just above the pink lotus. The Dharma protectors, represented here by the Four Guardian Kings, are found below the pink lotus amongst the other worldly inhabitants of the Buddhist universe.

The earliest known painting of a Karma Kagyu Refuge Field composition has been updated with all of the figures numbered and named. Also see the colour coded image identifying and naming the various groupings of figures: Guru, Buddha, Dharma, Sangha, Meditational Deities, Protector Deities and Wealth Deities. At the top right and left are Manjushri and Maitreya accompanied by the Six Ornaments and Two Excellent Ones of the Southern Continent. Directly below those are miscellaneous Indian and Tibetan teachers. At the top center interspersed with the early teachers of the Mahamudra Lineage are the Eight Great Siddhas according to the system of Situ Panchen Chokyi Jungne.

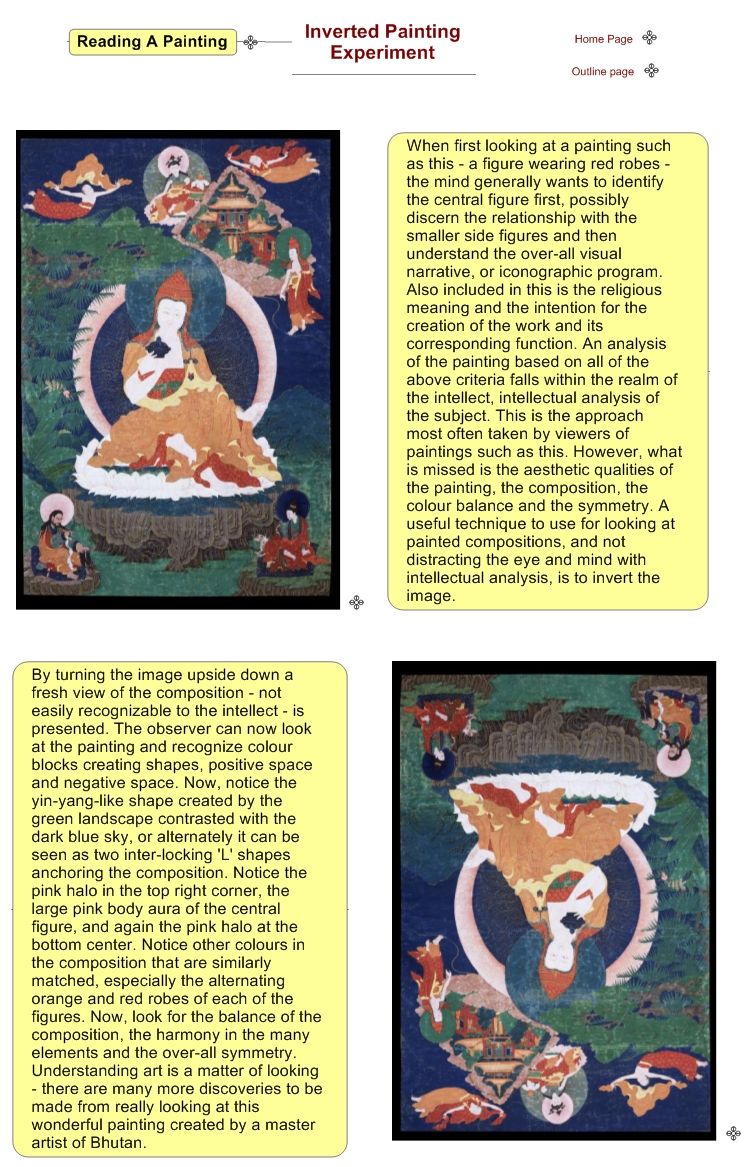

When first looking at a painting such as this - a figure wearing red robes - the mind generally wants to identify the central figure first, possibly discern the relationship with the smaller side figures and then understand the over-all visual narrative, or iconographic program. Also included in this is the religious meaning and the intention for the creation of the work, based on the donor, and its corresponding function. An analysis of the painting based on all of the above criteria falls within the realm of the intellect, intellectual analysis of the subject. This is the approach most often taken by viewers of Himalayan art paintings such as this. However, what is missed is the aesthetic qualities of the painting, the composition, the colour balance and the symmetry. A useful technique to use for looking at painted compositions, that is not distracting to the eye and mind with intellectual analysis, is to invert the image.

When first looking at a painting such as this - a figure wearing red robes - the mind generally wants to identify the central figure first, possibly discern the relationship with the smaller side figures and then understand the over-all visual narrative, or iconographic program. Also included in this is the religious meaning and the intention for the creation of the work, based on the donor, and its corresponding function. An analysis of the painting based on all of the above criteria falls within the realm of the intellect, intellectual analysis of the subject. This is the approach most often taken by viewers of Himalayan art paintings such as this. However, what is missed is the aesthetic qualities of the painting, the composition, the colour balance and the symmetry. A useful technique to use for looking at painted compositions, that is not distracting to the eye and mind with intellectual analysis, is to invert the image.