Sarasvati Page - Updated

The Sarasvati Main Page has been updated with additional images and a list of the more common forms of Sarasvati depicted in Himalayan art. (Also see the Sarasvati Outline Page).

The Sarasvati Main Page has been updated with additional images and a list of the more common forms of Sarasvati depicted in Himalayan art. (Also see the Sarasvati Outline Page).

Ochen Barma 'Blazing with Great Light.' This fierce female deity, classified under the category of Shri Devi (Palden Lhamo), is the wrathful protector aspect of Vajra Vetali the consort of the awesome meditational deity (ishtadevata) Vajrabhairava. Ochen Barma is also an emanation, or wrathful form, of the very peaceful deity Sarasvati, Goddess of Learning, eloquence and literature.

The Three Forms of Sarasvati According to the Vajrabhairava System of Tantra:

1. Vajra Vetali, the female consort in wrathful aspect embracing Vajrabhairava. 2. Sarasvati, the peaceful aspect. 3. Ochen Barma (Blazing with Light) the protector aspect of Vajra Vetali.

Ochen Barma is wrathful in appearance, black in colour with one face and two arms. The yellow hair blazes upwards. In the upraised right hand she holds a staff and a butcher's stick. In the lowered left hand she holds a bag of disease and a lasso. With the right leg bent and the left straight above two prone figures, naked, black in colour, she stands atop a sun disc, lotus and dharmakara - triangle. The flames surrounding her body unfold like a peacock's tail.

There are twelve attendant figures accompanying Ochen Barma. The three most important of those ride animal mounts: horse, mule and wolf.

At the top center is Acharya Bhati. The seated figure at the viewer's right is Manlung Guru of the 13th century. He was a contemporary of Buton Tamche Khyenpa and associated with the Kalachakra Tantra. At the viewer's left is Dranton Dar Drag. The three teachers depicted each pre-date the 13th century and are identified by a name inscription beneath.

Black ground paintings such as this are often used for depicting the most wrathful and horrific images of Tantric Buddhism believing that it enhances those fearsome characteristics of the deity. The creation of black ground paintings was first described in the various Mahakala Tantras (specifically the Twenty-five and Fifty Chapter Tantras). The painting of Ochen Barma is likely from a set of compositions and currently of an unknown number. Only two other images of this rarely seen deity are known to the HAR Team - both minor figures. One image is depicted as a minor figure in a textile tangka preserved in the Palace Museum, Beijing. The other is a painting belonging to a private collection. It was this latter painting depicting Vajrabhairava as the central figure that provided the identification of Ochen Barma by depicting the exact deity and retinue, along with inscriptions, matching the image of the painting HAR #576.

(This painting was formerly incorrectly identified as a form of Ekajati and associated with Shri Devi. It is important to remember that Shri Devi Magzor Gyalmo is also a wrathful protector emanation of Sarasvati). [See TBRC W27414. The Tensrung Gyatso Namtar (bstan srung gya mtsho'i rnam thar) written by Lelung (sle lung)].

The Nepalese Legacy in Tibetan Painting.

September 3, 2010 - May 23, 2011. Rubin Museum of Art, New York.

"For centuries Tibetan artists looked to India for artistic direction. But with the destruction of India's key monasteries in 1203, many artists turned to Nepal's Kathmandu Valley, home to the skilled Newar artists. The Newars' painting style, known as the Beri, was quickly adopted in Tibet, becoming one of the country's most influential artistic styles for four centuries. This exhibition traces the style's development, patronage, and distinctive features." (RMA Website. Read a longer description).

See a selection of objects from the exhibition on the HAR Website.

This painting is iconographically unique because it is the only known composition depicting Vira Vajradharma as a central figure and the only painting known that depicts the two figures of Vajradhara and Vajradharma paired together in a single composition. Vajradharma originates with the Chakrasamvara cycle of Anuttaryoga Tantras and is another form of the Tantric Buddhist primordial Buddha. Vajradharma is red in colour and has two different iconographic forms. The first form, shown in this painting is considered common, Vira Vajradharma, and the second form is regarded as more profound, or uncommon. The second form does not use the initial term 'vira' meaning 'hero' (referring to the appearance of Vira Vajradharma with hand drum and skullcup) and simply goes by the name Vajradharma. The profound form of the primordial Buddha Vajradharma has the same identical appearance as Vajradhara except Vajradharma is red in colour rather than blue. (The primordial Buddha Vajradharma should not be confused with the red form of Avalokiteshvara also with the name Vajradharma [see image])

Unique Iconographic Features:

1. Vira Vajradharma (red) as a central figure.

2. The group of three Vajrayogini figures: Naro, Indra & Maitri.

3. The group of three power deities: Kurukulla, Takkiraja & Ganapati.

4. The inscriptions written on the cloth hangings in front of the two thrones - specifically the Kalachakra monogram.

5. The two Pamting brothers seated on the same lotus.

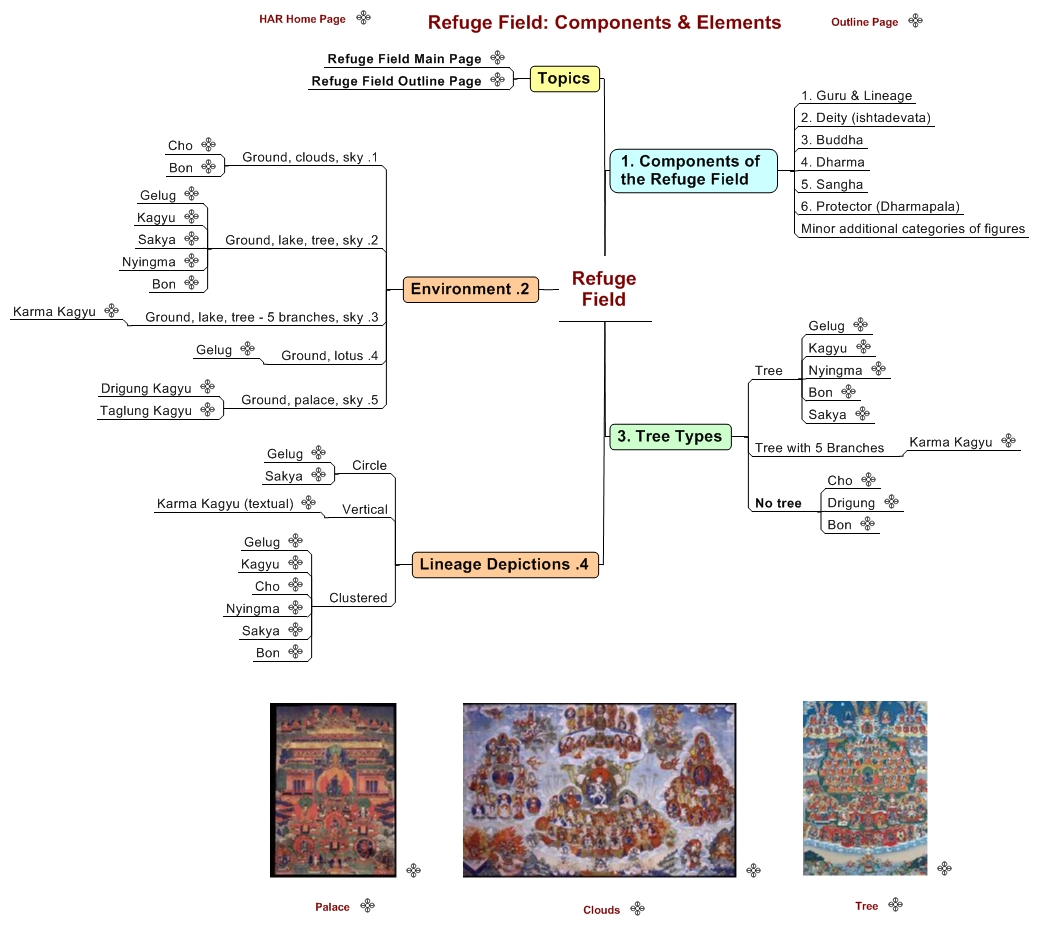

The various Components & Elements of Refuge Field paintings have been catagorized and listed in this new Outline Page. The topic is especially interesting because Refuge Field paintings are a relatively new art subject in Tibetan Buddhism. The two principal components of any Refuge Field painting are (1) the Environment (ground, lake, tree, throne, clouds, etc.) and (2) the actual Field of Accumulation (Refuge objects: Guru, lineage, Buddha, etc.).

The various Components & Elements of Refuge Field paintings have been catagorized and listed in this new Outline Page. The topic is especially interesting because Refuge Field paintings are a relatively new art subject in Tibetan Buddhism. The two principal components of any Refuge Field painting are (1) the Environment (ground, lake, tree, throne, clouds, etc.) and (2) the actual Field of Accumulation (Refuge objects: Guru, lineage, Buddha, etc.).

The earliest paintings depicting a Refuge Field belong to the Gelug tradition and clearly date to the 18th or possibly the late 17th century. Paintings following the iconographic programs of other religious traditions only begin to appear in the 19th century with paintings of the Longchen Nyingtig lineage of the Nyingma followed by Drugpa and Drigung Kagyu lineage depictions. All of the other Tibetan and Himalayan Buddhist lineages, schools and traditions, along with the Bon religion, only adopted the new Refuge Field composition in the early part of the 20th century with some traditions like the Sakya and the Nyingma (aside from the Longchen Nyingtig) only adopting the new composition style in the mid to late 20th century.

Links:

Refuge Field Main Page

Refuge Field Outline Page

Refuge Field: Components & Elements

An additional painting, HAR #66432, has been added to the Karmapa Masterworks Page on the HAR website. This painting is unusual because of the artist's individual style, the clarity of the various elements, rendering of figures, and the small narrative vignettes at the top right and left of the composition. The artist's name is currently unknown. Although the painting looks as if it should be a Karma Kagyu creation there are many elements in the details of the composition indicating that it is likely a Drugpa Kagyu painting done in honor of the 9th Karmapa. When more paintings from the complete set are found then the full iconographic program will be made clear.

Wangchug Dorje, the 9th Karmapa, (1555-1603), was a great traveler, scholar and practitioner, well educated and a moderately prolific writer. Two of his more important literary compositions on the philosophy of mahamudra were the 'Ocean of Certainty' and 'Eliminating the Darkness of Ignorance.' Amongst his many famous students was Jonang Taranata and other great masters of the time.

The central figure in the painting is identified as the 9th Karmapa, aside from the black hat, because of the right hand upraised in a gesture of blessing and the left hand holding a vase. The 9th Karmapa is generally depicted either in this manner or with the right hand extended across the knee and the left hand alternately holding a book in the lap. When looking at images of the sixteen Karmapas that appear in art, with general iconographic characteristics, no other from the fifteen has this consistent specific depiction, albeit with two variations.

The large central figure of Wangchug Dorje wears the typical black hat common to all recognized rebirths in the Karmapa incarnation lineage. He holds the right hand up to the heart in a gesture of blessing and the left hand in the lap holds a long-life vase. Wearing the red and orange robes of a fully ordained monk, he also wears an outer meditation cloak, gold and richly patterned. Karmapa sits on a cushioned throne with an ornate backrest of Chinese style with two dragon heads looking inwards at the seated figure. A large black lacquer table supports victuals and libations while again in front two more tables, pink and blue, present offerings, jewels and precious substances - real and imagined.

In the foreground, four attendant figures wearing monastic robes and red caps attend to the seated central figure of Karmapa. The attendant at the upper left offers a hat, large and fan-like, held with a white scarf. The attendant below offers tea from a round white teapot, held aloft, with a white scarf. The attendant at the upper right offers a Tibetan folio text, red and long, with a white scarf. The attendant below waves a metal censor, wafting incense, held by a gold chain in the right hand. The left hand holds a bag of precious incense in a striped woven cloth bag decorated with frills along the bottom.

Directly behind and above Karmapa is a tree trunk, with curved and knotty branches, tall, extending into the clouds, white, pink, yellow and blue, which pool to form a pond of blue water, rolling waves, with lotuses supporting a throne and pink lotus seat for the primordial Buddha Vajradhara, blue in colour. On the viewer's left is the Indian mahasiddha Tilopa and on the right side is Naropa - both are accompanied by an attendant figure - female.

Slightly lower than the top center, on the left side, is Marpa Chokyi Lodro and consort, Dagmema. Below that is the famous student of Milarepa, Gampopa Sonam Rinchen, wearing the robes of a monk and the hat which he designed. To the side of the throne sits Pagmodrupa - founder of the Eight Minor Kagyu Traditions (such as Drugpa Kagyu), slightly disheveled, balding and with a growth of facial hair.

Below Vajradhara on the right side is Milarepa, yogi and poet, student of Marpa, wearing the traditional white robes of a yogi and a red meditation belt, cupping his ear while singing to six figures seated in front. Below that is once again Pagmodrupa, with monastic robes, seated in a grass meditation hut, situated in a dense green forest.

Although this painting depicts a Karmapa as the central figure it is most likely a Drugpa Kagyu creation and part of a much larger composition. At this time the intention of the complete creation is not yet understood.

There are no apparent inscriptions on the front of the painting. There are however inscriptions on the verso but they were applied long after the painting was created. Some inscriptions are in a modern gold paint and others are written with a pen. Likely the inscriptions were applied by a former owner in the 20th century. Therefore, the inscriptions on the back are neither informative nor reliable.

This painting is the first composition in a set of paintings. We know this because at the back of the painting, top of the cloth mounting, there is the single Tibetan word 'tsowo.' This means 'main' or' principal.' It is the standard term written on the back of a painting to indicate which painting is number 'one' or the 'center piece' in a set. There is no way at this time to determine how many other paintings were in the complete set.

The Miniature Paintings of Mongolian Buddhism: Tsaklis, Thangkas and Burhany Zurags by Stevan Davies. Professor of Religious Studies, Misericordia University. April 08, 2010. (Asianart.com Website).

The village of Tsarang is just south of the walled town of Lo Monthang, the capital of the Kingdom of Mustang in North Western Nepal. The village of Tsarang (Charang) has numerous stupa structures, a monastery (gompa) and a fortress (dzong). The monastery is made up of several buildings and structures. Some are in the process of being renovated and others are in a state of serious disrepair. The inner walls of the main temple are painted with murals depicting the deities of the Medicine Buddha mandala. They have recently been cleaned and restored. It has been suggested by some local informants that depictions and rituals of Medicine Buddha are a special object of devotion in the Kingdom of Mustang and can be found in the temples of almost every Mustang village.

By far one of the most interesting buildings in the small walled monastic complex is located at the back of the property, looking like nothing but a ruin, almost falling over a cliff. The structure is referred to locally as the Ani Gompa, or Ani Lhakang (nunnery). Navigating the only entrance, a set of small wooden double doors, flanked by a Wheel of Life and murals of the Four Guardian Kings, arriving inside, it is imediately noticable that the roof has large gaping holes, numerous rafters with blue sky behind. The floor is an uneven surface of mud and dirt and the entire place seems like it could collapse at any momenent. Yet despite all of that, the inner walls are completely decorated with brightly coloured murals, some of which appear to have been cleaned and restored in very recent years. It is like an oasis of colour and palacial grandeur, unexpected, awesome and immediately comforting and strangely well grounded, stable and solid.

The inner layout of the room, clearly a temple or shrine room of some sort, is not completely typical. The main inner wall at the front of the room (across from the door) has a large depiction of the Buddha Vajradhara, the primordial Buddha, surrounded by the lineage teachers of the Sakya Lamdre - based on the Hevjra Tantra and teachings of the Indian mahasiddha Virupa (depicted with six different forms in the murals of the main temple). On the viewer's left hand side is a very large painting of Padmasambhava surrounded by a Nyingma lineage. On the right side of the room is a large painting of a Drugpa Kagyu teacher surrounded by a Drugpa Kagyu lineage. The side walls of the room appear to depict the Five Symbolic Buddhas accompanied by smaller buddhas representing the One Thousand Buddhas of the Age. To the immediate right and left of the entrance are protector deities of the Sakya Tradition on one side and protectors of the Drugpa Kagyu Tradition of the other side.

Despite being called an Ani Gompa, the structure is more likely to be a Lamdre Lhakang or a building created for use during the Monastic Summer Retreat - and later painted. As a backdrop to the monastery, on the steep cliff sides of the valley surrounding the village are evidence of extensive cave dwellings both for religious as well as secular use. Only some of these caves are accessible, most are not. Only a small percentage of the caves have been explored by trained climbers and cultural specialists.

Tsarang Village

Main Temple

Ani Lhakang

Village Fortress (Dzong)

The Chushar area of Northern Mustang, West Nepal, is home to numerous ancient cave sites containing Buddhist murals and artifacts dating back 500 years or more. According to the local inhabitants of the area there are four important famous cave sites called: 1) Konchog Ling, 2) Ritse Ling, 3) Ganden Ling and 4) ... ling. All four sites have remains of murals with some in very good condition and some in poor condition.

The iconographic program in this small Avalokiteshvara Chapel located on the ground floor of Shalu Monastery, in the circumambulatory passage, follows the tradition of the Shangpa Kagyu School of Tibetan Buddhism. It is very likely that these murals are the earliest to represent the Shangpa Kagyu Tradition. The principal deity is Avalokiteshvara, central in the small chapel, and the lineage depictions follow the tradition of the Tibetan Lama Kyergangpa (1143-1216).

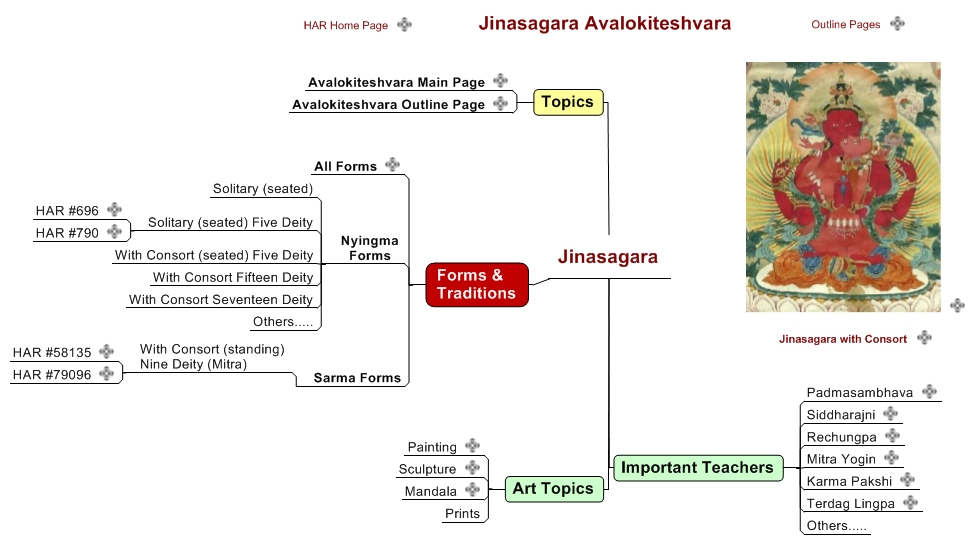

The Jinasagara Outline Page has been updated with additional links.

The Jinasagara Outline Page has been updated with additional links.

From amongst the many different forms of Avalokiteshvara as a Tantric Deity, the form known as Jinasagara 'Ocean of Conquerors' also has many varieties of forms. There are three main iconographic features that distinguish the different forms of Jinasagara. First, Jinasagara is either in a (1) solitary appearance or he is embracing a consort, and second, (2) posture, he is either standing or seated, and then third (3) relates to the number of retinue figures that are depicted in the mandala. (See Jinasagara Outline Page).

Depending on the various lineages and traditions of practice, new and old, there can be minor differences in the hand objects of both Jinasagara and the consort. The number of arms depicted for the consort may either be two or four. Many of these slight differences are related to the late 'terma' discoveries in the Nyingma Tradition of Tibetan Buddhism in the last three hundred years.

The early forms of the deity are basically distinguished by (1) consort, (2) posture and (3) number of retinue figures in the mandala. The HAR website has two paintings depicting the Five Deity Jinasagara, both have been updated: HAR #696 with Iconographic Program and HAR #790 with Iconographic Program and Figures Numbered & Listed.

Text below from the Tibetan Review:

(TibetanReview.net, Jul14, 2010) A research group cataloging ancient Tibetan books had recently discovered in a Tibetan-inhabited area in Longnan, Gansu province, more than 500 handwritten Bon religious scriptures written in the old Tibetan “language”, reported China’s online Tibet news service eng.tibet.cn Jul 13, citing Gansu Daily. The report called it “an extremely rare and significant discovery”.

The scriptures were reported to contain prayers that monks said when performing religious ceremonies and accounts of life and customs of ancient Tibetans. They are said to be rare and precious materials for studying the medieval Tibetan language, religious beliefs, medicine, astronomy and calligraphy.

The report said that after a few books of the Bon religion had been found in Dunhuang in the early 20th century, this was the first time so many well-protected Bon religious scriptures were discovered in Gansu.

The report said the scriptures were written in abbreviated old Tibetan “language”. It said, “The characters are as clear as (if) they were written yesterday, the illustrations are still colorful and the pages are elegant with classic simplicity.”

The books are believed to have been written between the 9th and 11th century, given the “writing style, choices of words, paper materials and other aspects”.

'Art Depicted in Art' has been updated with twenty more examples added to the group of works making a total of forty (40) paintings. The earliest example on the HAR website is of a 'tangka' painting depicted in a mural from the Par Cave in Western Tibet.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art has a small but great collection of Himalayan style art. The strength is in the large number of good, and early, Tibetan and Nepalese paintings. See the Masterpieces of the Collection, Nepalese Treasures and the Sakya Tradition Masterpieces. Nearly 100 new pieces were added yesterday. There is still more work to be done in cataloguing the collection.

What an uplifting article in yesterdays New York Times (NYT) - Seeking the 'Eye' for Art'.

Have you ever thought to yourself about how some Himalayan style paintings look better than others, that some sculpture are better formed, or more naturalistic? The Himalayan Art Resources Team (HAR) have been working very hard over these many years to exhibit as much art as possible, as many collections as possible, institutional and private. We also believe very strongly in accurate iconographic identifications, tradition and lineage affiliations, and use of original textual sources in cataloguing. Also, recognizing a need in the past few years, many new pages have been added to the HAR site which deal with connoisseurship and the actual looking at art (preferrably real art rather than just an image on a screen, but an image on a screen is at least a start and available to all). See the Masterworks Pages on HAR: Chakrasamvara Masterworks, Panjarnata Mahakala Masterworks, Karmapa Masterworks, etc.

As for the NYT article, we also agree that in the field of Himalayan and Tibetan art studies, the art has been hijacked by other academic disciplines such as Religious Studies (and the study of iconography), Anthropology and Ethnography. The art itself has become relagated to being mere data and props for the discussion of ideas and theories. As the NYT article says "data versus connoisseurship". This article is a wake up call, timely and refreshing.

(See post on the Tricycle Magazine Blog site).

'Art Depicted in Art' collects together all, or as many as found, of the paintings that depict 'art objects' in the composition. Sometimes the process of painting is highlighted in a narrative vignette, or sculpture arranged on a shrine, or sculpture in a small temple. This page is about two-dimensional and three dimensional art represented and depicted in paintings. Sometimes it is difficult to find the vignette, or visual scene, where the art object is depicted. Look carefully and the art within the art will be found.

The painting of the 16th Karmapa is painting following photography. The painting was done from a black and white photograph. Another painting, this time of the 13th Karmapa is painting following sculpture. The image at the top center of the composition is a depiction of a famous metal cast sculpture by the 10th Karmapa, Choying Dorje.

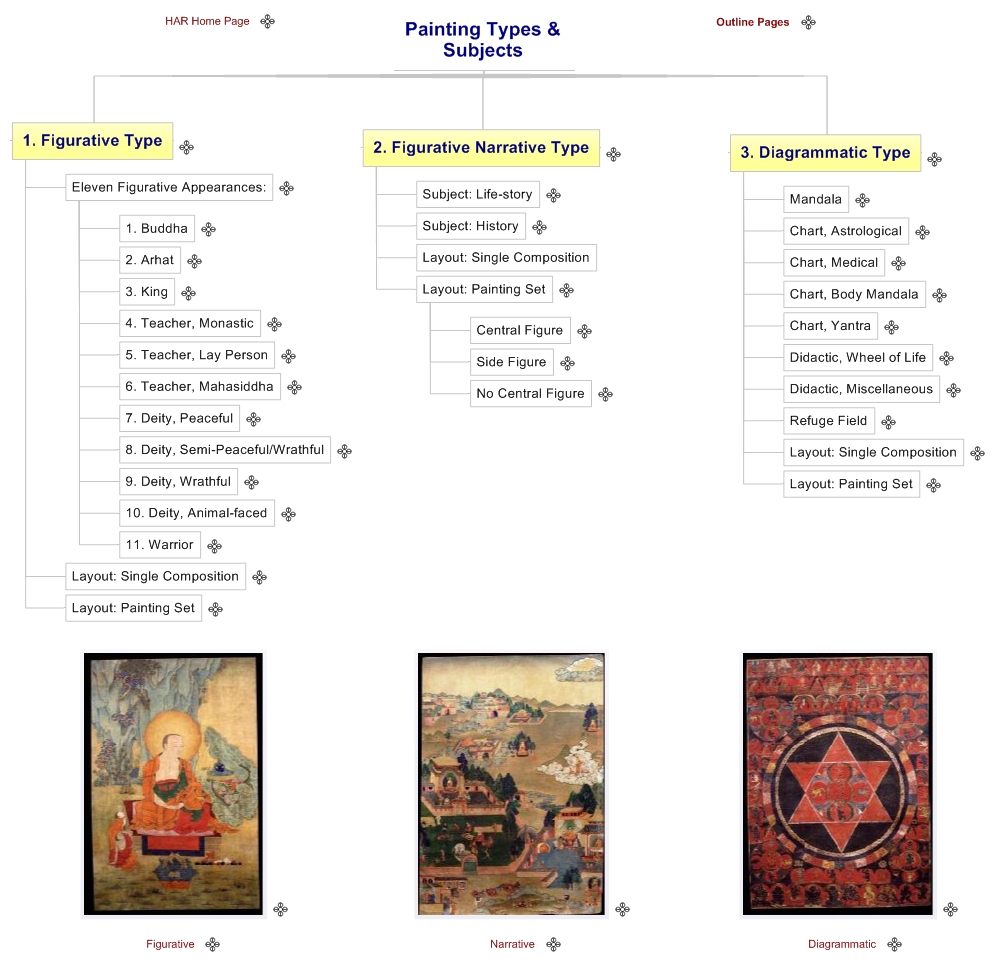

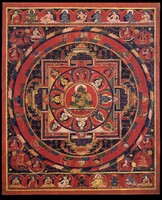

There are Three Main Painting Subjects and Compositional Types in Himalayan Art. The first is Figurative art with depictions of people and deities. The second is Diagrammatic represented by Mandalas, Charts, Refuge Fields and Wheel of Life paintings. The third is the Narrative type which can either have a central figure or no central figure. This last type over-laps with Figurative art.

There are Three Main Painting Subjects and Compositional Types in Himalayan Art. The first is Figurative art with depictions of people and deities. The second is Diagrammatic represented by Mandalas, Charts, Refuge Fields and Wheel of Life paintings. The third is the Narrative type which can either have a central figure or no central figure. This last type over-laps with Figurative art.

Tara, Mother of All Activity: according to Vajrayana Buddhism Tara is a completely enlightened Buddha that typically appears in the form of a beautiful youthful woman sixteen years of age. She made a promise in the distant past that after reaching complete enlightenment she would always appear in the form of a female for the benefit of all beings. She especially protects from the eight and sixteen fears and has taken on many of the early functions originally associated with the deities Avalokiteshvara and Amoghapasha. Practiced in all Schools of Tibetan Buddhism Tara, amongst all of the different deity forms, is likely second in popularity only to Avalokiteshvara. Meditational practices and visual descriptions for Tara are found in all classes of Buddhist tantra, both Nyingma and Sarma (Sakya, Kagyu, Gelug).

The most common forms of Tara are the Green which is considered special for all types of activities, White for longevity and Red for power. The different forms of Tara come in all colours, numbers of faces, arms and legs, peaceful, semi-peaceful and wrathful. There are simple meditational forms representing a single figure and then there are complex forms with large numbers of retinue figures filling all types of mandalas.

Postures in the Iconography of Himalayan art often follow standard descriptions of deities found in the original Sanskrit and Prakrit texts of the Indian sub-continent. Many of these source texts will describe a commonly depicted posture but rather than using the same name consistently will use a different name for that same posture. This naming issue has also continued into the translated Tibetan texts and other languages of the Himalayan regions. The postures and the names are not overly complicated. For the most part the names are simply descriptive of the posture described in the ritual texts and relatively easy to follow in the visual forms depicted in Himalayan paintings and sculpture.