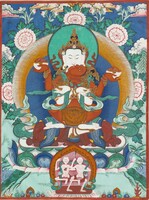

White Chakrasamvara is a meditational deity belonging to the Anuttarayoga classification of Buddhist Tantra. There are also subsidiary forms and practices of White Chakrasamvara that are specifically intended for the prolongation of life span.

The white form of the deity was popularized in Tibet and the Himalayan regions by the Indian teacher Mitra Yogin and the Kashmiri teacher Shakyashri Bhadra. The Mitra Yogin form of the deity is solitary (without a consort), in a standing posture, and part of a twenty-nine deity mandala. This form of the deity can be found in all of the Sarma traditions although practiced less frequently than the Shakyashri Bhadra tradition.

The Shakyashri Bhadra form of the deity is in a standing posture and partnered with Vajrayogini, red in colour. There are no retinue or accompanying mandala figures. The Sakya, Jonang, Kagyu and Gelug traditions mainly follow this tradition of White Chakrasamvara practice. There is also a long life practice associated with this deity, however the appearance remains the same.

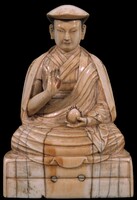

The tradition of Lama Umapa, a teacher of Tsongkapa, describes the deity as white with a red consort, both in a seated posture. The male holds two long-life vases in the right and left hands. The consort holds two skullcups in the right and left hands. This form of Chakrasamvara with consort functions as a long life deity, unique to the Gelug Tradition, and appears to have been developed as a Tibetan creation.