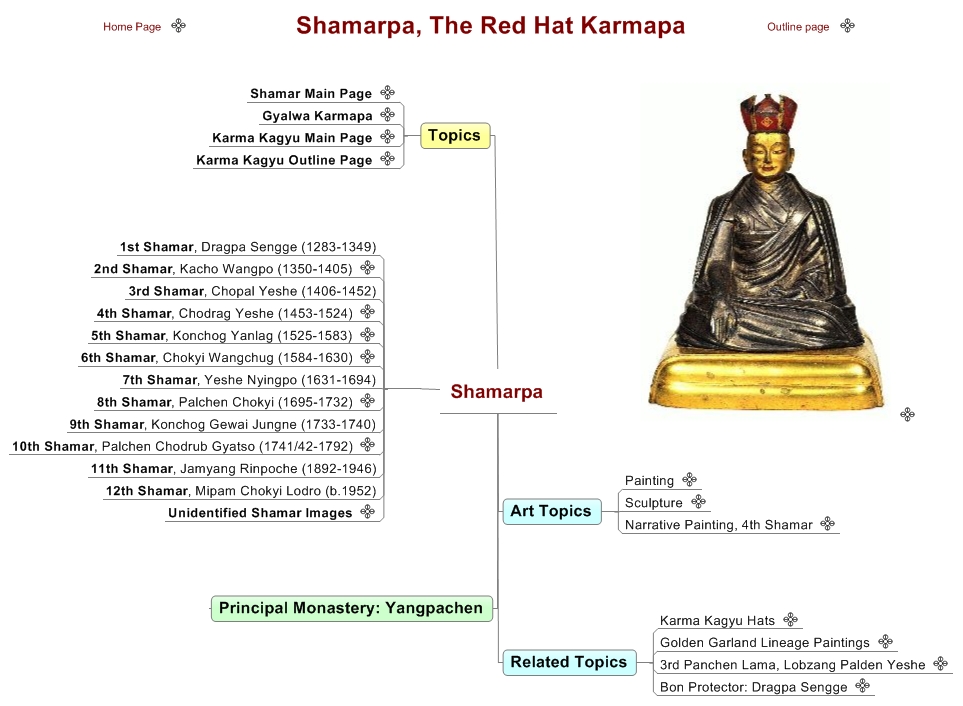

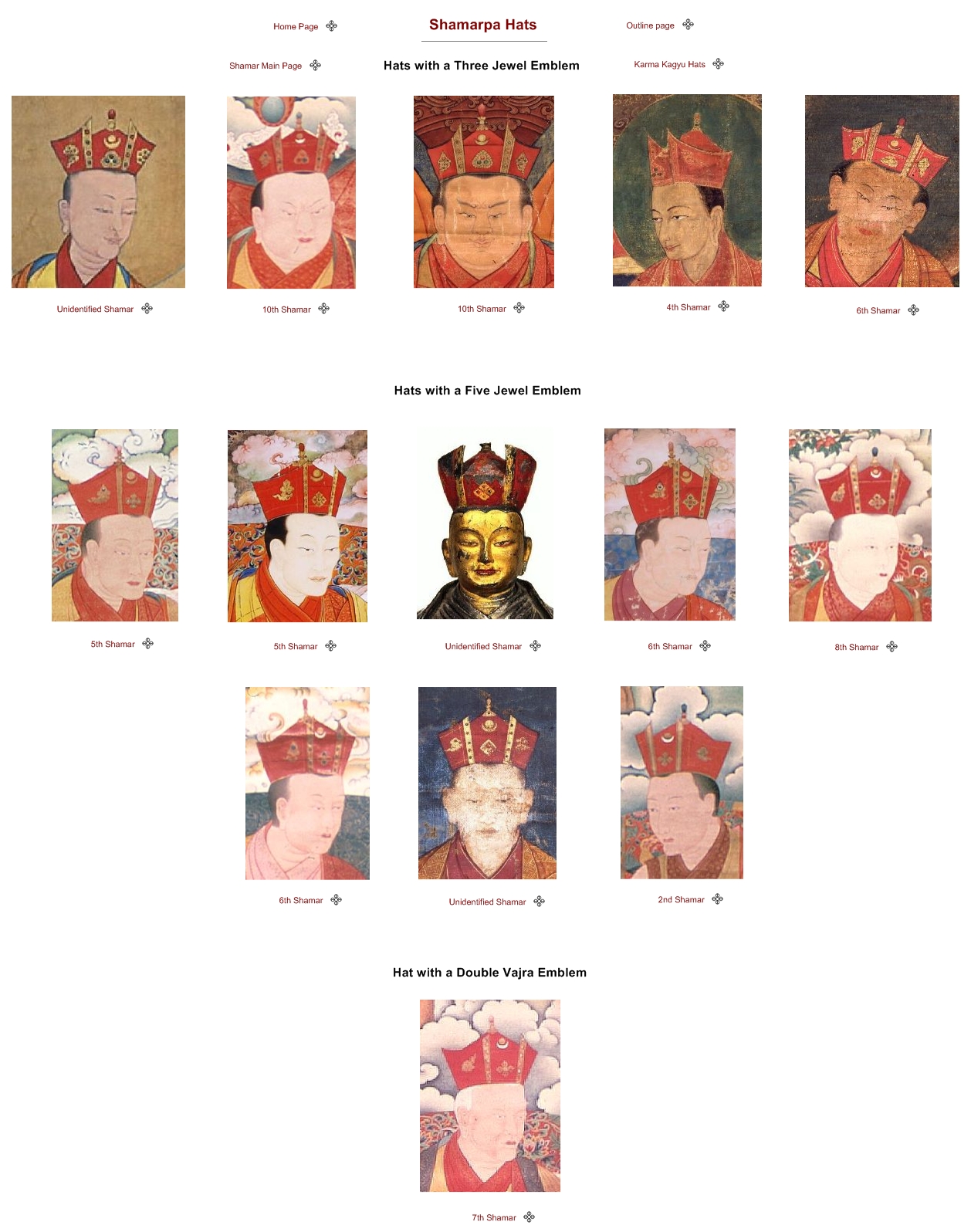

The red hat (sha marpo) of the Shamar Lamas, of the Karma Kagyu Tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, is patterned after the famous black hat of the Gyalwa Karmapas. The 2nd Shamar, Kacho Wangpo (1350-1405), was the first to have a red copy of the black hat, said to be a gift from his teacher the 4th Karmapa, Rolpai Dorje (1340-1383). Later, the Tsurpu Gyaltsab incarnations and the Tai Situ incarnations, also of the Karma Kagyu, would follow form and adopt the same basic design of the red hat, patterned on the black hat, although with slight stylistic modifications.

The red hat (sha marpo) of the Shamar Lamas, of the Karma Kagyu Tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, is patterned after the famous black hat of the Gyalwa Karmapas. The 2nd Shamar, Kacho Wangpo (1350-1405), was the first to have a red copy of the black hat, said to be a gift from his teacher the 4th Karmapa, Rolpai Dorje (1340-1383). Later, the Tsurpu Gyaltsab incarnations and the Tai Situ incarnations, also of the Karma Kagyu, would follow form and adopt the same basic design of the red hat, patterned on the black hat, although with slight stylistic modifications.

The 2nd Gyaltsab, Tashi Namgyal (1490-1518) recieved an orange hat from the 7th Karmapa, Chodrag Gyatso (1454-1506). The 1st Situ, Chokyi Gyaltsen (1377-1448), recieved his title of 'Kenting Tai Situ' from the Chinese emperor Yungle but didn't recieve his red hat until the 5th incarnation of Tai Situ, Chokyi Gyaltsen Palzang (1586-1657). That hat was given by the 9th Karmapa Wangchug Dorje (1556-1602/03).

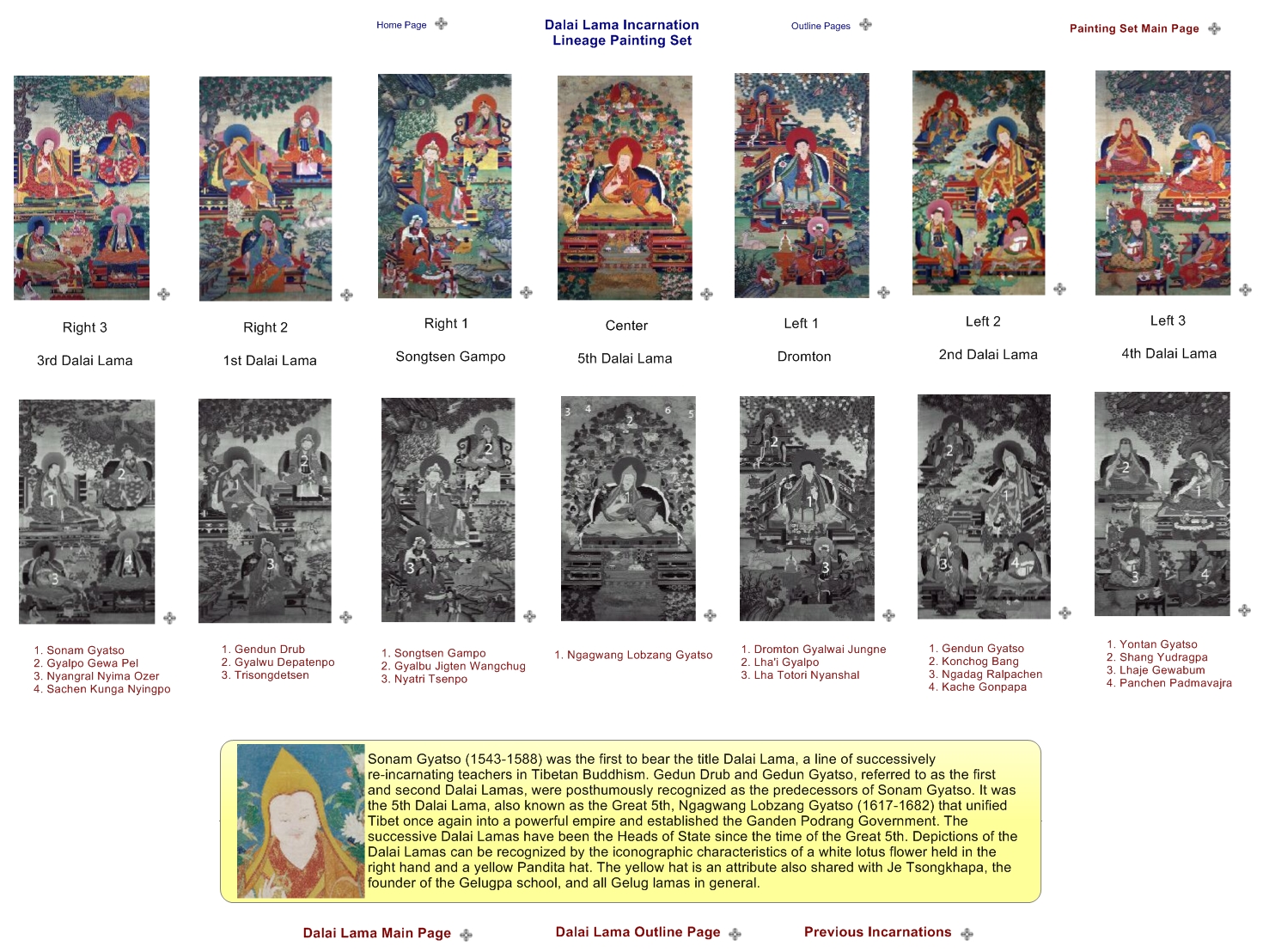

According to the history of the Karma Kagyu tradition the fifth Karmapa Dezhin Shegpa (1384-1415) was presented a gift of a black hat by the Chinese emperor Yungle. However, according to Mongolian history the first black hat was a gift of Mongke Khan to the 2nd Karmapa, Karma Pakshi. Despite its true origins, this black hat has become the principal identifying characteristic and iconographic attribute in the depictions of the Karmapa incarnation lineage and likewise for the Shamarpa incarnation lineage.

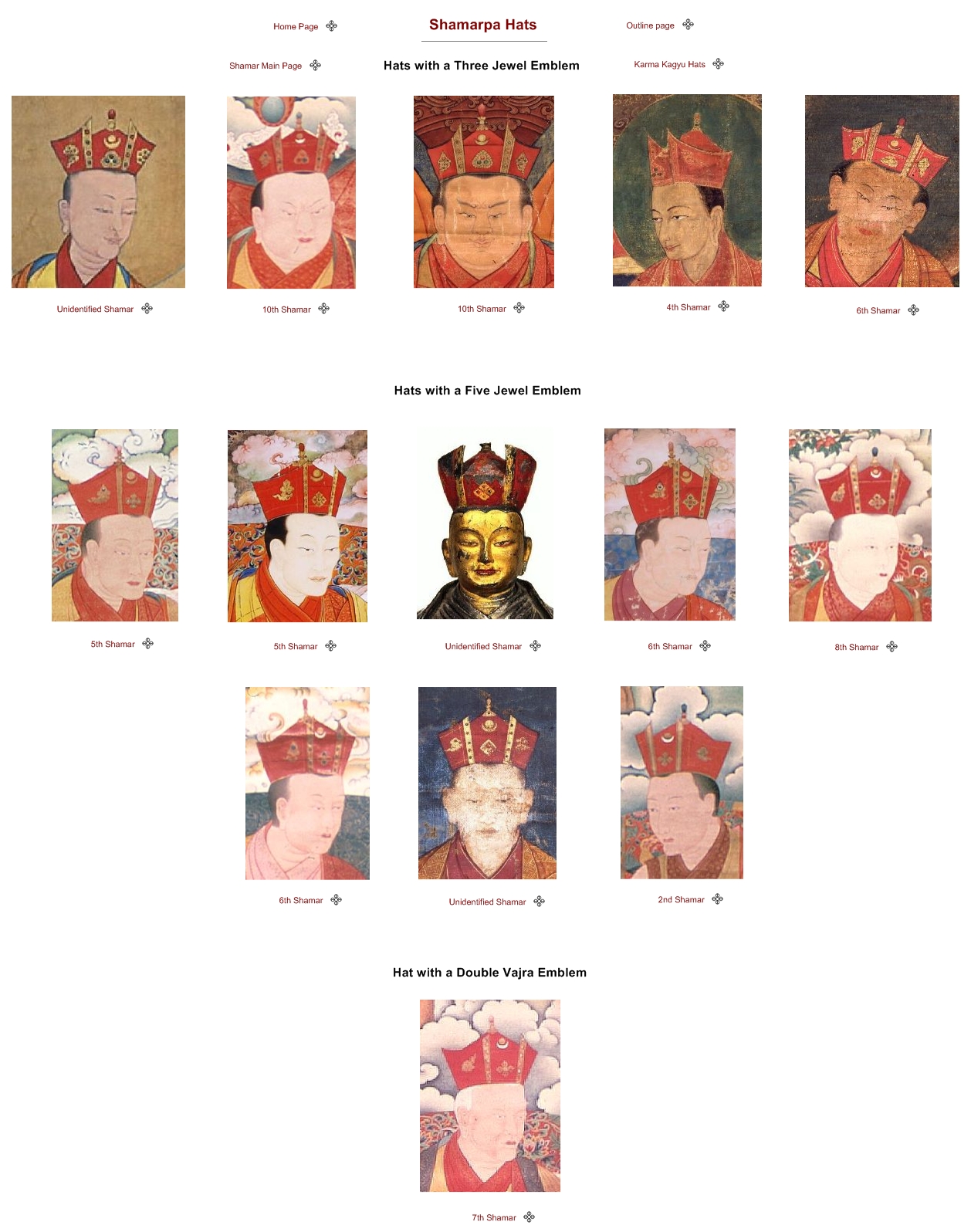

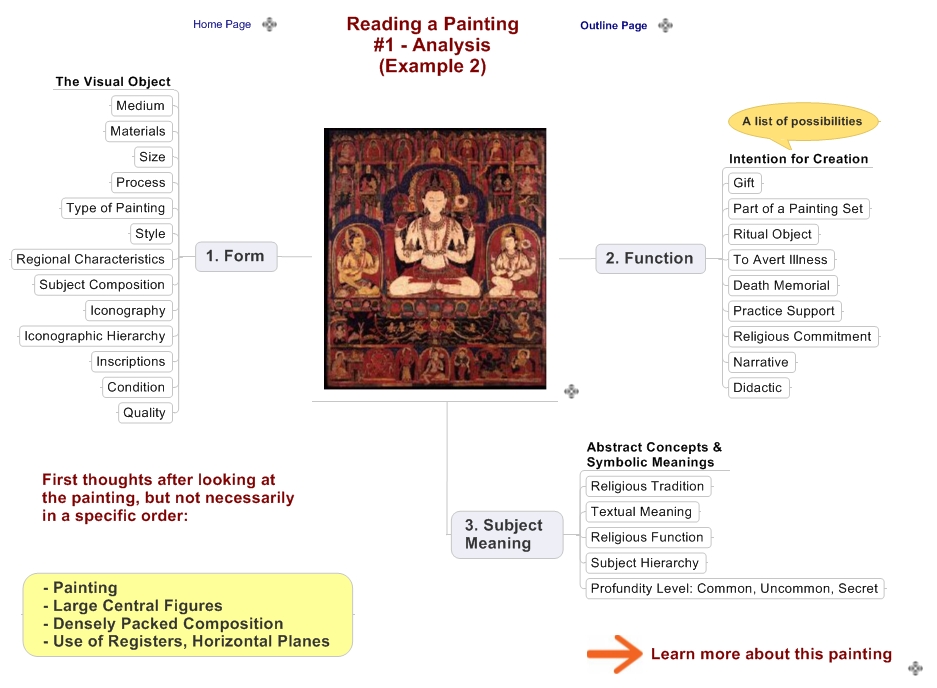

Characteristics of the Shamar Hat

1. Red in colour

2. Round with upturned flaps

3. Front marked with a three or five jewel emblem

4. Sides decorated with cloud pattern trailing to the back

5. Peaked with a gold finial and a large jewel

The shape of the hat itself is more like a cap and similar to a Mongolian or Chinese court minister's head gear. Aside from the colour, black versus red, the cloud pattern on the side of both the Karmapa and Shamarpa hats differs slightly with the pattern of the Shamar hat placed opposite to that of the black hat. The cloud pattern of the Shamar hat, on the right and left side, almost always trails to the back, which means that the cloud pattern appears to be floating forward of the cap. The black hat pattern has the trail, or tail, of the cloud at the front of the cap.

The ornament on the front of the red Shamar hat is tyically either a three jewel emblem/motif, or a five jewel emblem (the latter reminiscent of a stylized double vajra possibly imitating the double vajra of the black hat). In one instance on the HAR website there is a Shamar hat with a double vajra emblem in a painted depiction of the 7th Shamar, Yeshe Nyingpo.

For sculptural representations of the Shamar Lamas, and the red hat, often a simple flat four sided diamond shape is used as the front emblem of the cap. This is also common for sculptural depictions of the Gyalwa Karmapa, Tai Situ and Gyaltsab Lamas.

Observing 20 Shamarpa images on the HAR site, both painting and sculpture, 3 have a simple diamond shaped emblem, 6 have a three jewel emblem, 10 have a five jewel emblem, and only 1 has a double vajra emblem (vishva vajra).

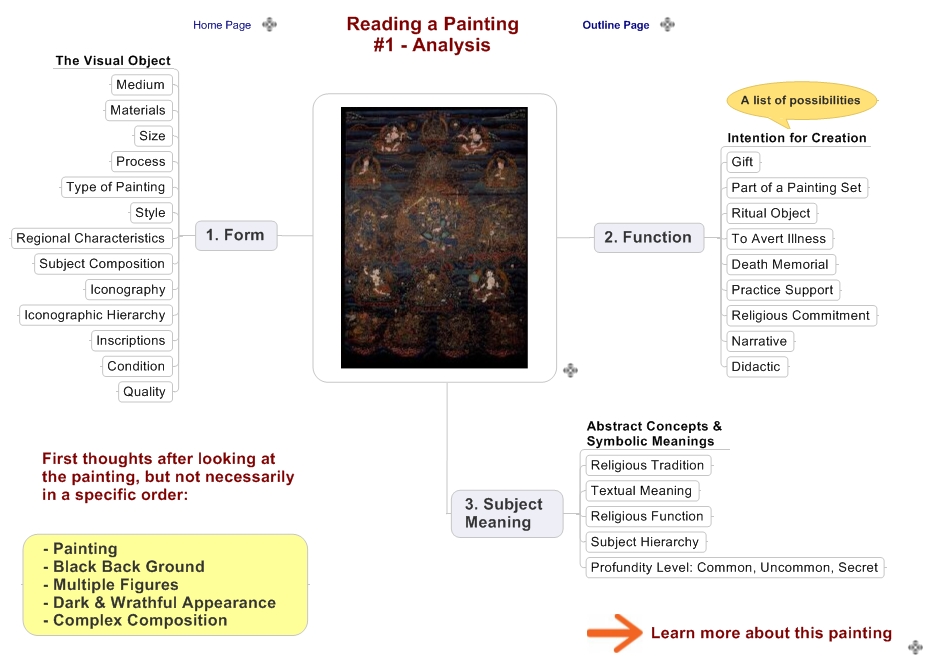

Typically it is the black hat of the Karmapa that has the double vajra symbol. It is important to know that there is an official black with gold and jewel decorations and then there is a simple black cap made of cloth with a diamond front emblem, also of cloth. The simple cloth cap is worn by the Karmapas for less formal occasions. These two types of hats can be confused when rendered as sculptural objects. In paintings it is readily clear by the brightly painted gold and jewel ornaments which hat is being depicted.

Characteristics of the Karmapa Hat

1. Black in colour

2. Round with upturned flaps

3. Front marked with double vajra emblem & a sun and moon above

4. Sides decorated with cloud pattern trailing to the front

5. Sometimes, no cloud pattern, or no clouds for the first four Karmapas

6. Peaked with a gold finial and a large red ruby

Later, the Karmapa's regeant at Tsurpu Monastery, the Tsurpu Gyaltsab incarnation, would also adopt the red cap and generally maintain the same identical ornamentation as the black hat of the Karmapas: double vajra, sun and moon, cloud pattern at the sides and trailing to the front. However, in some depictions of the Gyaltsab Lamas they wear an orange hat with jewels on the front.

The red hat of the Tai Situ incarnations appears to vary in colour between red and orange, most often having a three jewel emblem on the front and the cloud pattern trailing to the back. More importantly, the Tai Situ hat is also slightly different from all of the others in that it has two notches, or divits, along the top of the up-turned right and left flaps, directly above the cloud pattern on the sides. However, this notch is not consistent from one depiction to the next but common enough to be an important characteristic unique to the Tai Situs and their particular hat. Following that inconsitency, the cloud pattern of the Situ cap sometimes trails to the front, like the black hat, and not always to the back, as is standard for the Shamar hat. Although in an early 17th century painting of the 1st Tai Situ he is depicted with a red hat, not orange, and a five jewel emblem, not three, with the clouds trailing to the front, not back, and the two notches on the right and left sides of the cap clearly visible - the notches becoming more common on the Situ hats in later centuries.

Characteristics of the Tai Situ Hat

1. Red in colour

2. Round with upturned flaps

3. Front marked with a three or five jewel emblem

4. Sides decorated with cloud pattern trailing to the back

5. notch on the top of the right and left upturned flaps

6. Peaked with a gold finial and a jewel

It should now be quite clear that the most consitent and recognizable characteristics for all of these hats, especially for the Shamar, is that the Karmapa's hat is black, the Shamarpa's hat is red as is the Gyaltsab and sometimes the Tai Situ's hat. For the Shamarpa and his hat the most important characteristic to recognize is the red colour of the hat with the cloud pattern trailing towards the back followed by the second characteristic of the three or five jewel emblem on the front of the hat. Aside from these few characteristics, that are not necessarily followed religiously, the only way to tell the difference between a Shamar hat and a Situ hat is the hand gestures and attributes of the lama being depicted beneath the hat. The painting composition, inscriptions, facial expression of the figure, and the placement of secondary figures in a composition in relation to the central figure are all important in determining the true identification of a Shamar hat.

Shamarpa Main Page

Shamarpa Outline Page

Karma Kagyu Hats Page

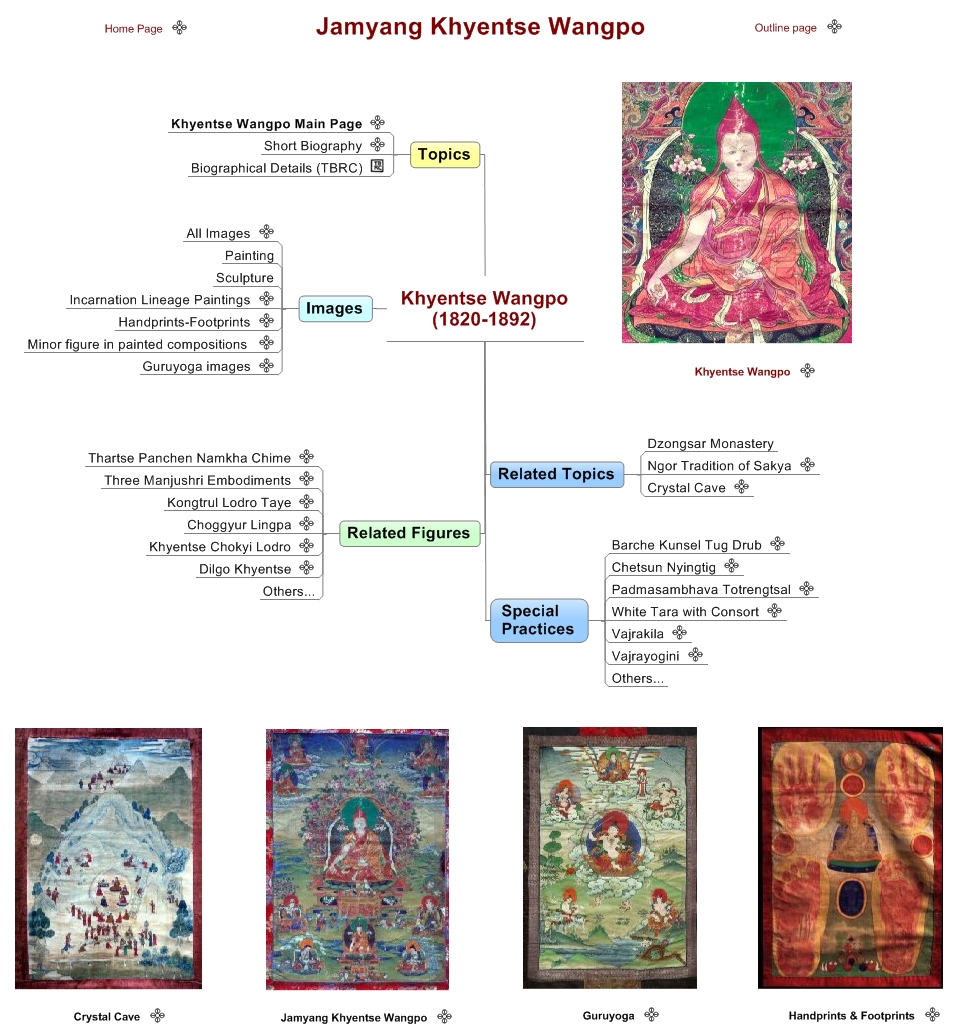

Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo (1820-1892) was one of the most exciting Tibetan Buddhist teachers of the 19th century. He was a prolific writer as well as inspiring others to write. Khyentse Wangpo along with Jamgon Kongtrul, Choggyur Lingpa, Loter Wangpo and others produced 100s of volumes of texts on all subjects related to Buddhism, history, art and Tibetan culture in general.

Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo (1820-1892) was one of the most exciting Tibetan Buddhist teachers of the 19th century. He was a prolific writer as well as inspiring others to write. Khyentse Wangpo along with Jamgon Kongtrul, Choggyur Lingpa, Loter Wangpo and others produced 100s of volumes of texts on all subjects related to Buddhism, history, art and Tibetan culture in general.