Amulet Box (Ga'u) Outline Page

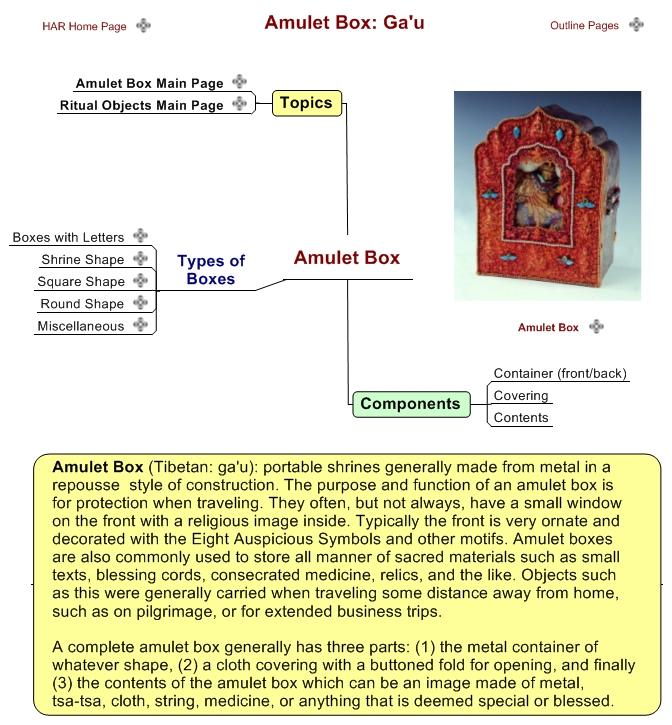

A new Amulet Box Outline Page has been added to the Amulet Box Main Page. The outline is divided into the five types of boxes and the three components.

A new Amulet Box Outline Page has been added to the Amulet Box Main Page. The outline is divided into the five types of boxes and the three components.

A new Amulet Box Outline Page has been added to the Amulet Box Main Page. The outline is divided into the five types of boxes and the three components.

A new Amulet Box Outline Page has been added to the Amulet Box Main Page. The outline is divided into the five types of boxes and the three components.

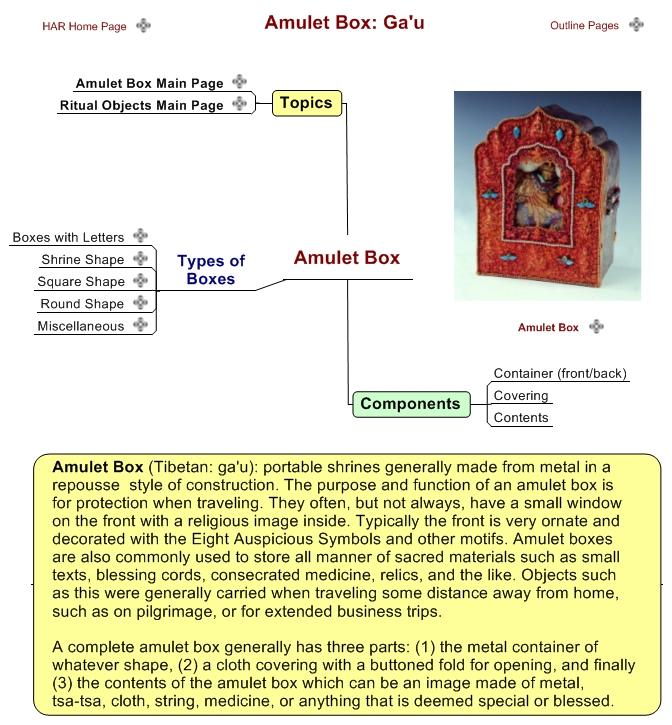

A Figurative Art Outline Page has been added to the Art History Main Page. It is divieded into the (1) Three Moods, (2) Catagories of Human Figures and (3) List of Appearance Type with Name.

A Figurative Art Outline Page has been added to the Art History Main Page. It is divieded into the (1) Three Moods, (2) Catagories of Human Figures and (3) List of Appearance Type with Name.

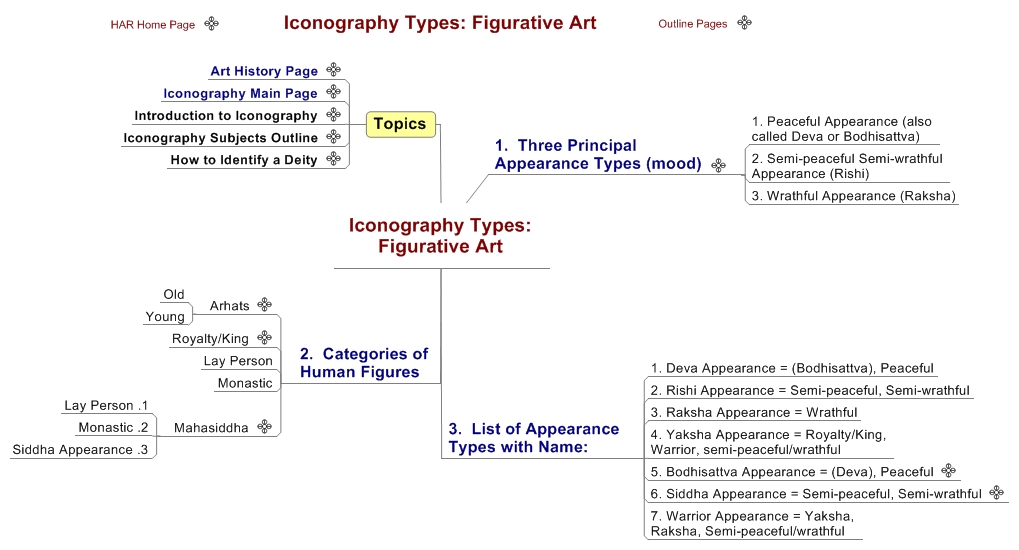

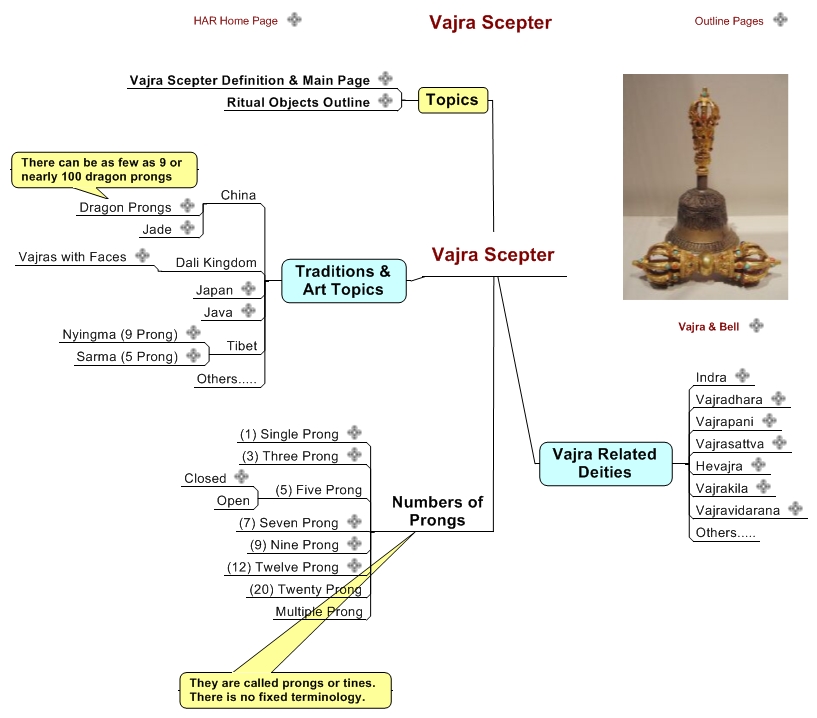

A Vajra Outline Page has been added to the Vajra Scepter Main Page. The amount of information on the outline page is far less than that on the definition page. However, the outline page does list clearly at a glance the most important visual characteristics of vajras, differences, the two most common Tibetan types (5 & 9 prong), and the other cultural traditions that employ vajras.

A Vajra Outline Page has been added to the Vajra Scepter Main Page. The amount of information on the outline page is far less than that on the definition page. However, the outline page does list clearly at a glance the most important visual characteristics of vajras, differences, the two most common Tibetan types (5 & 9 prong), and the other cultural traditions that employ vajras.

Amulet Box (Tibetan: ga'u): Amulet Box (Tibetan: ga'u): portable shrines generally made from metal in a repousse style of construction. The purpose and function of an amulet box is for protection when traveling. They often, but not always, have a small window on the front with a religious image inside. Typically the front is very ornate and decorated with the Eight Auspicious Symbols and other motifs. Amulet boxes are also commonly used to store all manner of sacred materials such as small texts, blessing cords, consecrated medicine, relics, and the like. Objects such as this were generally carried when traveling some distance away from home, such as on pilgrimage, or for extended business trips.

Amulet boxes are made in different shapes and sizes. They can be divided into several basic categories:

(1) Boxes with Letters

(2) Shrine Shape

(3) Square Shape

(4) Round Shape

(5) Miscellaneous

Vajra Scepter (Tibetan: dor je. English: the best stone): [1] from the Vedic literature, the scepter of the Hindu god Indra namely a lightening bolt, [2] from the Puranic literature, a weapon made from the bones of a rishi, and [3] a word that is used to represent Tantric Buddhism - Vajrayana. As a Buddhist scepter it is a small object made of metal generally having five or nine prongs at each end that bend inward to form a rounded enclosure. As a ritual object in Tantric Buddhism it is usually accompanied by a bell with a half vajra handle (Sanskrit: ghanta). Vajras are also found with Buddhists of South-east Asia, particularly Java, and with the Shingon Buddhists of Japan.

The nine pronged configuration is the vajra most commonly used by the Nyingma Tradition of Tibetan and Himalayan Buddhism. The five pronged configuration is the vajra used by the new schools, or Sarma Traditions: Sakya, Kagyu, Jonang, Gelug, etc.

A one pronged vajra is related to naga rituals. A vajra with five prongs having the tines or tips open and not touching the central prong is a 'wrathful' five prong vajra. Vajras with faces adorning the center are thought to be created in the Dali Kingdom of South-west China. Vajras with dragon prongs of nine or more, some over one hundred, are of Chinese origin. Vishvavajras with twenty prongs represent activity and are typically held in the hand of the deity Vajravidarana or the Buddha Amoghasiddhi.

There are many types and variations of vajras:

1. Single Pronged Vajra

2. Three Pronged Vajra

3. Five Pronged Vajra - closed tines

4. Five Pronged Vajra - open tines (wrathful)

5. Seven Prong Vajra

6. Nine Pronged Vajra

7. Twelve Pronged Vajra (vishvavajra)

8. Twenty Pronged Vajra (vishvavajra)

9. Multiple Pronged Vajra

10. Vajras with Faces (Dali Kingdom?)

11. Vajras with Dragon Prongs

12. Japanese Vajras

13. Javanese Vajras

14. Dali Kingdom Vajras

15. Jade Vajra & Bell

It is now October and most schools, colleges and universities have been in session for at least a month. It is time again to remind educators to submit requests to the HAR Team. Is there a particular area of study where we are not providing enough information? Is there an Outline Page or Thematic Subject Set not fully represented - an area completely missed? Let us know your needs so that we can prioritize our work with you and the students in mind. Contact us at info@himalayanart.org. (About Us page and view a list of educators that use the HAR website).

Yes, Himalayan Art Resources (HAR) can be found on Facebook. Some visitors to HAR prefer to make comments on the Facebook page rather than on the HAR News page. Either or, we are happy to have the comments.

Aniko, originally known as Barub (or Balabahu), 1244-1306, is said to have been born in a Nepalese royal household descended from the Shakya family of Lumbhini and the historical Buddha - Shakyamuni. The name Aniko is said to come from the name Araniko given to him by Chogyal Pagpa, a name in some way thought to be related to the protector deity Panjarnata Mahakala. Between 1259 and 1264 eighty craftsmen and artists journeyed from the Kathmandu Valley to Sakya, Tibet, to construct a golden stupa. Aniko was the leader of the group. After recieving monastic ordination, in 1269 Aniko traveled with Chogyal Pagpa to Dadu (Beijing) to meet with Kublai Khan. In 1271 Aniko began constructing the White Stupa 'for the preservation of the country'. In 1274 it was filled and consecrated by Chogyal Pagpa and Rinchen Gyaltsen - the brother of Pagpa. On October 25th, 1279, the stupa was officially completed. After completion a monastery was immediately built around the stupa. After ten years the temple and monastery were finished and named Dashengshou Wan'an Monastery becoming the principal place of Buddhist worship for the Mongol Lords.

Aniko was also renowned for constructing other buildings and monasteries under the command of Kublai along with 191 statues of Taoist saints. In 1302 the famous White Stupa of Mount Wutaishan, special for Manjushri, was also constructed by Aniko on top of and around an existing famous pagoda built centuries earlier. Chogyal Pagpa is also said to have contributed to the physical labour of the construction and to first associate the five peaks, or terraces, with the Five Forms of Manjushri. Of the 40 years that Aniko spent in China 13 of those years were at Wutaishan Mountain. Aniko passed away at the age of 62 in the Imperial Palace in Dadu.

Aniko is primarily remembered for his architectural achievements and for the creation of sculpture objects. A painting of the Emperor and Empress have been attributed to him in the literary records. The two known remaining works are the White Stupa in Beijing and the Stupa at Wutaishan Mountain. Modern scholars are not in agreement concerning any other monuments, paintings or sculpture. (See article on Araniko Gallery).

This Vajravarahi sculpture, for its time and type, is surely one of the finest ever created. Also view the five detail images. The face is beautiful although likely re-painted in the recent past. The body proportions and movement are excellent. The ornamentation is precise and detailed, also textually accurate. The elaborate scarf (not part of the textual description) is beautifully excessive with studded semi-precious stones - likely original to the piece - framing the central figure and bringing the entire sculpture to a fullness that is greater than the sum of the parts. Sculptural perfection - art and iconography!

The depicted forms and ritual practices of Medicine Buddha (Bhaishajyaguru) are derived from the Bhaishajyaguru Sutra and according to Buddhist Tradition were taught by Shakyamuni Buddha. In the Vajrayana Buddhist Tradition this sutra is classified as Tantra literature and belonging to the Kriya classification. Many works under the Kriya classification are understood as being both sutra texts and tantra texts at the same time. Medicine Buddha imagery and practice is common to all of Tibetan and Himalayan Buddhism and particularly important to the Tibetan medical schools and traditions.

Medicine Buddha can be placed in a number of different compositions in painting and sculpture. He can be depicted alone or with his seven accompanying Buddhas (included is Shakyamuni - known as the Eight Medicine Buddha Brothers [Block Print Set]). Bhaishajyaguru can be depicted at the center of a Fifty-one Deity Mandala (see list of deity figures), or he can be relegated to a side position while the female personification of wisdom, Prajnaparamita, occupies the central position of the Medicine Buddha mandala. Sets of paintings can be commissioned depicting the Eight Medicine Buddha Brothers, or sets of paintings can be created depicting each of the fifty-one deities in their own composition. Often these sets are done with the painted canvas relatively small. In China they are commonly created as embroidered sets. They are then strung together and hung as a complete set in a temple or meeting hall. Likewise, sets of sculpture composed of fifty-one figures were also created and then arranged on a temple shrine. Many of the figures making up the fifty-one deities, when viewed individually and out of context with the whole, are often mis-identified and mistaken for other deities. The Twelve Yakshas Generals in the outer ring of the Medicine Buddha Mandala are most often mistakenly identified as forms of Jambhala, or even the more erroneous Kubera. (See Medicine Buddha Outline Page).

Description: The Guru of Medicine (Sanskrit: Bhaishajyaguru) is also known by the name Vaidurya Prabha Raja, the 'King of Sapphire Light.' Dark blue in colour, with one face and two hands he holds in the right hand a myrobalan fruit (Latin: terminalia chebula. Skt.: haritaki). The left hand is placed in the lap in the gesture of meditation supporting a begging bowl with the open palm. Adorned with the orange and yellow patchwork robes of a fully ordained monk, the left arm covered, he appears in the nirmanakaya aspect of a fully enlightened buddha. In vajra posture above a moon disc, he sits on a lotus and ornate lion supported throne with a back rest. At each side of Medicine Buddha stand the two principal bodhisattva attendants. To the left is the yellow bodhisattva Suryabhaskara (Rays of the Sun) and to the right is white Chandrabhaskara (Rays of the Moon).

Related Subjects:

Yutog Yontan Gonpo

Yutog Nyingtig

Padmasambhava as Medicine Buddha

Medical Charts: Blue Beryl

Medicine & Tantric Healing

Virupa and Kanha (Tibetan: nal jor wang chug bir wa pa. Nag po pa shar chog pa). This painting, number two in a series of lineage compositions, belongs to a larger set of paintings depicting the lineage of teachers for the Path together with the Result (Sanskrit: margapala. Tibetan: Lamdre) teaching originating with the mahasiddha Virupa. The Indian adept of the 9/10th century, Virupa,had two main students, Kanha and Dombhi Heruka. Virupa taught both of them the Lamdre (Margapala) system, The Path Together with the Result, based significantly but not exclusively on the Hevajra Tantra. Kanha, meaning black, was the principal student in the Lamdre lineage following after Virupa. In Western texts and Tibetan translated material this and similar names can appear in Sanskrit as Kanha, Kanhapa, Kanhavajra, Krishna, Krishnapa, Krishnavajra, Krishnacharin, Krishnacharya and Kala Virupa. All of these terms are Sanskrit and relate essentially to the colour black. The Tibetan word for Kanha as a persons name is 'nag po pa' which means the 'black one.'

There are two very popular and well documented systems of listing the names and biographies of the Eighty-four Great Mahasiddhas of India. They are the Vajrasana and the Abhayadatta systems. Both of these were translated into the Tibetan language. Also, in both of these systerms there are several siddhas with the name Nagpopa along with various associated spellings.

Why is this important and why does it matter? It matters because there is another mahasiddha with the Sanskrit name of Krishnacharin (Nagpopa Chopa, or Nagpo Chopa) associated with the Chakrasamvara Cycle of Tantras. His name is also translated into Tibetan as Nagpopa. Here arises the confusion. Like the Indian siddha of the Lamdre lineage, Kanha, this other siddha, Krishnacharin is very important and more well known to a greater number of Tibetan Buddhist Tantric Traditions. This second siddha, Krishnacharin, is also represented in both the Vajrasana and Abhayadatta Systems of the Eighty-four Mahasiddhas. Kanha, also known as Kanha of the East, of the Sakya Lamdre Lineage is found only in the Vajrasana System.

Both of these siddhas, Kanha and Krishnacharin, have their own stories and unique hagiographies. For the purposes of Art History, Iconography and Religious Studies it is important to be able to name and differentiate the various siddhas and teachers in the important lineages that appear in the registers of paintings and wall murals. That is why this subject of the two 'Nagpopas' is important.

How do we know what to call these siddhas? Basically we can only rely on common convention over time. However, we do have early writings from teachers such as Chogyal Pagpa where he refers to the 'black' student of Virupa as 'Kanha' using the Sanskrit term. This is how we know that there is early precedent in the Sakya Tradition for distinguishing between these two 'black ones,' Kanha and Krishna. There is less confusion generally with Krishnacharin because he is represented in all of the New Schools of Tibetan Buddhism and associated so strongly with the Chakrasamvara Tantra traditions. He also has a very lively and interesting biography (hagiography). So, it is really only the Lamdre Lineage siddha by the name of Nagpopa (Kanha) that has become confused. This is because essentially he is only known in the Sakya Lamdre Tradition and the subsequent Pagmodrupa Lineage of Lamdre. In general there are many different lineages of Hevajra descending from Indian roots and many different siddhas. Whereas in the Chakrasamvara system Krishnacharin is prominent and very well known.

For individuals and scholars interested in this subject ultimately what is important is to know that there are two different mahasiddha figures with names that have often been used interchangeably. This has not been a Tibetan problem. In the Tibetan language the two siddhas are very clearly distinguished as Nagpopa (Kanha) and Nagpo Chopa (Krishnacharin). This is a modern Western academic problem in reading the Tibetan translated names for the early Indian Teachers and then interpreting what the original Sanskrit word and spelling would be and then back translating.

In conclusion, there are two Indian siddhas with similar Tibetan names one belongs to the Lamdre Lineage (Kanha) and the other belongs to the Chakrasamava Lineage (Krishnacharin).

In the Tibetan Buddhist tradition the deification of living teachers began with Padmasambhava and the early pairing with Amitabha Buddha and the deity Avalokiteshvara. In the Nyingma Tradition he is known as the 2nd Buddha of this age. Artistic representaions reflecting this change begin to appear as early as the 13th to 15th centuries (click on the dates for examples).

The Gyalwa Karmapa is another interesting Tibetan teacher, unlike Padmasambhava, the Karmapas are understood as the first incarnation lineage of Tibet beginning in the 12th century and continuing up to the present day (the 17th incarnation). The painting on the left is very interesting because it is the oldest composition known (16th century) depicting three depictions of Karmapa, appearing in ordinary form, but representing the highest spiritual states in Buddhism according to the written inscriptions accompanying each.

In the top register are three Karmapas that are not meant to represent any living Karmapa. These three represent the three Buddha bodies. Reading the painting from left to right are the (1) Buddha Karmapa representing the Dharmakaya, (2) Vidyadhara Karmapa representing the Sambhogakaya and (3) Mahasiddha Karmapa representing the Nirmanakaya. Below that, in the second register the 1st and 2nd Karmapas are depicted, along with name inscriptions, continuing down to the 8th Karmapa, Mikyo Dorje.

The name Rahula belongs to three important figures in Buddhist iconography. The (1) first use is as the proper name for the biological son, Rahula, of Gautama Siddharta - Shakyamuni Buddha. The (2) second use of the name is for the Indian cosmological deity Rahula, the deification of the phenomenon of an eclipse. The (3) third use of Rahula is for the horrific Nyingma protector deity, wrathful, with nine heads and a giant face on the belly. It is likely that this Buddhist protector is a Tibetan creation and not linked to any Sanskrit literature or Indian religious tradition. Aside from these three uses of the name there were also numerous Indian pandits and siddhas with the name Rahula, Rahula Bhadra, Rahula Gupta, etc.

Rahula (Tibetan: kyab jug): wrathful protector of the Revealed Treasure Tradition of the Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism. The Tibetan protector deity is based on the Indian deity Rahula, an ancient Indian god, a demi-god, of the cosmos, related to the eclipse of the sun, moon and other planets. In the ancient tradition of Tibetan Buddhism (Nyingma) Rahula became popular as a protector of the 'revealed treasure' teachings (terma). In Buddhist depictions he is portrayed with the lower body of a coiled serpent spirit (naga) and the upper body with four arms, nine heads, adorned with a thousand eyes. In the middle of the stomach is one large wrathful face. The face in the stomach, belly, is actually the face and head of Rahula. The nine stacked heads depicted above are the nine planets that Rahula has eclipsed, or rather literally swallowed, eaten and now symbolically appear on top of his own face and insatiable mouth. At the crown of the stack of all the heads is the head of a black raven.

"From a fierce E [syllable] in a realm equal to space, the Lord arises out of wrathful activity, smoky, with nine heads, four hands and a thousand blazing eyes; homage to the Great Rahula - Protector of the Teachings." (Nyingma liturgical verse).

There are numerous forms of the protector Rahula. Generally he will always have the nine heads and naga lower body. Sometimes the faces are all black in colour and at other times the faces can appear in different colours depending on the specific 'Revealed Treasure' literature describing a special form. There are also differences in the retinue figures again depending on the Terton (Revealer) and the descriptive literature.

In Tibetan and Himalayan Buddhism the ornately displayed throne-back, Torana, is known as the 'six ornament' design. The general shape is like an oval gate or frame, sometimes rectangular. On each side of the torana, at the bottom left and right are elephants. Supported above that are lions (or snow lions), a horse (often with the characteristics of other animals such as a lion, etc.). Above that is a small boy who sometimes holds a conch shell in one hand and supports a horizontal throne cross beam with the other. Above that is a makara (water creature). Above that is a naga - with a human upper torso and snake's tail for the bottom which extends upward. At the very top is a single garuda bird who often bites down with the beak on the two extended tails of the two nagas from below, or bites down on a naga held in the outstretched arms. Sometimes there is an ornate silk canopy above the torana. It is not clear how the various elements of the torana are enumerated into the group of the 'six ornaments.' It is possible that the boy and the flying horse are grouped as one ornament.

Top Down:

Garuda,

Nagas,

Makaras (water monster)

Boys,

Horses (sharabha, half lion),

Lions, and

Elephants.

Symbolically the 'six ornaments' have many Buddhist meanings such "as the seven things to be eliminated on the path, the six perfections, the four gathering things, the strength of the ten powers, the stainless and the clear light." (Gateway to the Temple by Thubten Legshay Gyatsho. 1971, 1979. page 46).

In the Bon Religion there is also a unique throne back (Tibetan: gyab yol) which is described for the special figure of Nampar Gyalwa a form of Tonpa Shenrab, founder of the Bon religion. This throne back is different from the Buddhist description most notably because in the Bon depiction the lion at the bottom of the throne back is eating a human figure and above that the winged-lion-horse (dragon) is eating a serpent spirit (lu). Although specific to the biography of Tonpa Shenrab in his form as Nampar Gyalwa this throne back is also commonly found with the Four Transcendent Lords, the suprreme deities of Bon, and depicted in both painting and sculpture. According to the biographical literature the animals should be a lion, dragon and water monster. This is described in detail in the story of Nampar Gyalwa found in chapter 50 of the Ziji a twelve volume biography of Tonpa Shenrab.

The Sarasvati Main Page has been updated with additional images and a list of the more common forms of Sarasvati depicted in Himalayan art. (Also see the Sarasvati Outline Page).

Ochen Barma 'Blazing with Great Light.' This fierce female deity, classified under the category of Shri Devi (Palden Lhamo), is the wrathful protector aspect of Vajra Vetali the consort of the awesome meditational deity (ishtadevata) Vajrabhairava. Ochen Barma is also an emanation, or wrathful form, of the very peaceful deity Sarasvati, Goddess of Learning, eloquence and literature.

The Three Forms of Sarasvati According to the Vajrabhairava System of Tantra:

1. Vajra Vetali, the female consort in wrathful aspect embracing Vajrabhairava. 2. Sarasvati, the peaceful aspect. 3. Ochen Barma (Blazing with Light) the protector aspect of Vajra Vetali.

Ochen Barma is wrathful in appearance, black in colour with one face and two arms. The yellow hair blazes upwards. In the upraised right hand she holds a staff and a butcher's stick. In the lowered left hand she holds a bag of disease and a lasso. With the right leg bent and the left straight above two prone figures, naked, black in colour, she stands atop a sun disc, lotus and dharmakara - triangle. The flames surrounding her body unfold like a peacock's tail.

There are twelve attendant figures accompanying Ochen Barma. The three most important of those ride animal mounts: horse, mule and wolf.

At the top center is Acharya Bhati. The seated figure at the viewer's right is Manlung Guru of the 13th century. He was a contemporary of Buton Tamche Khyenpa and associated with the Kalachakra Tantra. At the viewer's left is Dranton Dar Drag. The three teachers depicted each pre-date the 13th century and are identified by a name inscription beneath.

Black ground paintings such as this are often used for depicting the most wrathful and horrific images of Tantric Buddhism believing that it enhances those fearsome characteristics of the deity. The creation of black ground paintings was first described in the various Mahakala Tantras (specifically the Twenty-five and Fifty Chapter Tantras). The painting of Ochen Barma is likely from a set of compositions and currently of an unknown number. Only two other images of this rarely seen deity are known to the HAR Team - both minor figures. One image is depicted as a minor figure in a textile tangka preserved in the Palace Museum, Beijing. The other is a painting belonging to a private collection. It was this latter painting depicting Vajrabhairava as the central figure that provided the identification of Ochen Barma by depicting the exact deity and retinue, along with inscriptions, matching the image of the painting HAR #576.

(This painting was formerly incorrectly identified as a form of Ekajati and associated with Shri Devi. It is important to remember that Shri Devi Magzor Gyalmo is also a wrathful protector emanation of Sarasvati). [See TBRC W27414. The Tensrung Gyatso Namtar (bstan srung gya mtsho'i rnam thar) written by Lelung (sle lung)].

The Nepalese Legacy in Tibetan Painting.

September 3, 2010 - May 23, 2011. Rubin Museum of Art, New York.

"For centuries Tibetan artists looked to India for artistic direction. But with the destruction of India's key monasteries in 1203, many artists turned to Nepal's Kathmandu Valley, home to the skilled Newar artists. The Newars' painting style, known as the Beri, was quickly adopted in Tibet, becoming one of the country's most influential artistic styles for four centuries. This exhibition traces the style's development, patronage, and distinctive features." (RMA Website. Read a longer description).

See a selection of objects from the exhibition on the HAR Website.

This painting is iconographically unique because it is the only known composition depicting Vira Vajradharma as a central figure and the only painting known that depicts the two figures of Vajradhara and Vajradharma paired together in a single composition. Vajradharma originates with the Chakrasamvara cycle of Anuttaryoga Tantras and is another form of the Tantric Buddhist primordial Buddha. Vajradharma is red in colour and has two different iconographic forms. The first form, shown in this painting is considered common, Vira Vajradharma, and the second form is regarded as more profound, or uncommon. The second form does not use the initial term 'vira' meaning 'hero' (referring to the appearance of Vira Vajradharma with hand drum and skullcup) and simply goes by the name Vajradharma. The profound form of the primordial Buddha Vajradharma has the same identical appearance as Vajradhara except Vajradharma is red in colour rather than blue. (The primordial Buddha Vajradharma should not be confused with the red form of Avalokiteshvara also with the name Vajradharma [see image])

Unique Iconographic Features:

1. Vira Vajradharma (red) as a central figure.

2. The group of three Vajrayogini figures: Naro, Indra & Maitri.

3. The group of three power deities: Kurukulla, Takkiraja & Ganapati.

4. The inscriptions written on the cloth hangings in front of the two thrones - specifically the Kalachakra monogram.

5. The two Pamting brothers seated on the same lotus.

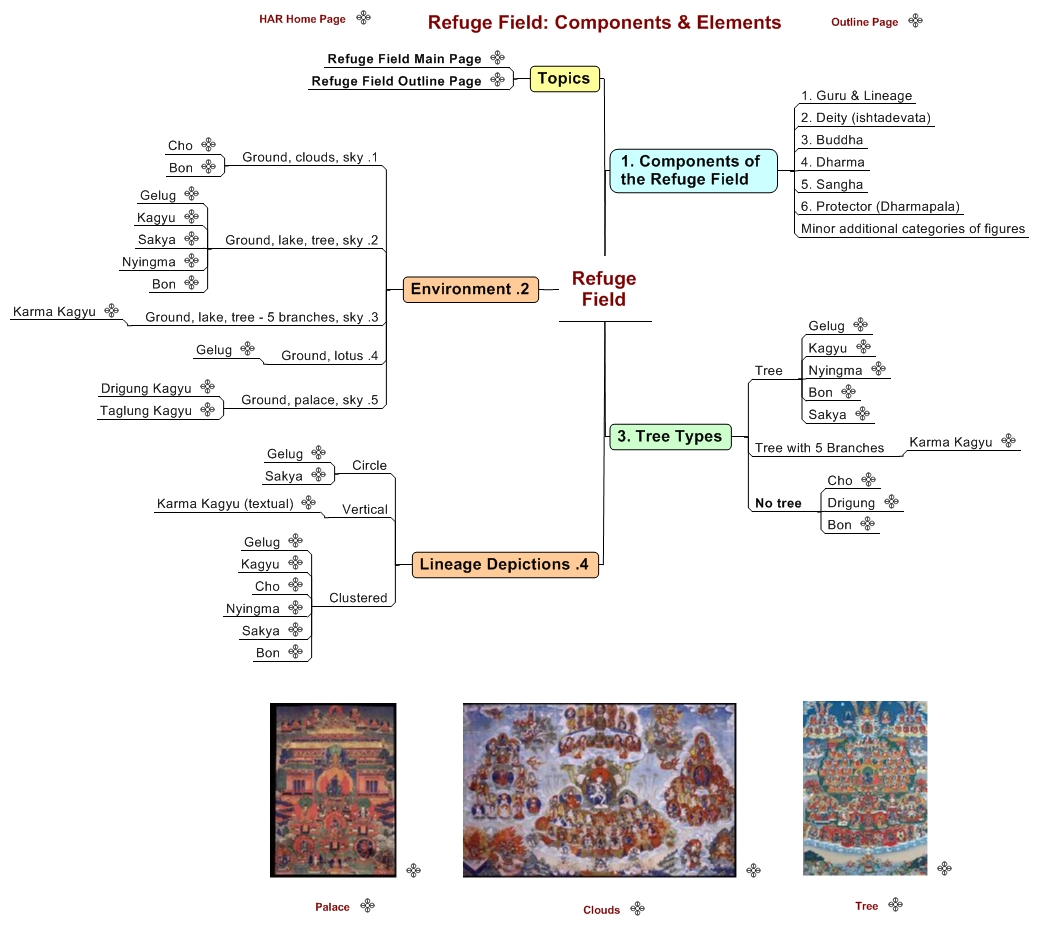

The various Components & Elements of Refuge Field paintings have been catagorized and listed in this new Outline Page. The topic is especially interesting because Refuge Field paintings are a relatively new art subject in Tibetan Buddhism. The two principal components of any Refuge Field painting are (1) the Environment (ground, lake, tree, throne, clouds, etc.) and (2) the actual Field of Accumulation (Refuge objects: Guru, lineage, Buddha, etc.).

The various Components & Elements of Refuge Field paintings have been catagorized and listed in this new Outline Page. The topic is especially interesting because Refuge Field paintings are a relatively new art subject in Tibetan Buddhism. The two principal components of any Refuge Field painting are (1) the Environment (ground, lake, tree, throne, clouds, etc.) and (2) the actual Field of Accumulation (Refuge objects: Guru, lineage, Buddha, etc.).

The earliest paintings depicting a Refuge Field belong to the Gelug tradition and clearly date to the 18th or possibly the late 17th century. Paintings following the iconographic programs of other religious traditions only begin to appear in the 19th century with paintings of the Longchen Nyingtig lineage of the Nyingma followed by Drugpa and Drigung Kagyu lineage depictions. All of the other Tibetan and Himalayan Buddhist lineages, schools and traditions, along with the Bon religion, only adopted the new Refuge Field composition in the early part of the 20th century with some traditions like the Sakya and the Nyingma (aside from the Longchen Nyingtig) only adopting the new composition style in the mid to late 20th century.

Links:

Refuge Field Main Page

Refuge Field Outline Page

Refuge Field: Components & Elements

An additional painting, HAR #66432, has been added to the Karmapa Masterworks Page on the HAR website. This painting is unusual because of the artist's individual style, the clarity of the various elements, rendering of figures, and the small narrative vignettes at the top right and left of the composition. The artist's name is currently unknown. Although the painting looks as if it should be a Karma Kagyu creation there are many elements in the details of the composition indicating that it is likely a Drugpa Kagyu painting done in honor of the 9th Karmapa. When more paintings from the complete set are found then the full iconographic program will be made clear.

Wangchug Dorje, the 9th Karmapa, (1555-1603), was a great traveler, scholar and practitioner, well educated and a moderately prolific writer. Two of his more important literary compositions on the philosophy of mahamudra were the 'Ocean of Certainty' and 'Eliminating the Darkness of Ignorance.' Amongst his many famous students was Jonang Taranata and other great masters of the time.

The central figure in the painting is identified as the 9th Karmapa, aside from the black hat, because of the right hand upraised in a gesture of blessing and the left hand holding a vase. The 9th Karmapa is generally depicted either in this manner or with the right hand extended across the knee and the left hand alternately holding a book in the lap. When looking at images of the sixteen Karmapas that appear in art, with general iconographic characteristics, no other from the fifteen has this consistent specific depiction, albeit with two variations.

The large central figure of Wangchug Dorje wears the typical black hat common to all recognized rebirths in the Karmapa incarnation lineage. He holds the right hand up to the heart in a gesture of blessing and the left hand in the lap holds a long-life vase. Wearing the red and orange robes of a fully ordained monk, he also wears an outer meditation cloak, gold and richly patterned. Karmapa sits on a cushioned throne with an ornate backrest of Chinese style with two dragon heads looking inwards at the seated figure. A large black lacquer table supports victuals and libations while again in front two more tables, pink and blue, present offerings, jewels and precious substances - real and imagined.

In the foreground, four attendant figures wearing monastic robes and red caps attend to the seated central figure of Karmapa. The attendant at the upper left offers a hat, large and fan-like, held with a white scarf. The attendant below offers tea from a round white teapot, held aloft, with a white scarf. The attendant at the upper right offers a Tibetan folio text, red and long, with a white scarf. The attendant below waves a metal censor, wafting incense, held by a gold chain in the right hand. The left hand holds a bag of precious incense in a striped woven cloth bag decorated with frills along the bottom.

Directly behind and above Karmapa is a tree trunk, with curved and knotty branches, tall, extending into the clouds, white, pink, yellow and blue, which pool to form a pond of blue water, rolling waves, with lotuses supporting a throne and pink lotus seat for the primordial Buddha Vajradhara, blue in colour. On the viewer's left is the Indian mahasiddha Tilopa and on the right side is Naropa - both are accompanied by an attendant figure - female.

Slightly lower than the top center, on the left side, is Marpa Chokyi Lodro and consort, Dagmema. Below that is the famous student of Milarepa, Gampopa Sonam Rinchen, wearing the robes of a monk and the hat which he designed. To the side of the throne sits Pagmodrupa - founder of the Eight Minor Kagyu Traditions (such as Drugpa Kagyu), slightly disheveled, balding and with a growth of facial hair.

Below Vajradhara on the right side is Milarepa, yogi and poet, student of Marpa, wearing the traditional white robes of a yogi and a red meditation belt, cupping his ear while singing to six figures seated in front. Below that is once again Pagmodrupa, with monastic robes, seated in a grass meditation hut, situated in a dense green forest.

Although this painting depicts a Karmapa as the central figure it is most likely a Drugpa Kagyu creation and part of a much larger composition. At this time the intention of the complete creation is not yet understood.

There are no apparent inscriptions on the front of the painting. There are however inscriptions on the verso but they were applied long after the painting was created. Some inscriptions are in a modern gold paint and others are written with a pen. Likely the inscriptions were applied by a former owner in the 20th century. Therefore, the inscriptions on the back are neither informative nor reliable.

This painting is the first composition in a set of paintings. We know this because at the back of the painting, top of the cloth mounting, there is the single Tibetan word 'tsowo.' This means 'main' or' principal.' It is the standard term written on the back of a painting to indicate which painting is number 'one' or the 'center piece' in a set. There is no way at this time to determine how many other paintings were in the complete set.