Reading a Painting: Example #1

This was first posted January 10th 2010 and fits well with these current posts on Reading a Painting.

This was first posted January 10th 2010 and fits well with these current posts on Reading a Painting.

Himalayan Art is a new area of study and in this study there are new tools and new ways to observe, approach and analyze the objects and works of art.

There are three important

fields of study that have to be brought together equally: (1)

Art History, (2) Iconography and (3) Religious Studies.

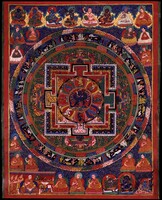

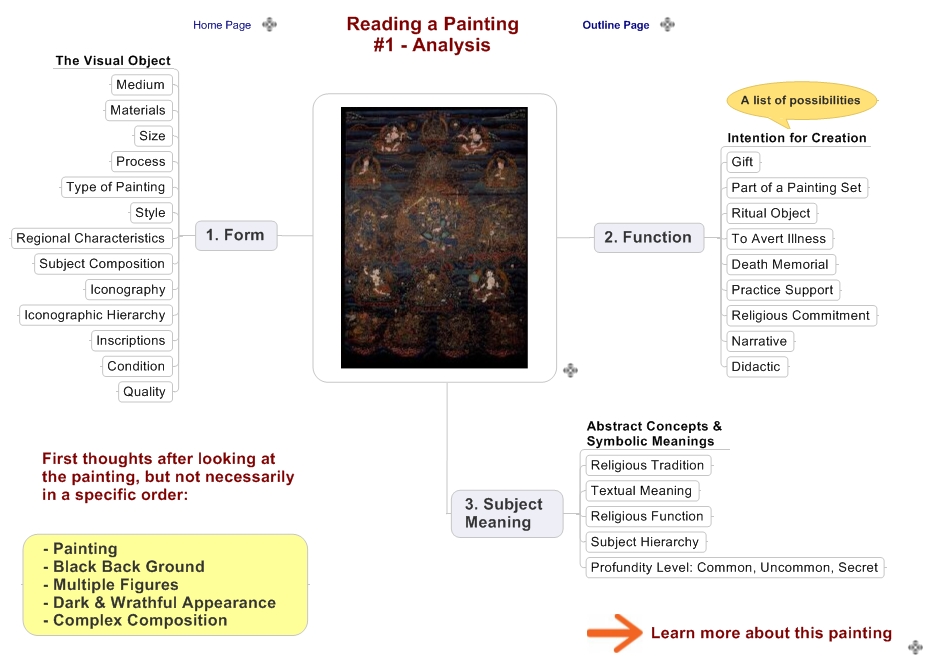

Because of the religious nature of the art and because of the living tradition that the objects are very much a part of there are three important points to observe when studying a Himalayan and Tibetan art object: (1) the Form - the physical object, (2) Function - the intention or purpose of creation and (3) Subject Meaning - the abstract concepts and symbolic meanings.

Following from the application of those three important points are (1) Analysis, (2) Interpretation and (3) Identification.

These pages for Reading a Painting are part of the on-going HAR project to create a Himalayan Art Curriculum and Study Guide. The image #113 (Chaturbhuja Mahakala) was chosen randomly based on a casual discussion with a museum guide. Paintings and sculpture covering a wider range of subject and type will be added in the future.