Detail Images of Chokyi Dorje of the Tibetan Lamrim Lineage

This subject page contains detail images of the Tibetan teacher Chokyi Dorje (15th century) included as a Lamrim Lineage teacher.

This subject page contains detail images of the Tibetan teacher Chokyi Dorje (15th century) included as a Lamrim Lineage teacher.

This subject page contains detail images of Vidyakokila the Younger an Indian teacher counted as one of the early Lamrim Teachers.

This subject page contains detail images of a currently unidentified early Indian Lamrim teacher. This composition is from a set of paintings depicting all of the Lamrim teachers of the Gelug Tradition. Currently only twelve of the paintings are accounted for from a total set of likely more than sixty individual compositions. The paintings themselves contain some of the finest artistic skill of the late 18th century.

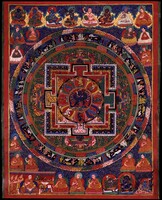

This composition of a mandala surrounded by smaller mandalas and an endless number of other figures looks impossibly complex and difficult to read. However, when the various sections are analyzed and separated they appear very organized, logical and understandable.

Follow the coloured sections: blue, red, green, purple, yellow and brown along with the lists of figures and see how this composition was constructed.

This subject page contains detail images of a Padmasambhava painting. The form of Padmasambhava is Pema Jungne from a nine composition set depicting the Eight Forms of Guru Rinpoche.

Surrounding the central figure are numerous narrative vignettes of the life story of Padmasambhava. At this time there are no other paintings from this set known in either private or museum collections.

At the middle right side are several depictions of Manjushri but the most interesting is the one with the five peaked, or terrace mountain, Wutaishan, in the background with five stupas marking each peak. Manjushri also holds a tortoise which is an important symbol in Buddhist astrology. Manjushri is believed to have invented astrology at Wutaishan Mountain.

This Bodhisattva Outline Page is a recreation of what a specific nine composition Eight Bodhisattva painting set would look like when complete. The images of the paintings represented here are from a number of different sets. Six partial sets are known to exist. The central image, likely to be that of Amitabha Buddha, is missing along with three of the eight bodhisattvas: Avalokiteshvara, Samantabhadra and Nivarana Vishkhambin. The six different sets all appear to follow the same compositional model. Stylistically they follow conventions that are more common with painting styles from the Kham region of Eastern Tibet. The correct order and position of each of the bodhisattvas is not yet determined.

This Bodhisattva Outline Page is a recreation of what a specific nine composition Eight Bodhisattva painting set would look like when complete. The images of the paintings represented here are from a number of different sets. Six partial sets are known to exist. The central image, likely to be that of Amitabha Buddha, is missing along with three of the eight bodhisattvas: Avalokiteshvara, Samantabhadra and Nivarana Vishkhambin. The six different sets all appear to follow the same compositional model. Stylistically they follow conventions that are more common with painting styles from the Kham region of Eastern Tibet. The correct order and position of each of the bodhisattvas is not yet determined.

Amitabha and Amitayus are the same person, or entity. In the Mahayana Tradition of Buddhism a buddha is described as having three bodies: a form body (nirmanakaya), an apparitional body (sambhogakaya) and an ultimate truth body (dharmakaya). The first, Amitabha, is the form body and the second, Amitayus, is the apparitional body. The ultimate truth body is without appearance and is generally not represented in painting or sculptural art.

The important iconographic difference in Tibetan art between the two, Amitabha and Amitayus, is that Amitabha has Buddha Appearance and Amitayus has Bodhisattva Appearance.

Amitayus, although commonly referred to in the Mahayana literature, is a very popular meditational deity in Vajrayana Buddhism. He belongs to the important and popular set known as the Three Long-life Deities: Amitayus, White Tara and Ushnishavijaya. There are also mandala practices such as the Nine Deity Mandala of Amitayus along with forms of the deity where he is embracing a consort.

Rechungpa, the famous student of Milarepa, recieved a special practice tradition of Buddha Amitayus from Tipu Pandita while on a trip to India. Upon his return he passed the tradition on to Milarepa. This is known as the Rechung Tradition. As a meditational practice in the lower tantras Amitayus primarily serves as a Long-life deity.

There are many different Buddhas represented in Buddhist art. Following after the many images of the historical Buddha Shakyamuni the next most common Buddha form to appear in art is likely to be Amitabha (immeasurable light). His popularity is based in the Mahayana Sutra literature of which there are many texts specifically devoted to him.

In art depictions Amitabha has two appearances and two names that differentiate those appearances. When referred to as Amitabha he has the appearance of a standard buddha form, although red in colour, wearing the traditional patchwork robes of a monk. In his other appearance he has a different name, Amitayus (immeasureable life), and wears the clothing and jeweled adornments of a peaceful heavenly god according to the classical Indian system of divine aesthetics.

In the Mahayana Tradition of Buddhism a buddha is described as having three bodies: a form body (nirmanakaya), an apparitional body (sambhogakaya) and an ultimate truth body (dharmakaya). Amitabha and Amitayus are the same person, the first is the form body and the second the apparitional body. The ultimate truth body is without description.

The important iconographic difference between the two, Amitabha and Amitayus, is that Amitabha has Buddha Appearance and Amitayus has Bodhisattva Appearance.

Forms & Iconography:

- As a solitary Buddha seated in front of a tree

- Seated in Sukhavati

- Seated in Sukhavati surrounded by the Eight Great Bodhisattvas

- Seated in Sukhavati surrounded by the Sixteen Great Bodhisattvas and other figures

- Surrounded by lineage teachers and/or various deities (artist & patrons choice)

- Amitabha included with the Five Symbolic Buddhas of the Tantra System

- Others...

An outline page for the Kundeling Tatsag Painting Set has been added.

An outline page for the Kundeling Tatsag Painting Set has been added.

This post was also first uploaded January 25th 2010.

This post was also first uploaded January 25th 2010.

View another example of How to Read a Painting #2.

This was first posted January 10th 2010 and fits well with these current posts on Reading a Painting.

This was first posted January 10th 2010 and fits well with these current posts on Reading a Painting.

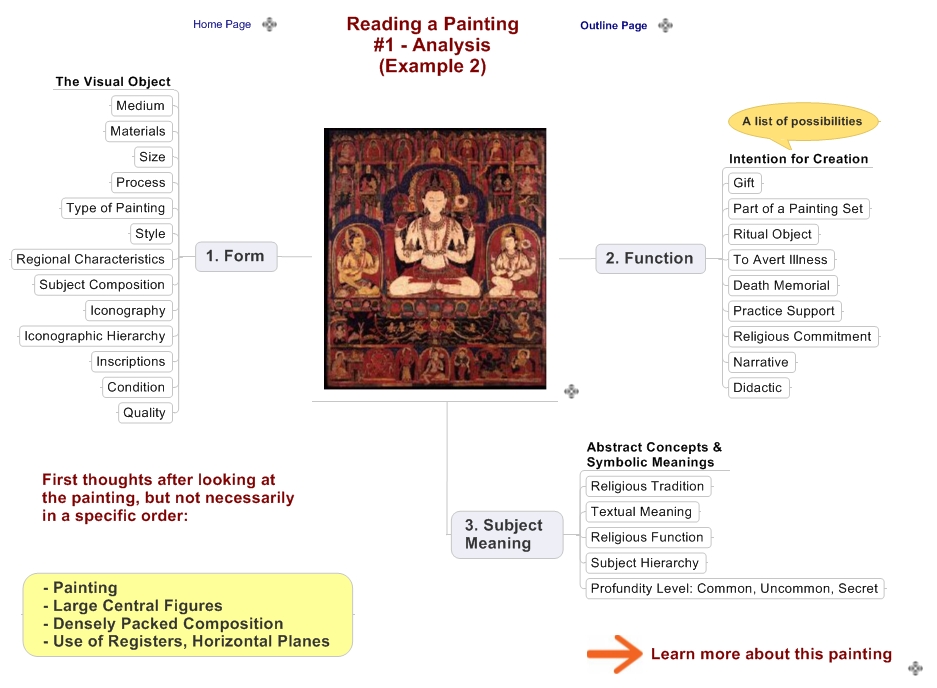

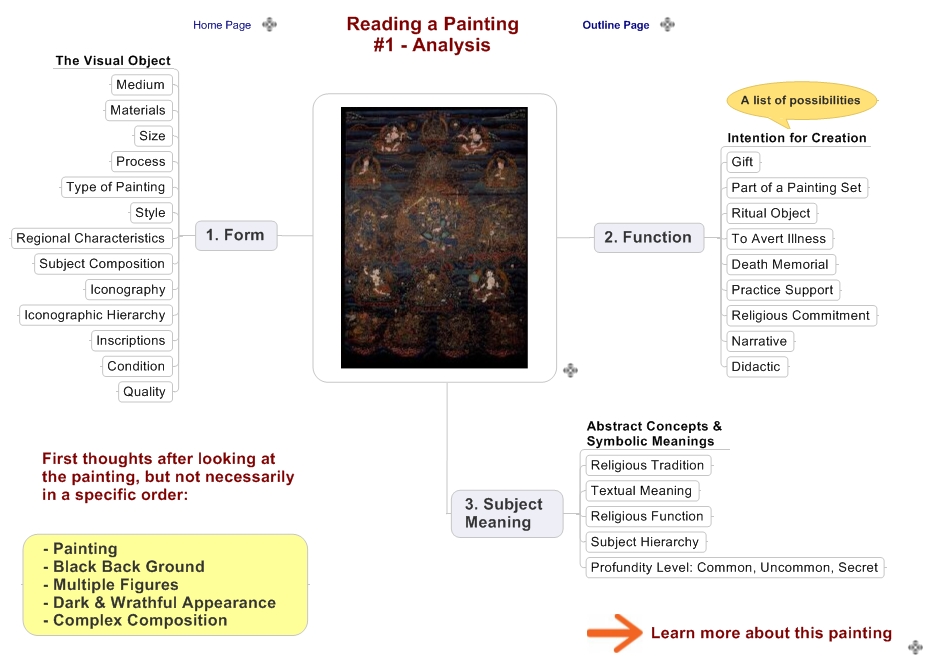

Himalayan Art is a new area of study and in this study there are new tools and new ways to observe, approach and analyze the objects and works of art.

There are three important

fields of study that have to be brought together equally: (1)

Art History, (2) Iconography and (3) Religious Studies.

Because of the religious nature of the art and because of the living tradition that the objects are very much a part of there are three important points to observe when studying a Himalayan and Tibetan art object: (1) the Form - the physical object, (2) Function - the intention or purpose of creation and (3) Subject Meaning - the abstract concepts and symbolic meanings.

Following from the application of those three important points are (1) Analysis, (2) Interpretation and (3) Identification.

These pages for Reading a Painting are part of the on-going HAR project to create a Himalayan Art Curriculum and Study Guide. The image #113 (Chaturbhuja Mahakala) was chosen randomly based on a casual discussion with a museum guide. Paintings and sculpture covering a wider range of subject and type will be added in the future.

There are four main types of lineage depiction in single composition paintings: [1] Standard Type A, [2] Standard Type B, [3] Two Lineages Type C and [4]. Asymmetrical Type D. These four types can be found in compositions with registers, common to early paintings and with compositions without registers common with the later paintings after the 15th century. From the 18th century to the present a new and additional compositional format was developed that included in a single painting the most significant teaching lineage of a given tradition along with all of the principal meditational deities, special deities and protectors, both general and unique. This compositional format is known as a Field of Accumulation, in brief a Refuge Field painting.

1. In Standard Type A the lineage of teachers begins at the top left and proceeds to the right and then descends to a second or third horizontal register or proceeds to the vertical registers on the left and right side of the composition. Standard Type A is more commonly found in early paintings.

Examples with Registers:

Hevajra Mandala (Dzongpa)

Hevajra Mandala (Kagyu)

Avalokiteshvara

Kagyu Lineage Teachers

Sakya Lineage Teachers

Virupa, Mahasiddha

Kagyu Lineage Teachers

2. In Standard Type B the beginning of the lineage starts with a central figure in the top row of the top register, often Vajradhara or Shakyamuni Buddha and then alternates with the first teacher to the viewer's left and then the right and again to the left - alternating horizontally and then vertically descending down the left and right registers. This Type B is more commonly found with paintings after the 15th century up to the present.

Examples with Registers:

Hevajra Mandala

Krodha Vajrapani

Examples without Registers:

Guru Dragpo

Avalokiteshvara

Kagyu Lineage Teacher

3. In Standard Type C the beginning figure, as in Type B, is in the top central position with one unique lineage of teachers (figures) placed to the left and then descending down the vertical register and a second unique lineage of teachers placed to the right and then descending down the right register. Sometimes, depending on the length of the lineage and number of teachers included, the central figure at the top may be moved slightly to the right of left side to accommodate an uneven number of figures calculated between the two unique lineages [see example].

Examples with Registers:

Vajradhara & Vajradharma

Mahasiddha Lineage Teachers

Examples without Registers:

Gelug Lineage Teachers

Gelug Lineage Teachers

4. In Asymmetrical Type D the top central figure is out of order and directly proceeds in chronological order the main central figure of the composition in the painting. The beginning of the lineage starts either immediately to the viewer's left of the top central figure or in the top left hand corner of the composition. This is generally only found when the central subject is a lineage teacher and not a Buddha, deity, or other such figure.

Examples with Registers:

Kagyu Lineage Teachers

Kagyu Lineage Teachers

Kagyu Lineage Teachers

This composition depicts a wrathful deity at the center of a painting with a multitude of smaller figures and architectural structures surrounding. Looking carefully at the 'find Waldo' style of composition the sections begin to come into focus and take on very clear meaning and purpose.

Paintngs such as this Avalokiteshvara with Eleven Faces and One Thousand Arms are read and understood first from the large central figure at the center of the painting. With multiple figure compositions incorporating a number of related or unrelated subjects then standard Buddhist hierarchy dictates that the Guru and Guru Lineage is at the top of the composition. The Guru is followed by Buddhas and Bodhisattvas.

In this painting a second Avalokiteshvara subject, comprised of five deities, has been added on the viewer's left side in the vertical outer register. Again related to Avalokiteshvara, a unique characteristic of this painting is found in the group of Eight Great Bodhisattvas where the standard figure of Avalokiteshvara is substituted for a non-standard but popular meditational form of the deity known as Simhanada. This was likely done by the artist to add variation rather than simply repeating the generic two armed form of the figure. Avalokiteshvara is already well represented at the center of the composition, the top left corner and then again as the first figure in the group of the Five Deity Amoghapasha. The Simhanada is added as variation - the next most popular form - although never typically seen in the group of Eight Great Bodhisattvas. The bodhisattva Maitreya is depicted twice once in the group of the Eight Great Bodhisattvas in the right hand register and then again on the upper left side placed amongst the Buddha figures. This figure of Maitreya represents the bodhisattva heir apparent - the future Buddha and is in close proximity to Dipamkara the Buddha of the past and Shakyamuni the Buddha of this time period.

Moving further down the composition two monk figures are located at the sides of the lotus throne of Avalokiteshvara. These two figures in the hierarchy represent the Arhats and Pratyekabuddhas of the Hinayana Tradition of Buddhism as understood in Himalayan and Tibetan Buddhism. They represent all arhats and all pratyekabuddhas.

On the lower right side are two deity figures unrelated to the general theme of Avalokiteshvara - the principal subject of the painting. They are Ushnishvijaya a Long-life meditational deity and Vajravidarana a purification meditational deity. These two figures and others of similar function are commonly found in the lower registers or portion of a painting. These types of function, long-life, purification and such, are often auxiliary meditational practices for removing various obstacles such as illness or various types of mental obscurations. Another class of deities with a specific function that are commonly found in the lower portions of a painting are wealth deities such as Jambhala, Vasudhara and Vaishravana. No wealth deities are depicted in this painting.

At the left side of the bottom register are three meditational deities that could easily be placed higher in the composition based on standard hierarchy. The first two are easily identified and the third is likely to be Vajrapani although not conclusively. Here Vajrapani is holding a vajra in the upraised right hand but also holds a long hook in the left hand. This is not standard for Vajrapani. The standing of the three figures in the standard hierarchy is that of meditational deity. Here their status is unchanged and they are placed next to the group of protector deities because they are the special meditational deities when performing the rituals and practices invoking the enlightened and unenlightened, wisdom and worldly, protectors - the last and lowest deities in the Buddhist Tantric hierarchy.

The Art Depicted in Art Main Page has been updated with additional images.

1. A rolled up painting in a meditation cave

2. A painting of the Sage of Long-life decorating a fan

3. A gold statue of Maitreya

4. A gold statue of Shakyamuni Buddha

Lamrim Lineage sets of paintings where each lineage figure is depicted in a single composition, surrounded by life story scenes, are quite rare. It is very common to find the Lamrim lineage all together in a single composition with Je Tsongkapa at the center. This set is by far one of the most beautiful known to exist. There are only twelve paintings known to exist that belong to this Lineage Set (Stages of the Path). The total number of paintings belonging to the original commission is currently unknown but would likely exceed more than fifty compositions in number. The majority of the paintings below belong to private collections with only two known to belong to a museum. (See the Lamrim Painting Set Outline Page).

Rubin Museum of Art:

Shantarakshita

Purbu Chog (student of Geleg Gyatso)

Dr. David Nalin Collection:

Namkha Gyalpo

Gendun Drub, 1st Dalai Lama

Yeshe Dorje

Unidentified

Private Collections:

Asanga (student of Maitreya)

Dromton (student of Atisha)

Unidentified (student of Acharya Vairochana)

Vidyakokila the Younger (student of Vidyakokila the Elder)

Chokyi Dorje, 15th century (student of Baso Chokyi Gyalstsen)

Geleg Gyatso, 16th/17th century (student of 1st Panchen)

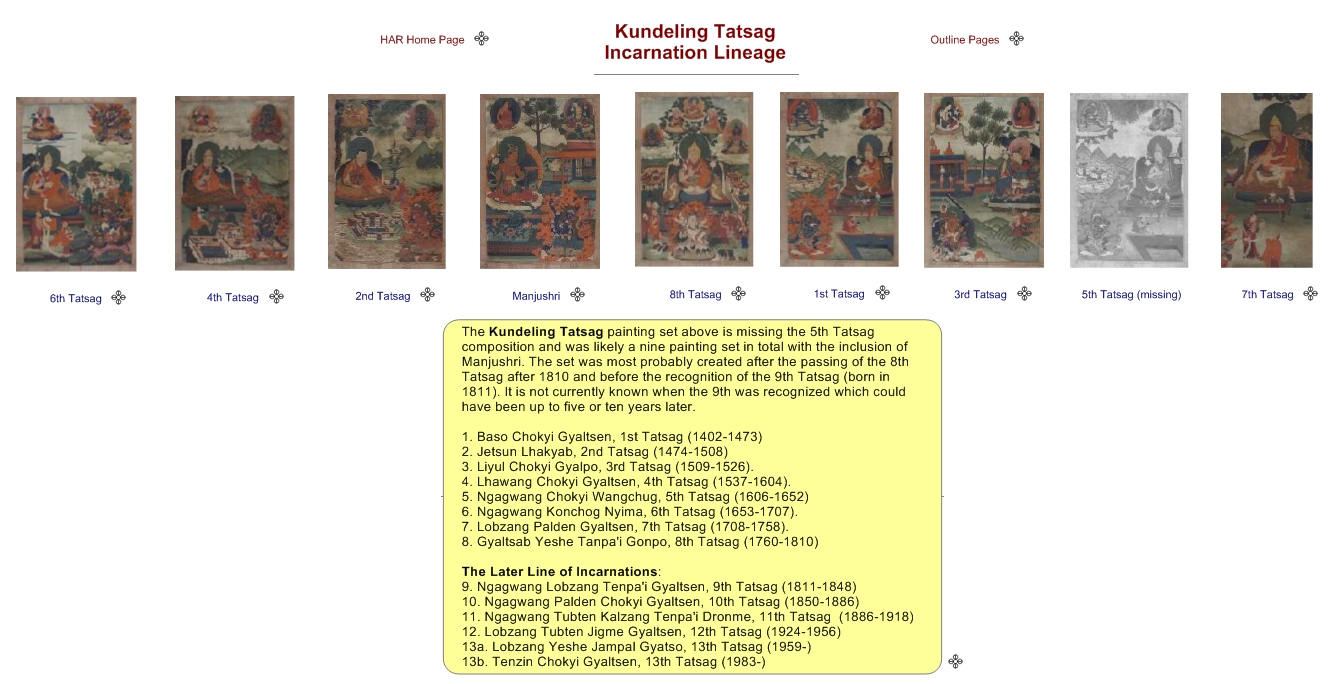

The Kundeling painting set is missing the 5th Tatsag composition and was likely a nine painting set in total with the inclusion of Manjushri. The set was most probably created after the passing of the 8th Tatsag after 1810 and before the recognition of the 9th Tatsag (born in 1811). It is not currently known in which year the 9th was recognized, but this could have been up to five or ten years later.

The composition and execution of the paintings in a Chamdo style follows very closely with other known paintings, both in private and museum collections, associated with the Chamdo region of Eastern Tibet.

1. Baso Chokyi Gyaltsen, 1st Tatsag (1402-1473)

2. Jetsun Lhakyab, 2nd Tatsag (1474-1508)

3. Liyul Chokyi Gyalpo, 3rd Tatsag (1509-1526).

4. Lhawang Chokyi Gyaltsen, 4th Tatsag (1537-1604).

5. Ngagwang Chokyi Wangchug, 5th Tatsag (1606-1652)

6. Ngagwang Konchog Nyima, 6th Tatsag (1653-1707).

7. Lobzang Palden Gyaltsen, 7th Tatsag (1708-1758).

8. Gyaltsab Yeshe Tanpa'i Gonpo, 8th Tatsag (1760-1810)

The Vaishravana Main Page has been updated with information and images.

There are three divisions in the study of Vaishravana iconography. The first, discussed above, is [1] Vaishravana as part of the group of Four Guardian or Direction Kings. These four are based on narrative descriptions found in the early Sutras. The second [2] classification of Vaishravana iconography is where the Four Guardian Kings are included in a larger retinue of a Tantric Mandala such as Medicine Buddha, Pancha Raksha or the Tara Seventeen Deity Mandala. The third division [3] contains all of the forms of Vaishravana as found in the Tantra literature where the deity is either the principal figure for meditation, or visualized in front of the Buddhist practitioner. These forms of Vaishravana generally have the function of wealth-bestowing. Vaishravana in his form known as Vaishravana Riding a Lion is the most common in art and most popular Tantric form of the deity. The Sakya Tradition preserve and teach seventeen different forms of Vaishravana (example 1, example 2).

The Twelve Yaksha Generals belong to the mandala of the Medicine Buddha. The full set of deities in the mandala number fifty-one paintings, textiles, or sculpture in total. The images of the Twelve Yaksha Generals below represent what remains of a number of different sets.

These figures are commonly misidentified as being forms of Jambhala, Vaishravana or the erroneously identified Kubera (who is not found in Himalayan and Tibetan iconography except as a minor figure in a few mandalas).

Twelve Yaksha Generals:

36 (1). Eastern direction, Jijig, yellow, vajra.

37 (2). Vajra, red, sword.

38 (3). rgyan 'dzin, yellow, stick.

39 (4). Northern direction, g.za' 'dzin, light blue, stick.

40 (5). rlung 'dzin (Vatadhara), red, trident.

41 (6). gnas bcas, smoky-coloured, sword. Example 2

42 (7). Western direction, dbang 'dzin, red, stick. Example 2

43 (8). btung 'dzin, yellow, stick.

44 (9). smra 'dzin, pink, axe.

45 (10). Southern direction, bsam 'dzin, yellow, lasso.

46 (11). g.yob 'dzin, blue, stick.

47 (12). rdzogs byed, red, wheel.

All hold a mongoose in the left hand, with short fat limbs and a large stomach.

Additional paintings and sculpture have been added to the Medicine Buddha Retinue Figure Page. The Medicine Buddha and his mandala of fifty-one deities was a very popular theme in Tibet and especially in China. Many sets were created of each of the individual figures with the paintings, or embroidered textile, created in a smaller format size and then strung together and hung from the rafters of temples. These smaller format compositions often had elaborate Chinese brocades and cloth mounts.

Included in the fifty-one figure mandala are Twelve Yaksha Generals that are commonly confused with the wealth deities Jambhala and Vaishravana because of their regal appearance, portly size, and the mongoose held in the left hand.