Buddha Appearance Outline Page - Added

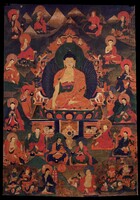

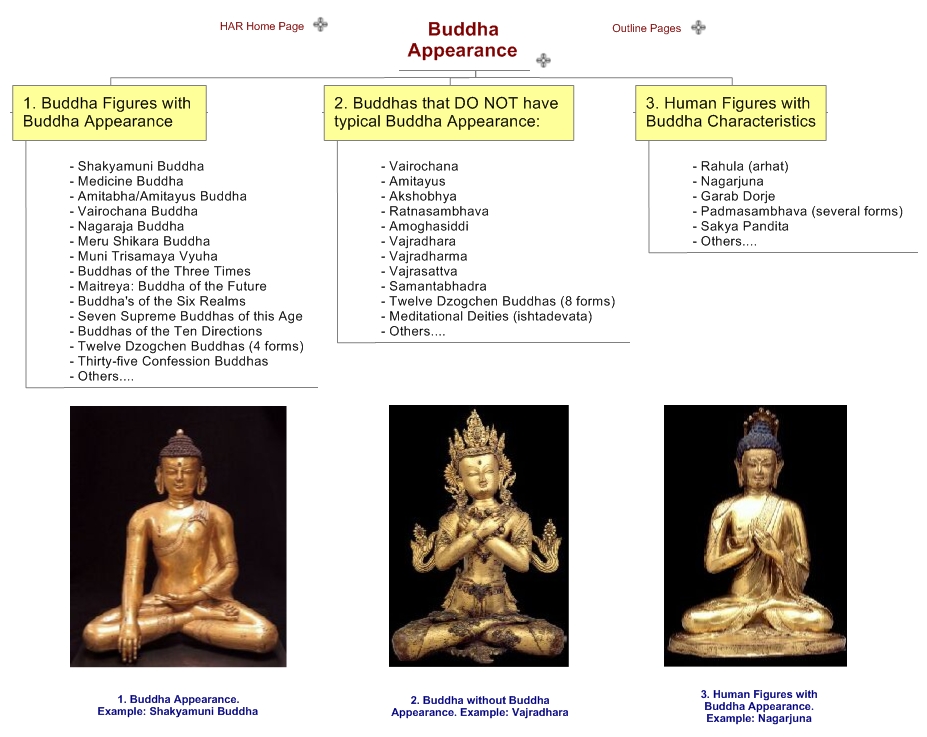

In art Buddha Appearance refers to figures that have the form of a buddha as defined by the early Buddhist literature describing the characteristics of a buddha such as the Thirty-two Major and Eighty Minor Marks of a Buddha. Typically buddha figures are facing forward, with a dot between the eyebrows, an ushnisha on the top of the head marked with a gold ornament, three lines under the neck, elongated earlobes, wearing the patchwork robes of a fully ordained monk and seated in the vajra posture with the right leg over the left. Buddhas can have different colours. Shakyamuni is generally depicted as golden in colour, Amitabha red, Medicine Buddha appears blue, etc.

In art Buddha Appearance refers to figures that have the form of a buddha as defined by the early Buddhist literature describing the characteristics of a buddha such as the Thirty-two Major and Eighty Minor Marks of a Buddha. Typically buddha figures are facing forward, with a dot between the eyebrows, an ushnisha on the top of the head marked with a gold ornament, three lines under the neck, elongated earlobes, wearing the patchwork robes of a fully ordained monk and seated in the vajra posture with the right leg over the left. Buddhas can have different colours. Shakyamuni is generally depicted as golden in colour, Amitabha red, Medicine Buddha appears blue, etc.

In Vajrayana Buddhism there are many Buddhas that do not have 'Buddha Appearance' but rather 'Peaceful Deity Appearance.' There are also a number of historical figures such as Nagarjuna, Garab Dorje and Sakya Pandita that can also have buddha-like characteristics. (See the Buddha Appearance Main Page).