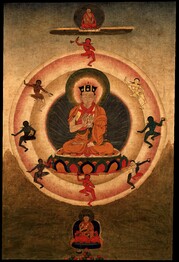

One of the first examples of Buddhist art in Tibet

was produced in the time of King Songtsen Gampo (Tt.: srong btsan agam po, reigned 608-649 A.D.), well before Buddhism was generally

known in the country. Songtsen Gampo married Nepalese and Chinese

princesses, both Buddhists. They each brought their family shrines

with them to Lhasa, the seat of the monarchy, and the king built

temples there to house them. These first landmarks of Buddhist art

survive until the present day. It was King Trisong Detsen (Tt.:

khri srong lde btsan), the great-grandson of Songtsen Gampo, who

invited to Tibet Padmasambhava (better known as Guru Rinpoche, “precious

guru”) and Santaraksita, the great spiritual masters who converted

the Tibetan people, learned and ordinary, and established Buddhism

as the national religion. These two also, with King Trisong Detsen

, founded Samye (Tt.: bsam yas) monastery, Tibet’s first,

which was to become the fundamental monument of Buddhism in that

country.

btsan agam po, reigned 608-649 A.D.), well before Buddhism was generally

known in the country. Songtsen Gampo married Nepalese and Chinese

princesses, both Buddhists. They each brought their family shrines

with them to Lhasa, the seat of the monarchy, and the king built

temples there to house them. These first landmarks of Buddhist art

survive until the present day. It was King Trisong Detsen (Tt.:

khri srong lde btsan), the great-grandson of Songtsen Gampo, who

invited to Tibet Padmasambhava (better known as Guru Rinpoche, “precious

guru”) and Santaraksita, the great spiritual masters who converted

the Tibetan people, learned and ordinary, and established Buddhism

as the national religion. These two also, with King Trisong Detsen

, founded Samye (Tt.: bsam yas) monastery, Tibet’s first,

which was to become the fundamental monument of Buddhism in that

country.

In the process of expanding his kingdom in the direction

of Persia, Trisong Detsen visited and sacked a religious establishment

there at a place called Batra. From there he brought back Persian

art and ritual objects as well as Persian master craftsmen. Along

with the objects came Pehar, the guardian spirit of the temple at

Batra. Pehar was tamed and converted by Guru Rinpoche and became

then the guardian deity of Samye.

Chinese influence also entered Tibet during this

period, especially in the form of Ch’an Buddhism, the Chinese

precursor of Zen. Eighty Ch’an masters came to teach in central

Tibet and attracted many Tibetan disciples. This strongly implanted

the influence of Chinese Buddhist ritual and generally provided

inspiration in the newly converted country.

The monasteries, which began to be built were modeled

on the palaces of Tibetan royalty. Even the interior designs and

seating arrangements were copied from the audience halls of Tibetan

kings. Iconographical subjects were painted on the walls as frescoes

and three-dimensional shrines were built and sculptured images of

deities placed upon them.

Thangkas or scrollpaintings were, from the first,

religious in nature. The first thangka originated in India and depicted

the Wheel of Life, a sort of diagram showing the world of samsara

and how to get out of it. Piligrams carried them on their backs

and unrolled them in village squares along their way for use in

illustrating their talks on the basic truths of Buddhism.

Thangkas

developed much wider use in Tibet, a country where for a long time

a large portion of the population was nomadic. In the nomadic Tibet,

it was the practice of local rulers to travel about their regions

setting up their princely camps in various places and holding court

in great, richly appointed tents. The Tibetan religious orders adopted

this pattern from them. Groups of monks moved over the country,

pitching camp in the highlands in summer and in the lowlands in

winter. The abbots, as they rode in caravans, went like kings, wearing

high gold hats of office and surrounded by attendants carrying banners.

The monks were great in numbers and carried with them everything

necessary for a full-scale religious establishment. According to

the Book of the Crystal Rosary, when the seventh Karmapa,

Chotrag Gyamtso (Tt.: chos grags rgyamtso, 1454-1506) traveled,

it required five hundred mules to carry the Kanjur (Tt.: bka; ‘gyur;

S.: Tripitaka) and other religious books. He was accompanied by

ten thousand monks with fifteen hundred tents. Portable shrines

were brought and full ritual paraphernalia, so that what amounted

to complete monasteries could be set up in the tents. Thangkas,

being portable, were used instead of frescoes. This nomadic monasticism

was a fundamental part of Tibetan spiritual life; one of the Tibetan

words for monastery, gar, in use of this day, means “camp.”

Thangkas

developed much wider use in Tibet, a country where for a long time

a large portion of the population was nomadic. In the nomadic Tibet,

it was the practice of local rulers to travel about their regions

setting up their princely camps in various places and holding court

in great, richly appointed tents. The Tibetan religious orders adopted

this pattern from them. Groups of monks moved over the country,

pitching camp in the highlands in summer and in the lowlands in

winter. The abbots, as they rode in caravans, went like kings, wearing

high gold hats of office and surrounded by attendants carrying banners.

The monks were great in numbers and carried with them everything

necessary for a full-scale religious establishment. According to

the Book of the Crystal Rosary, when the seventh Karmapa,

Chotrag Gyamtso (Tt.: chos grags rgyamtso, 1454-1506) traveled,

it required five hundred mules to carry the Kanjur (Tt.: bka; ‘gyur;

S.: Tripitaka) and other religious books. He was accompanied by

ten thousand monks with fifteen hundred tents. Portable shrines

were brought and full ritual paraphernalia, so that what amounted

to complete monasteries could be set up in the tents. Thangkas,

being portable, were used instead of frescoes. This nomadic monasticism

was a fundamental part of Tibetan spiritual life; one of the Tibetan

words for monastery, gar, in use of this day, means “camp.”

As the traveling monasteries were offered land and

forts by local kings and landowners, they hung their thangkas in

the shrine rooms of the permanent buildings. Ceilings and columns

were painted with decorative work. Manuscripts were illuminated.

Large mandalas were painted to place under the shrines. There were

also small card paintings to be used in rituals.

The word thangka comes from the Tibetan thang

yig, which mean “annal” or “written record.”

The ending yig, which means, “letter” and carries

the sense of “written,” is replaced by the ordinary

substantive ending ka. Thus the word thangka has the sense

of a record.

There are three predominant schools of Tibetan thangka

painting. The Kadam (Tt.: bka’ gdams), the early classical

school, shows simplicity, spaciousness and basic richness. Menri

(Tt.: sman ris) the later classical school originated in the fifteenth

century with an artist known as Menla Tondrup (Tt.: sman bla don

grub) from a family of great physicians. Its style maintains the

simplicity and spaciousness with a greater emphasis on richness

of detail, there being more Persian influence. New Menri (T.: Mensa;

Tt.: sman gsar), a later development of the Menri School in the

late seventeenth century, is quite, one mighty say, baroque and

overwhelmingly colorful, perhaps intimidatingly rich. There is a

great emphasis on curve at the expense of straight lines and very

little open space. The third main school, the Karma Gardri (Tt.:

Karma sgar bris) school was developed in the sixteenth century,

mainly by the eighth Karmapa, Mikyo Dorje (Tt.: Chos kyi ‘byung

gnas, 1700-1774). This style was further elaborated by the renowned

master Chokyi Jungne (Tt.: chos kyi ‘byuns gnas, 1700-1774),

the eighth Dai Situ (Th.: Ta’I Situ) and founder of Pepung

(Tt.: dpal’ spung) monastery, at a time when there was a general

renaissance in Tibetan Buddhism art, particularly in the area of

rupas (sculptured images). The Karma Gardri style is clear

and precise, spacious and, in places, rich. It shows marked Chinese

influence, evidenced by the use of pastel colors and prominent stylized

features of landscape.

The art of thangka was a family trade, passed on

from father to son in a long apprenticeship. When a thangka,  a

fresco or the embellishment of a monastery was commissioned, the

master was accompanied in the work by a group of students, including

his sons. The master ad his apprentices were welcomed with a feast

and there was a weekly feast for them as long as it took to complete

the work. They were presented with gifts at various times, usually

at the time of the feasts. They were paid in commodities, such as

cattle, quantities of butter, cheese, grain, jewelry, or clothes.

a

fresco or the embellishment of a monastery was commissioned, the

master was accompanied in the work by a group of students, including

his sons. The master ad his apprentices were welcomed with a feast

and there was a weekly feast for them as long as it took to complete

the work. They were presented with gifts at various times, usually

at the time of the feasts. They were paid in commodities, such as

cattle, quantities of butter, cheese, grain, jewelry, or clothes.

The traditional support for a thangka is white linen.

Silk was used on rare occasions. This cloth, the re shi

(Tt.: ras gzhi, “cloth background”), is stretched on

a wooden frame. It is then prepared with a base of chalk mixed with

gum Arabic. The first step is a freehand charcoal sketch by the

master. The charcoal is made by baking wood

of tamarisk in a metal tube. The master then goes over the sketch

in black ink and marks the various areas according to the colors

that are to be put in by the apprentices.

Traditionally, blue is made from ground lapis lazuli,

red is vermilion from cinnabar; yellow is made from sulphur, green

from tailor’s greenstone. Pink is made from flower petals

and, more recently, also from cosmetics imported from China or India.

To make a brush, the tip of a stick, usually tamarisk

or bamboo, is dipped in glue. The artist carefully places the

hairs, one by one. Best is the hair of the sable or of a small Himalayan

wildcat called sa (Tt.: gsa’). Ideally, the hair should be

pulled from the tail of a live animal, since thus it remains more

resilient. The hairs having been placed on the stick, they are bound

by a silk thread, also dipped in glue.

When the basic colors are filled in by the apprentices,

the master goes over the work, shading with lighter colors derived

from flowers and vegetables. Finally he retouches with gold. An

apprentice burnishes the gold with a roundpointed instrument made

from an agate.

Traditionally, the eyes of the deities were left

for the last so they cold be painted in at a special celebration

called “opening the eyes.”

When the painting is completed it is mounted on

cloth. Originally there were two borders, one of red brocade, one

of blue. Later yellow brocade also became acceptable and the modern

style has three brocade borders, yellow, red and blue. In the center

of the borders below the painting is placed a square of particularly

elaborate brocade, which is known as the “door.” In

some sense the brocade borders represent an edifice, which houses

the world of the painting. The “door” provides an entrance

into that world.

The thangkas are covered for protection with red

and yellow silk veils, red and yellow being the colors used for

the clothing of the sangha (community of the dharma). Two red ribbons

hang over the veils. These are known as lung non (Tt.:

rlung gnon), “wind holders.” These ribbons hark back

to the time when thangkas were hung in tents and wind required them

to be tied against the wall. The rolling sticks at the bottom of

the brocade are finished with gold or silver knobs.

Occasionally

thangkas were done in silk appliqué or embroidered on silk.

Occasionally

thangkas were done in silk appliqué or embroidered on silk.

Sculptured images in the traditional manner are

first modeled in sealing wax (T.: be; Tt.: ‘bes). Clay is

molded onto a wax image and the wax melted away. The metal cast

in the clay molds is usually pure copper. Very old images are found

to have been cast in bell metal, a mixture of copper, silver and

pewterlike alloys. Once cast, the images are gilded. Then they are

often highlighted with painted colors. Ornaments are sometimes inlaid

with jewels and, quite frequently, the hair, lips and eyes are touched

with color. There is a special “opening of the eyes”

ceremony, just as with thangkas, when the eyes are painted in. The

images are hollow and after the “eye-opening” they are

consecrated in a ceremony, which involves filling them with relics

and mantras. Before the bottom is sealed, as the very last thing,

grains of precious stones are put into the image to add a sense

of basic richness. It is on account of this practice that images

have frequently been broken into by those hoping to find valuable

gems.

As a social phenomenon, making images was much the

same as thangka painting. The art and lore were passed down in families

and through apprenticeship. A sculptor and his apprentices having

come to a monastery to provide it with a new treasure, were feted,

given gifts and paid just as were the thangka painters.

It is widely thought that thangka painting is a

form of meditation. This is not true. Though all the thangkas have

religious subjects, most of the artists were and are lay people.

As has been said, the art is passes down in families. It is true

that a master thangka painter has knowledge of iconographical detail

that might easily awe a novice monk. Naturally, also, artists have

a sense of reverence for the sacredness of their work. Nevertheless,

the painting of thangkas is primarily a craft rather than a religious

exercise. One exception is the nyin thang (“one-day

thangka”) practice in which, as part of a particular sadhana,

while repeating the appropriate mantra, uninterruptedly, without

sleeping, a monk paints a thangka in one twenty-four hour period.

Thangkas were painted on commission for noteworthy

social occasions; for the welfare of a newly born infant, for the

liberation of one just dead, at the commencement of some new project.

Often artistically inclined gurus or abbots painted thangkas to

glorify their lineages or convey the richness or inspiration of

their tradition.

Thangkas are used as objects of adoration, but mainly

as a means to refine a meditative visualization. They are displayed

over shrines which are bedecked with butter lamps, incense and offerings

and ritual objects of many kinds. Thangkas of the lives of saints

are displayed for the celebrations of holidays associated with them.

Special thangkas painted by great teachers of particular lineages

are also hung for yearly ceremonies. Practitioners hang the thangkas

of their yidams or gurus over the shrines in their rooms as constant

reminders of their presence. Formal rooms were hung with thangkas

in Tibet to receive important guests such as kings, government officials

or eminent spiritual teachers. Sometimes thangkas hung in the audience

halls of local rulers.