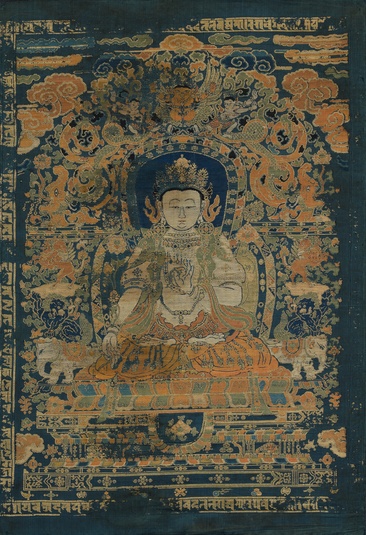

Item: Avalokiteshvara (Bodhisattva & Buddhist Deity) - Bodhisattva

| Origin Location | China |

|---|---|

| Date Range | 1400 - 1499 |

| Lineages | Buddhist |

| Material | Ground: Textile Image, Brocade |

| Collection | Private |

Alternate Names: Lokeshvara Avalokita Lokanata Lokanatha Mahakarunika

Classification: Deity

Appearance: Peaceful

Gender: Male

Avalokiteshvara: An Early Ming Textile

Avalokiteshvara is depicted seated in vajra posture, with the right hand performing the gesture of supreme generosity and the left hand in a gesture of blessing. The two hands hold lotus flower stems that bloom at the shoulders. Depicted as a youthful prince of sixteen years of age, he is adorned with a long green scarf draped over his shoulders and arms with an orange silk skirt secured by a belt of colorful jeweled ornaments at the hips. Seated atop a multi-tiered lotus throne, surrounded by a floral frame incorporating various auspicious mythical creatures such as white elephants, lions, qilins, kinnaras, and makaras, finally with two apsara-like figures flanking a garuda at the top, beneath multi-colored clouds of various shapes. The artwork was originally framed on the four sides by a Lantsa script inscription done in gold. The textile is finely woven with rich shades of orange, yellow, green, and light blue, with outlines in gold against a deep cobalt blue.

The identification of this figure as Avalokiteshvara was made based on similar sculptural examples of the deity along with the exclusion of attributes belonging to other possible figures such as Maitreya, Manjushri, or Vajrapani. With a lack of inscriptions, apart from the Lantsa text framing the composition, and a lack of iconographic attributes, the identification is slightly challenging but generally accepted to be a form of Avalokiteshvara, a narrative figure belonging to the Sutra tradition of Mahayana Buddhism. As shown in Heavens’ Embroidered Cloths: One Thousand Years of Chinese Textiles, Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong, 1995, cat. nos 28, 29 and 30, there are at least three other examples of this same work all created in the same textile workshop. A fifth work depicts Vairochana Buddha, framed with the same floral and decorative background along with the same Lantsa inscription border. Another identical example, with an RCD Radio Carbon Dating test number RCD-6767 consistent with the dating, is now in the collection of the Zhiguan Museum of Art, published https://www.himalayanart.org/items/23544.

According to the scholar John Vollmer, https://www.himalayanart.org/items/23544, in addition to the Zhiguan Museum example there are three other examples of this design known: one in the collection of the Hong Kong Museum of Art and two in the Chris Hall Collection Trust. He also notes how numerous inaccuracies can be found in Buddhist designs woven in China during the 13th and early 14th centuries. In earlier times, these depictions were either painted or printed. When they transitioned to textile art, those unfamiliar with Buddhist iconography might not have easily identified the specific characteristics that were obvious to those well-educated in the field. It's believed that some of the artisans producing these intricate textiles were Muslims who could trace their lineage back to skilled weavers who were forcibly moved from their Muslim regions of western Central Asia by the Yuan dynasty rulers. Some of these artisans who later settled in places like Beijing and Sichuan might have retained their Muslim faith, and thus produce art with inaccuracies in iconography. This could explain the production challenges that occurred with some of the other textiles with the same design. This textile, woven correctly, used a lavish amount of gold and the complex weaving indicates the product to originate from an imperial workshop, most likely made as a gift to a noble in Tibet. The technical challenges did not disappear until the period of the Yongle Emperor, a fanatical Buddhist, demanded perfection from the imperial weaving ateliers. Stylistically, the throne is done in the Yongle style that can be found on a piece like the famous Yongle bronze guild Shakyamuni from the British Museum Collection. Considering the historical information and technical/stylistic features of the textile, we can establish that this work is from the late 14th to early 15th century. (Sotheby's acknowledges and thanks Shinzo Shiratori for preparing this catalogue note).

Shinzo Shiratori, 8-2023

Textile: Early Ming Woven Set

Buddhist Deity: Avalokiteshvara Main Page

Buddhist Deity: Avalokiteshvara (Vajra Posture Sculpture)

Collection: Sotheby's New York (Painting, September 2023)