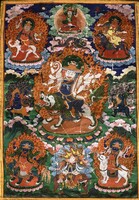

Drala Yesi Gyalpo: a worldly protector. The founder of the Bon Religion, Tonpa Shenrab, sits above and various human, daemon-like and animal figures encircle the central protector.

Drala Yesi Gyalpo: a worldly protector. The founder of the Bon Religion, Tonpa Shenrab, sits above and various human, daemon-like and animal figures encircle the central protector.

Dressed as a warrior (Drala Appearance) with chain mail and a helmet, Drala Yesi Gyalpo holds upraised in the right hand a riding crop and the left held at the side firmly grasps upright a long spear decorated with a pendant. A sword, bow and quiver of arrows hang at the waist. Atop a galloping white horse he is surrounded by billowing white clouds and wild animals.

At the upper corners, sides and along the bottom are numerous animals, attendants mounted on various animals and warriors riding horses. Each figure is accompanied by a Tibetan name inscription.

There are three groups of figures that surround the central deity.

The first group of four figures are found at the top and bottom corners. They each have an animal face and ride the same animal as represented by the face of the rider. At the top left is Dudul Kyung Chen with a Kyung (bird) face riding a kyung. At the top right is Kundul Drag Chen with a dragon face riding a dragon. At the bottom right is Pa-ngam Darchen with a tiger face and riding a tiger. At the bottom left is Kadrag Dradul with a lion face and riding atop a lion.

The second group, below the central figure, consists of four human-like warriors in Drala Appearance riding horses. At the center of this group is Domgo Lang Nying, a Kyung faced figure with bird wings, also riding a horse.

The third and last group consists of various animals, birds and four legged creatures, eleven in number, surrounding the central figure and interspersed with the other two groups. Some of the animals are easily recognizable such as the golden-eyed kyung, the black kyung, pheasant, wolf (?), tiger, leopard, conch lion, snow lion, golden lion, flying mouse and marmot (?). These eleven animals appear very similar in function to the Thirteen Werma that accompany Ling Gesar when he appears in the Gesar Norbu Dradul form.

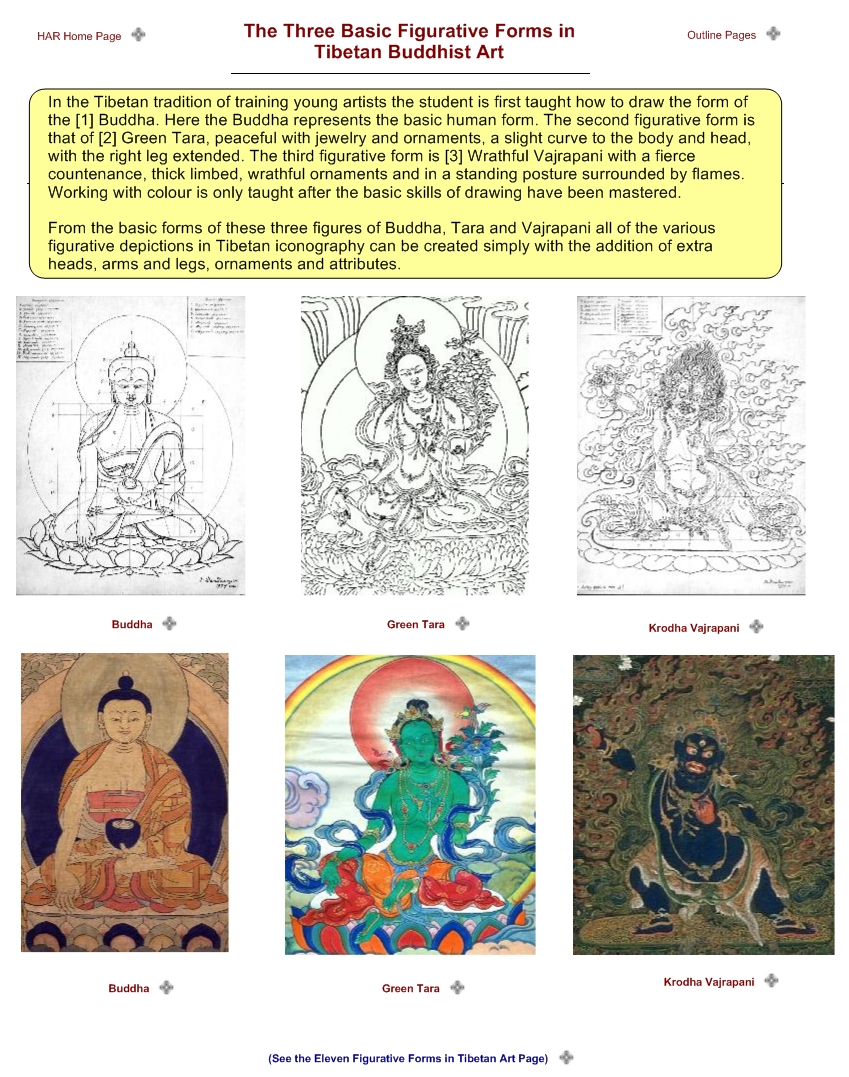

In the Tibetan tradition of training young artists there are three basic figurative forms that must be learned. The student is first taught how to draw the form of the [1] Buddha. Here the Buddha represents the basic human form. The second figurative form is that of [2] Green Tara, peaceful with jewelry and ornaments, a slight curve to the body and head, with the right leg extended. The third figurative form is [3] Wrathful Vajrapani with a fierce countenance, thick limbed, adorned with wrathful ornaments, or a combination of peaceful and wrathful, and in a standing posture surrounded by flames. Working with colour is only taught after the basic skills of drawing have been mastered.

In the Tibetan tradition of training young artists there are three basic figurative forms that must be learned. The student is first taught how to draw the form of the [1] Buddha. Here the Buddha represents the basic human form. The second figurative form is that of [2] Green Tara, peaceful with jewelry and ornaments, a slight curve to the body and head, with the right leg extended. The third figurative form is [3] Wrathful Vajrapani with a fierce countenance, thick limbed, adorned with wrathful ornaments, or a combination of peaceful and wrathful, and in a standing posture surrounded by flames. Working with colour is only taught after the basic skills of drawing have been mastered.

It has been very difficult to track down the earliest painted images or sculpture of

It has been very difficult to track down the earliest painted images or sculpture of

Many have heard of the famous black hat of the Karmapa and the red hat of the Shamarpa, maybe the lotus hat of Padmasambhava and the yellow hat of the Gelugpa Tradition. What about a white hat that is identical to the black hat of Gyalwa Karmapa?

Many have heard of the famous black hat of the Karmapa and the red hat of the Shamarpa, maybe the lotus hat of Padmasambhava and the yellow hat of the Gelugpa Tradition. What about a white hat that is identical to the black hat of Gyalwa Karmapa?