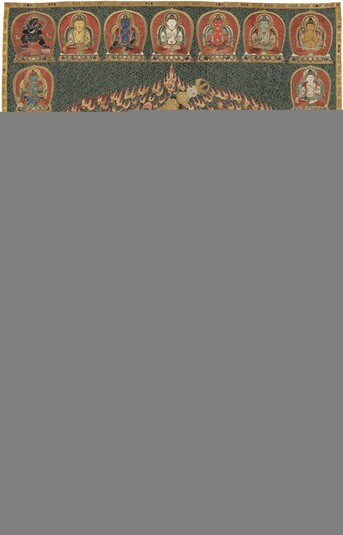

Item: Yamari, Rakta (Buddhist Deity) - Heruka

| Origin Location | China |

|---|---|

| Date Range | 1400 - 1499 |

| Lineages | Sakya, Gelug and Buddhist |

| Size | 335.28x213.36cm (132x84in) |

| Material | Ground: Textile Image, Embroidery |

| Collection | Private |

Classification: Deity

Appearance: Wrathful

Gender: Male

Rakta Yamari (Tibetan: shin je she mar. English: the Red Enemy of Death): a meditational form of the deity Manjushri. This composition was made either as a set or a series of works created in the workshops of the Yongle Emperor most likely between 1416 and 1418. The other known works from the same time and atelier are a Chakrasamvara, Vajrabhairava and Panjara Mahakala. (See Yongle Textile Workshop discussion and publication).

(See the Rakta Yamari Main Page and Outline Page).

Sanskrit: Rakta Yamari Tibetan: Shin je she mar

Tibetan: Shin je she mar

Rakta Yamari is a Tantric Buddhist meditational deity believed to be an emanation of the deity and bodhisattva Manjushri. There are two general types of Yamari deities - red (rakta) and black (krishna). The Red (rakta) Yamari has several different traditions - each primarily differentiated by the number of deities represented in the mandala and the associated human lineage teachers. The Krishna and Rakta Yamari figures belong to the New 'Sarma' Tradition of Tibetan Buddhism and are practiced in all of the main schools. Manjushri has a number of popular meditational forms belonging to the Anuttarayoga Classs of Tantric Buddhism which are primarily the Manjuvajra Guhyasamaja, Vajrabhairava, and the two Yamari - red and black. Manjushri also has dozens of peaceful meditation forms originating in the Kriya, Charya and Yoga Tantras.

Rakta Yamari Lineage, Thirteen Deity Mandala and Abhisheka: Bhagavan Yamari, Acharya Brahmin Paldzin, Virupa, Dombi Heruka, Biratipa, Gambhiramati, Nishkalamka, Deva Revandra, Prabhawa, Lama Gewai Shenyen Dorje Dzinpa Chenpo Lowo Lotsawa, Lama Chokyi Gyalpo.

Rakta Yamari Lineage, Five Deity Mandala, Abhisheka and Sadhana together with its Branches: Manjushri Yamari, Jnana Dakini, Acharya Virupa, Dombipa, Baritipa, Mati Garbha, Gambhira Mati, Nishkalamke Devi, Chal Lotsawa, Lord of Yoga Gvalo, Lama Chokyi Gyalpo (Chogyal Pagpa 1235-1280).

Jeff Watt 4-2013

![]() Rakta Yamari: An Introduction

Rakta Yamari: An Introduction

by Jeff Watt (10-2014) (Chinese Language Translation)

Rakta Yamari is a Meditational deity that belongs to the Vajrayana Tradition of Mahayana Buddhism. Vajrayana is based on the Tantra literature of India. A meditational deity is not necessarily a real entity, person or god. Within Vajrayana Buddhism, in most cases, a deity is a construct, an invention, a created object for meditation. Symbolism plays an important role and each meditational deity is associated with a specific metaphor. The metaphor for Rakta Yamari is 'death.' The name means the 'Red Killer of Death.' In this symbolic meaning the idea of death refers directly to the suffering and unhappiness in the world as described in Buddhist philosophy. The general appearance of the deity, number of faces, arms, ornaments, decorations and attributes are all part of a mnemonic device (memory system) that incorporates the most essential of Buddhist principles and core teachings into a single object. The Indian source text for the teachings of Yamari is the Rakta Yamari Tantra Raja Nama (raktayamari-tantraraja-nama. gshin rje'i gshed dmar po zhes bya ba'i rgyud kyi rgyal po [TBRC w25383]). The original text has nineteen chapters. In the 14th century a second Indian text with twenty-two chapters appeared in Tibet in the possession of a scholar named Kunpang Chodrag Pal Zangpo. This version of the text was taught to the great abbot of Shalu Monastery Buton Rinchen Drub (1290-1364). Both texts still exist today and both are considered authoritative.

Rakta Yamari is grouped within a larger set of three deities in total. The other two are Vajrabhairava and Krishna Yamari. All three employ the metaphor of death and are linked to the bodhisattva Manjushri - a figure originally popularized in the Mahayana Sutras. The origin of Rakta Yamari is shrouded. There does not appear to be any origin myth in the source literature. Possibly there will be secondary Sanskrit literature that will offer more information in the future. Late Tibetan sources, such as Jamgon Amezhab (1597-1659) state that Rakta Yamari was an emanation body created by Shakyamuni Buddha for subduing the Four Maras during an episode from the Buddha's own life story. The Buddha then entrusted the practices to the bodhisattva Vajrapani. This information can be found in the 'History of the Two Yamaris and Bhairava' by Jamgon Amezhab.

The Rakta form of Yamari was the last of the three Yamari/Bhairava meditational deities to arrive in the Himalayan regions in approximately the 13th century. From the Indian tradition there were a number of well known teachers associated with the red form of Yamari. The most prominent were the mahasiddhas Shridhara, Virupa and Dombi Heruka. The siddhas are difficult to date but are generally placed somewhere between the 8th and 9th centuries. Subsequent to that, several famous Tibetan translators were responsible for introducing the practice of Rakta Yamari to Tibet. Chag Lotsawa (1197-1264, chag lo tsA ba chos rje dpal), a colleague of Sakya Pandita Kunga Gyaltsen (1182-1251), translated a number of important Indian Sanskrit texts on Yamari into Tibetan. He was also the principal translator for the Vajravali cycle of mandalas composed by the Indian scholar Abhayakara Gupta (d.1125). This latter text, a compendium of practices, was important because it also contained a very popular version of the Rakta Yamari with a description of the mandala and initiation ritual.

Within the tradition of Tibetan Buddhism the lineages of teachers extending back to India were always considered of paramount importance because they directly indicate legitimacy, orthodoxy and authority. However, after reviewing over a dozen different lineages of teachers of the Rakta Yamari tradition it appears that there were many inconsistencies with the chronology as well as the spellings for names. It seems likely that there were also confusions between the Sanskrit and Prakrit language spellings leading to mistaken attributions. It is probably best to look on the traditional lineages of teachers as suggestions rather than definitive and final. Two examples of the Rakta Yamari lineage are given below:

Rakta Yamari Thirteen Deity Mandala Lineage: Bhagavan Yamari, Acharya Brahmin Paldzin, Virupa, Dombi Heruka, Biratipa, Gambhiramati, Nishkalamka, Deva Revandra, Prabhawa, Lama Gewai Shenyen, Dorje Dzinpa Chenpo, Lowo Lotsawa, Lama Chokyi Gyalpo, etc.

Rakta Yamari Five Deity Mandala Lineage: Manjushri Yamari, Jnana Dakini, Acharya Virupa, Dombipa, Baritipa, Mati Garbha, Gambhira Mati, Nishkalamke Devi, Chal Lotsawa, Lord of Yoga Gvalo, Lama Chokyi Gyalpo (Chogyal Pagpa 1235-1280), etc.

Chogyal Pagpa Lodro Gyaltsen (1235-1280), a student of both Sakya Pandita and Chag Lotsawa, popularized the practice of Rakta Yamari at the Mongolian court of Kublai Khan during the Yuan period. He wrote a number of Yamari meditation practice manuals for Mongolian princes giving both the names and the date of authorship in each colophon. Following that, less than fifty years later the abbot of Shalu Buton Rinchen Drub granted the initiation of Rakta Yamari to Lama Dampa Sonam Gyaltsen (1312-1375), a great nephew of Chogyal Pagpa. Sonam Gyaltsen in turn passed it on to an abbot of Nartang Monastery. From there the initiation was given to Je Tsongkapa Lobzang Dragpa (1357-1419) the founder of the Gelug Tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. From Tsongkapa a great number of teachings and initiations were passed down to Jamchen Choje Shakya Yeshe (1354-1435), a principal student, and later the founder of Sera Monastery in 1419.

In the early 1400s the Yongle Emperor sent many letters to Je Tsongkapa inviting him to China. Tsongkapa always declined but finally agreed to send in his place the eminent scholar Jamchen Choje Shakya Yeshe. In 1414 Shakya Yeshe arrived at the court of the emperor. Shakya Yeshe remained in China until 1418 teaching all manner of Buddhist subjects and bestowing many types of Tantric initiation. The Yongle emperor was not exclusive but rather eclectic when inviting religious teachers. He enjoyed the company of notables such as the 5th Karmapa Deshin Shegpa and the Sakya Trizin - throne holder of Sakya. Gifts were always exchanged between the emperor and his guests and many examples from centuries past can still be seen both in Tibet and China today. The finest examples of those gifts have generally been sculpture metal work and textile hangings, either embroidery or loom woven textiles. The Rakta Yamari embroidered textile displayed here is a fine example of both art and religious iconography. The majority of the work is true to the textual descriptions found in the classic sources. Some small details have been re-interpreted by the master artist for the sake of appearance or colour compatibility.

At the center of the composition is Rakta Yamari. He is described in ritual texts as "... Bhagavan Krodha Yamari with a body red in colour, one face and two hands. The right hand holds aloft a white stick marked with a fresh yellow head. The left holds a blood filled skullcup embracing the Vidya of natural light [the consort Vajra Vetali]; mouth with bared fangs and tongue curled, possessing three round red eyes, yellow moustache, eyebrows and hair flowing upward, wearing a lower garment of tiger skin, adorned with the eight great nagas and a necklace of half a hundred dripping heads and a crown of five dry skulls. Frightful with the resources of a 'yamari' standing above a red buffalo in a manner with the right leg bent and left straight in the middle of a blazing fire of pristine awareness." (Composed by Thartse Panchen Namka Palzang, 18th century).

The traditional description is quite brief and falls short of describing some of the more obvious and interesting subtle elements of the Rakta Yamari image. Slightly above the crown of the head is a very small depiction of the Buddha Vajrasattva, white in colour, holding a vajra sceptre to the heart with the right hand and a bell at the hip with the left. Held upraised in the right hand is an eight sided staff decorated with a freshly severed head, a decomposing head and a white skull. The staff is adorned at the top and bottom with a half vajra sceptre symbol. Eight types of snakes adorn the body from the top of the head to the ears, long necklace, short necklace, belt, armlets, bracelets and anklets. Under the feet of Yamari is the blue coloured body of Yama, the Lord of Death. He holds a staff in the right hand and a lasso in the left. Very few of the Sanskrit and Tibetan texts describe the form of Yama under the feet of Yamari. It is however relatively common in painting and sculpture.

The entire form of Yamari, along with all of the attributes, are understood as both an object of meditation and as a mnemonic device. The one face represents the embodiment of the wisdom of all Buddhas as having one taste, or flavour, ultimate truth. The red body colour represents the desire to overcome all maras and place all beings in the state of enlightenment. The staff subdues the afflictions, maras. The left hand holds a skullcup containing the essence of the four maras transformed. The four bared fangs are fearlessness over the four maras - the causes for delaying enlightenment: klesha mara, skandha mara, devaputra mara and mrtya mara. The three round eyes express compassion for all beings in the three times of past, present and future as well as the three watches of the day and three watches of the night. The orange and red hair is to symbolize the increasing qualities of the Buddha and the aspects of the Five Paths of Seeing, Meditation, etc. (the Mahayana Five Paths). The crown of five dry skulls symbolizes the five poisons transformed into the five wisdoms. The necklace of fifty fresh heads represents the vowels and consonants of the Sanskrit language. The eight snakes represent the Eight Great Nagas: Vasuki, Hulunta, Padma, Mahapadma, Karkota, Kulika, Takshaka and Shankhapala. They represent the subjugation of various obstacles and the accomplishment of skillful activities. The lower garment of tiger skin gives fright to those with a violent disposition. The right leg bent represents the true nature of reality. The left straight represents compassion for all beings. The flat sun and moon discs under the reclining buffalo represent the wishing and entering enlightenment thoughts. The surrounding fire represents a non-conceptual wisdom arising from a mind of pristine awareness. Every aspect of the form of Yamari and the consort Vajra Vetali have symbolic and coded meaning.

Based on the iconography alone, it is not possible to identify this figure of Yamari with a particular mandala configuration or Tibetan lineage tradition. There are four principal ways that Yamari appears in art and is practised as a meditation or ritual. The first form has Yamari embracing the consort without any attendants or other deities in the mandala arrangement. The second is Yamari and consort with four surrounding deities embracing a consort. There are actually ten deities in total but they are always referred to as a five deity mandala. Following that, there is a nine and a thirteen deity mandala.

In the top register of the Yamari textile there are seven figures. At the far left side is Heruka Vajrabhairava with one face and two hands. He is male and has a buffalo head with two horns and a gaping mouth. In the proper right and left hands he holds a curved flaying knife and a skullcup, standing atop a buffalo. Proceeding from left to right the next five figures are the Five Symbolic Buddhas of Tantric Buddhism: yellow Ratnasambhava, blue Akshobhya, white Vairochana, red Amitabha and green Amoghasiddhi. Aside from the body colours and hand gestures they all appear identical in ornamentation and posture. At the far right side is the bodhisattva Manjushri with one face and two hands, orange in colour, performing the gesture of teaching. Manjushri also holds with the fingers the stems of two flower blossoms that support the two attributes of a sword and book.

Below the row of figures in the register on the left side is the figure of the female Buddha known as Tara, green in colour, with one face and two hands, seated in a relaxed posture. On the right side is a similar figure, white in colour, with the legs folded in the vajra posture. The hand gestures and attributes are the same as the Tara on the left side of the composition. In all likelihood, this is White Tara, another form of the deity used specifically for longevity rituals. The identification for this figure is not completely certain as there are missing attributes that are common for White Tara but missing from this depiction.

Along the bottom of the composition are seven dancing female figures each holding aloft a specific offering substance. The seven are the more commonly known of the Eight Offering Goddesses. Starting from the left is white Arghuam, green Padya, white Pushpe, blue Dupe, red Aloke, green Gandhe, and yellow Naivedye. The substances they hold are a white conch with water for drinking, again a white conch with water for washing, a bowl of flowers, a bowl of incense, a lamp with flickering flames, a white conch with scented water and finally a bowl of food (peaches). The eighth and final (omitted) offering goddess would be Shapda and she typically holds a musical instrument. Each of the goddesses hold their own offering up with one hand while performing a dance gesture with the other hand, all the while standing in a dance posture with either the right or left leg raised.

The textile of Yamari follows very closely in style and size to three other known works, two in Tibet and one in a private collection. All four works appear to be from the same Imperial workshop and the same time period. The top registers for two of the other textiles are slightly different in number and size of figures. The lower registers of each are almost identical between the four. The central subjects of the other three works are Vajrabhairava, Chakrasamvara and Panjarnatha Mahakala. Based on composition and uniformity the Rakta Yamari under discussion and the Chakrasamvara are the closest in style and iconographic program. The two might have even constituted part of a set of compositions. The Vajrabhairava follows next in uniformity although having a top register with many more figures than the Yamari and Chakrasamvara examples. The Vajrabhairava composition follows completely a Gelug iconographic program that is not followed by the Sakya or Kagyu Traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. The Panjarnatha Mahakala textile follows a uniquely Sakya iconograhic program. Based on this brief analysis and the textual documentation of important religious visitors from Tibet to the the Imperial court, it is most probable that the first three textiles were created as gifts for the Gelug Scholar Shakya Yeshe and the Mahakala textile for a religious dignitary of the Sakya Tradition.

------------------------------------------------------------

Amezhab, Jamgon. dpal gshin rje gshed dmar nag 'jigs gsum gyi dam pa'i chos byung ba'i tshul legs par bshad pa zab yangs chos sgo 'byed pa'i rin po che'i lde mig dgos 'dod kun 'byung zhes bya ba bzhugs so.

Henss, Michael. 'The Woven Image: Tibeto-Chinese Textile Thangkas of the Yuan and Early Ming Dynatsie. Orientations, November 1997.

Himalayan Art Resources. Rakta Yamari Main Page. https://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=349. Jeff Watt, 2-2005.

Rakta Yamari Textile. Himalayan Art Resources. HAR #57041. https://www.himalayanart.org/image.cfm/57041.html.

Yongle Textile Workshop: A Discussion. https://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=3840

raktayamari-tantraraja-nama. gshin rje'i gshed dmar po zhes bya ba'i rgyud kyi rgyal po [TBRC w25383, w25384].

Reynolds, Valrae, 'Buddhist Silk Textiles: Evidence for Patronage and Ritual Practice in China and Tibet.' Orientations, April 1997.

Roerich, George, trans. 1959. Biography of Dharmasvamin, A Tibetan Monk Pilgrim. Patna: K.P. Jayaswal Research Institute.

Roerich, George, trans. 1996. The Blue Annals. 2nd ed. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas.

Textile: Woven Artwork Main Page

Buddhist Deity: Manjushri (Highest Yoga Tantra)

Textile: Masterworks (纺织品, འཐག་དྲུབ་མ།)

Buddhist Deity: Yamari, Rakta (Iconography & Religious Context)

Collection: Private 1

Buddhist Deity: Yamari, Rakta, Main Page

Textile: Main Page

Buddhist Deity: Yamari, Rakta (Masterworks)

Buddhist Deity: Yamari, Rakta (with corpse)

Textile Set: Yongle Workshop

Subject: Yongle Textile Workshop Discussion (Chinese Translation)

Subject: Yongle Brocade Textiles

Subject: Yongle Textile Workshop Discussion

Buddhist Deity: Yamari Main Page