This image is of the earliest known Karma Kagyu Refuge Field painting - Field of Accumulation - to appear in any museum or private collection (or known mural in situ). It can be dated to the life of the 15th Karmapa Kakyab Dorje (1870/71-1921/22). His typical iconographic attributes are a vajra and bell held in the hands along with two flowers supporting a sword and book. In this painting the 15th Karmapa is depicted in the lower part of the composition. Above his left shoulder is a long-life vase on a flower blossom with the sword and book on a flower at the right shoulder. The vase or rather a long-life vase is often used to indicate that a teacher is still alive when a painting or sculpture is commissioned. It is an auspicious long-life gesture by the donor and artist. At the right and left sides of the seated Karmapa are Situpa and Jamyang Dorje. The Situ must be the 11th Situpa, Pema Wangchug Gyalpo (1886-1952). The other figure of Jamyang Dorje is not quite as identifiable but is likely to be Jamyang Rinpoche the 11th Shamarpa and son of the 15th Karmapa, Kakyab Dorje.

This image is of the earliest known Karma Kagyu Refuge Field painting - Field of Accumulation - to appear in any museum or private collection (or known mural in situ). It can be dated to the life of the 15th Karmapa Kakyab Dorje (1870/71-1921/22). His typical iconographic attributes are a vajra and bell held in the hands along with two flowers supporting a sword and book. In this painting the 15th Karmapa is depicted in the lower part of the composition. Above his left shoulder is a long-life vase on a flower blossom with the sword and book on a flower at the right shoulder. The vase or rather a long-life vase is often used to indicate that a teacher is still alive when a painting or sculpture is commissioned. It is an auspicious long-life gesture by the donor and artist. At the right and left sides of the seated Karmapa are Situpa and Jamyang Dorje. The Situ must be the 11th Situpa, Pema Wangchug Gyalpo (1886-1952). The other figure of Jamyang Dorje is not quite as identifiable but is likely to be Jamyang Rinpoche the 11th Shamarpa and son of the 15th Karmapa, Kakyab Dorje.

The painting is extremely detailed and each figure is accompanied by a written name inscription beneath. The specific Karma Kagyu teachers depicted are of the Mahamudra lineage beginning with Vajradhara, the primordial Buddha, and the Indian mahasiddha Saraha. The over-all appearance of the composition along with the names of the teachers follows closely the text Ngedon Dronme of Jamgon Kongtrul (1813-1899) based on the Ngedon Gyatso of the 9th Karmapa, Wangchug Dorje, (1555-1603). Kongtrul is also depicted in the composition slightly to the upper left of Kakyab Dorje (the viewer's right).

This type of painted composition, based on the visual examples in the HAR database, appears to be a very late phenomenon in Tibetan and Himalayan art quite possibly only becoming popular in the 18th century. The earliest examples appear to be the Gelug paintings of the late 18th century based on the liturgical text of the 'Lama Chopa' written by the 1st Panchen Lama, Lobzang Chokyi Gyaltsen (1570-1662) in the 17th century.

Nyimgma Refuge Field paintings first appear in the 19th century as a visual representation of the Field of Accumulation for the Longchen Nyingtig uncommon preliminary practices as taught by Jigme Lingpa and later explained in detail by Patrul Rinpoche in the famous text, The Words of My Perfect Teacher. These Longchen Nyingtig refuge depictions are the only Nyingma paintings identified so far.

As for the Kagyu Tradition the Drigung appear to be the earliest to adopt this visual model with a number of examples followed by the Drugpa Kagyu with one example on the HAR website. The Karma Kagyu and Sakya Traditions are the last to adopt the visual form with one example each represented on HAR. The earliest Karma Kagyu Refuge Field is dated to between 1900 and 1922 based on inscriptions and the figure of the 15th Karmapa, Kakyab Dorje. The earliest Sakya artifact is a block print image of a White Tara Field of Accumulation from the Dege Parkang (Printing House) in East Tibet, likely a creation of the 20th century.

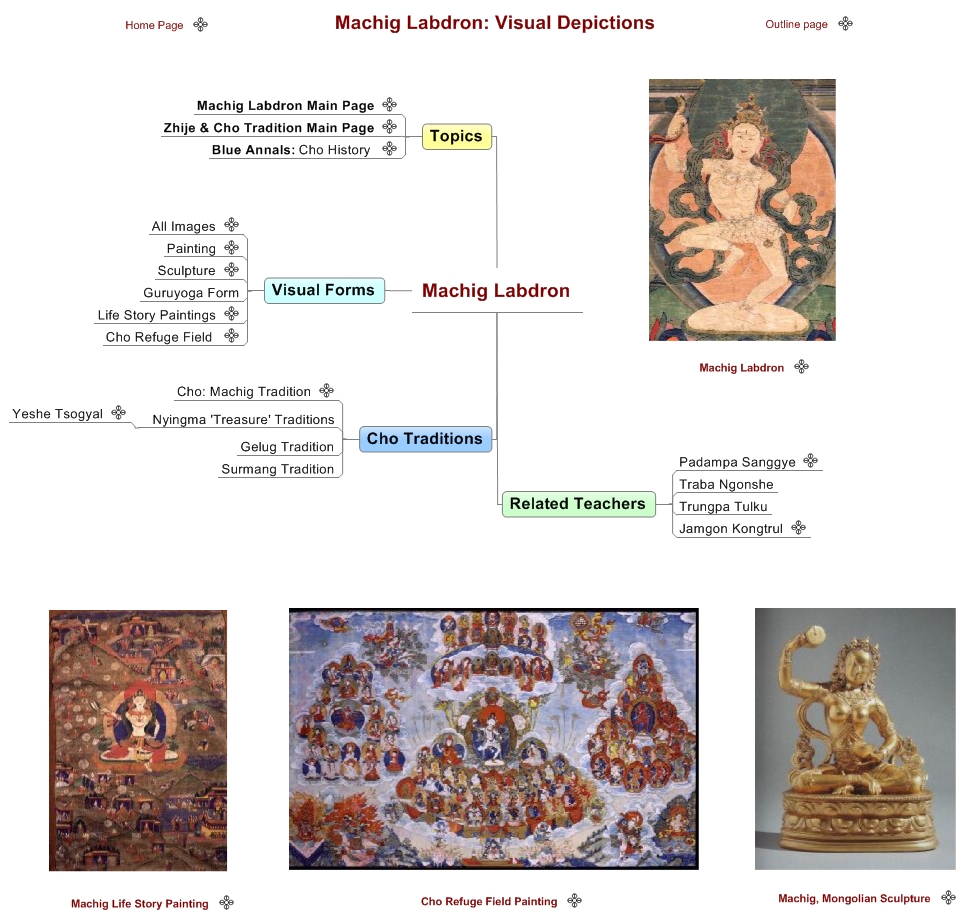

The pages relating to Cho (Chod) have been updated with new images and sections. A new Machig Labdron Outline Page has been added along with updates to the Cho Refuge Field Page and the Religious Tradition Page. The Blue Annals Cho History still requires editing, formatting and the addition of images.

The pages relating to Cho (Chod) have been updated with new images and sections. A new Machig Labdron Outline Page has been added along with updates to the Cho Refuge Field Page and the Religious Tradition Page. The Blue Annals Cho History still requires editing, formatting and the addition of images.